Head-marking language

A language is head-marking if the grammatical marks showing agreement between different words of a phrase tend to be placed on the heads (or nuclei) of phrases, rather than on the modifiers or dependents. Many languages employ both head-marking and dependent-marking, and some languages double up and are thus double-marking. The concept of head/dependent-marking was proposed by Johanna Nichols in 1986 and has come to be widely used as a basic category in linguistic typology.[1]

In English

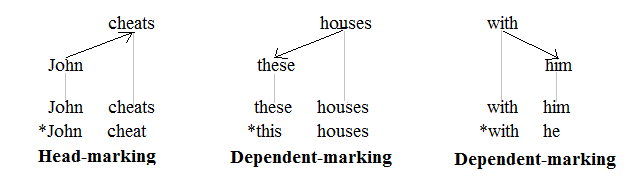

[edit]The concepts of head-marking and dependent-marking are commonly applied to languages that have richer inflectional morphology than English. There are, however, a few types of agreement in English that can be used to illustrate those notions. The following graphic representations of a clause, a noun phrase, and a prepositional phrase involve agreement. The three tree structures shown are those of a dependency grammar, as opposed to those of a phrase structure grammar:[2]

Heads and dependents are identified by the actual hierarchy of words, and the concepts of head-marking and dependent-marking are indicated with the arrows. Subject-verb agreement, shown in the tree on the left, is a case of head-marking because the singular subject John requires the inflectional suffix -s to appear on the finite verb cheats, the head of the clause. The determiner-noun agreement, shown in the tree in the middle, is a case of dependent-marking because the plural noun houses requires the dependent determiner to appear in its plural form, these, not in its singular form, this. The preposition-pronoun agreement of case government, shown in the tree on the right, is also an instance of dependent-marking because the head preposition with requires the dependent pronoun to appear in its object form, him, not in its subject form, he.

Noun phrases and verb phrases

[edit]The distinction between head-marking and dependent-marking shows the most in noun phrases and verb phrases, which have significant variation among and within languages.[3]

Phrase type Head Dependents Global distribution map (WALS) Noun phrase Nouns adjectives, possessives, relative clauses, etc. Marking in Possessive Noun Phrases Verb phrase (theory A) Verb verb arguments Marking in the Clause: Head-marking Verb phrase (theory B) Subject verbs Marking in the Clause: Dependent-marking

Languages may be head-marking in verb phrases and dependent-marking in noun phrases, such as most Bantu languages, or vice versa, and it has been argued that the subject rather than the verb is the head of a clause so "head-marking" is not necessarily a coherent typology. Still, languages that are head-marking in both noun and verb phrases are common enough to make the term useful for typological description.

Geographical distribution

[edit]Head-marked possessive noun phrases are common in the Americas, Melanesia, Afro-Asiatic languages (status constructus) and Turkic languages and infrequent elsewhere. Dependent-marked noun phrases have a complementary distribution and are frequent in Africa, Eurasia, Australia, and New Guinea, the only area in which both types overlap appreciably. Double-marked possession is rare but found in languages around the Eurasian periphery such as Finnish, in the Himalayas, and along the Pacific Coast of North America. Zero-marked possession is also uncommon, with instances mostly found near the equator, but it does not form any true clusters.[4]

The head-marked clause is common in the Americas, Australia, New Guinea, and the Bantu languages but is very rare elsewhere. The dependent-marked clause is common in Eurasia and Northern Africa, sparse in South America, and rare in North America. In New Guinea, it clusters in the Eastern Highlands and in Australia in the south, east, and interior with the very old Pama-Nyungan family. Double-marking is moderately well attested in the Americas, Australia, and New Guinea, and the southern fringe of Eurasia (chiefly in the Caucasian languages and Himalayan mountain enclaves), and it is particularly favored in Australia and the westernmost Americas. The zero-marked object is unsurprisingly common in Southeast Asia and Western Africa, two centers of morphological simplicity, but it is also very common in New Guinea and moderately common in Eastern Africa and Central America and South America, among languages of average or higher morphological complexity.[5][6]

The Pacific Rim distribution of head-marking may reflect population movements beginning tens of thousands of years ago and founder effects. Kusunda has traces in the Himalayas, and there are Caucasian enclaves, both of which are perhaps remnants of typology preceding the spreads of interior Eurasian language families. The dependent-marking type is found everywhere but rare in the Americas, possibly another result of founder effects. In the Americas, all four types are found along the Pacific Coast, but in the East, only head-marking is common. Whether the diversity of types along the Pacific Coast reflects a great age or an overlay of more recent Eurasian colonizations on an earlier American stratum remains to be seen.[7]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ See Nichols (1986).

- ^ Dependency grammar trees similar to the ones that are shown can be found in, for instance, Ágel et al. (2003/6).

- ^ The World Atlas of Language Structures is dedicated in part to documenting the distribution of head-marking and dependent-marking in noun and verb phrases among the world's languages.

- ^ WALS - Locus of Marking in Possessive Noun Phrases

- ^ WALS - Locus of Marking in the Clause

- ^ See Nichols (1992).

- ^ WALS - Locus of Marking: Whole-language Typology

References

[edit]- Ágel, V., L. Eichinger, H.-W. Eroms, P. Hellwig, H. Heringer, and H. Lobin (eds.) 2003/6. Dependency and Valency: An International Handbook of Contemporary Research. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Nichols, J. 1986. "Head-marking and dependent-marking grammar," in Language 62, 1, 56-119.

- Nichols, J. 1992. Linguistic Diversity in Space and Time. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.