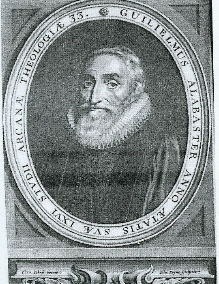

William Alabaster

This article has an unclear citation style. (July 2024) |

William Alabaster (also Alablaster, Arblastier) (27 February 1567 – buried 28 April 1640)[1] was an English Neo-Latin poet, playwright, and religious writer.[a][2]

Alabaster became a Roman Catholic convert in Spain when on a diplomatic mission as chaplain. His religious beliefs led him to be imprisoned several times; eventually he gave up Catholicism, and was favoured by James I. He received a prebend in St Paul's Cathedral, London, and the living of Therfield, Hertfordshire. He died at Little Shelford, Cambridgeshire.

Biography

[edit]

Alabaster was born at Hadleigh, Suffolk,[3] the son of Roger Alabaster of the Puritan cloth merchant family long settled there, and Bridget Winthrop of Groton, Suffolk.[b][4] Through his mother, Alabaster was the first cousin of John Winthrop, the future Governor of Massachusetts Bay Colony.[5]

According to Fr. John Gerard, an underground Roman Catholic priest of the Society of Jesus who briefly served as the former clergyman's spiritual director, Alabaster was, "raised in Calvin's bosom."[6]

He was educated at Westminster School, and Trinity College, Cambridge from 1583.[3][7] He became a fellow of Trinity, and in 1592 was incorporated of the university of Oxford.[3]

In June 1596 Alabaster sailed with Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, on the expedition to Cadiz in the capacity of Anglican military chaplain, and, while accompanying a subsequent diplomatic mission to Spain, Alabaster converted from Anglicanism to Roman Catholicism. An account of his conversion is given in an obscurely worded sonnet contained in a manuscript copy of Divine Meditations, by Mr Alabaster.[8]

Louise Imogen Guiney, however, gives a different account of Alabaster's conversion. After returning from the diplomatic mission, the Earl of Essex had arranged for Alabaster to be assigned as Vicar of Landulph, in Cornwall. Alabaster had sought the parish because he was engaged to be married and the living was worth 400 crowns a year, which he first received on 8 September 1596.[5]

According to Guiney, Sir Richard Topcliffe and other priest hunters covertly recruited Alabaster to meet with and persuade to convert to Anglicanism an underground Jesuit priest named Thomas Wright, the author, among many other volumes, of the samizdat book Passions of the Mind. Instead, "Wright by the force of his reasoning had persuaded Alabaster of the truth of the Catholic religion". According to Guiney, the date of Alabaster's covert reception into the illegal and underground Catholic Church in England, which caused the Vicar to willingly surrender both his living and his engagement, is fixed by an entry in his cousin Adam Winthrop's diary as 13 July 1597.[5]

Alabaster defended his new Faith in a pamphlet, Seven Motives, of which no copy is extant.[c]

After his conversion and in about 1597, Alabaster wrote his Latin tragedy of Roxana, which Samuel Johnson later called, "a tragedy against the Church of England.[9]

It appears that Alabaster was imprisoned for his change of faith in the Tower of London[3] and in The Clink in 1597 and 1598.[10] According to historian Robert Caraman, during his incarceration, Alabaster adapted the sonnet form from love poetry into Christian poetry. Alabaster's 85-long sonnet sequence, which "portray some profound spiritual experiences", were mainly, "written in 1597 while he was in The Clink prison and was conscious (as he himself says) of unwonted inspiration."[10] Another source of "unwonted inspiration" for Alabaster's religious poetry was, according to Gary Bouchard, the samizdat verse of recently martyred Jesuit priest Robert Southwell.[11]

After his escape from The Clink, which John Chamberlain reported to Sir Dudley Carleton on 4 May 1598,[12] Fr. John Gerard concealed William Alabaster for two or three months in a London safe house and secret Catholic chapel overseen by Anne Line and Fr. Robert Drury.[13]

According to Fr. John Gerard, "He was a learned man and spoke several languages. In order to become a Catholic he had declined many offers of high preferment in his church. Already he had had a taste of prison, and when he was offered the chance of escaping, I told him he could stay at my house."[14]

During those months time, Fr. Gerard led Alabaster through a guided retreat based on The Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius Loyola and Alabaster expressed a desire to enter the Jesuit Order.[13]

Fr. Gerard was reportedly very surprised and asked Alabaster, who, " "was used to having his own way over other people", to explain why he wished to join the Society, "when he knew, or should know, that it meant just the contrary of all he was used to."[6]

Alabaster's answer satisfied Fr. Gerard's concerns, and the latter arranged to smuggle the former Anglican clergyman, very likely through the Antwerp-based network led by Richard Verstegan, to the Spanish Netherlands and gave Alabaster 300 florins towards his future expenses.[6]

In a subsequent interrogation on 22 July 1600, Alabaster admitted to receiving another £30 in Brussels and to having travelled to meet Fr. Robert Persons in Rome.[15]

In 1607 Alabaster published at Antwerp Apparatus in Revelationem Jesu Christi, in which he used his study of the Kabbalah to give a mystical interpretation to the Christian Bible. The book was placed on the Vatican's Index Librorum Prohibitorum early in 1610. He went to Rome and was imprisoned for a time by the Roman Inquisition, but succeeded in returning to England and again conformed to the Established Church of the Realm.[16]

After returning to England, Alabaster became a doctor of divinity at Cambridge University and chaplain to King James I. After his marriage in 1618 his life now became more settled and he devoted his later years to theological studies.[3][17] He had an appreciable library, and books with his inscription can be found in numerous libraries today.[18]

Personal life

[edit]In 1618 Alabaster married Katherine Fludd, a widow, and was linked by marriage to the celebrated physician and alchemist Robert Fludd.[3]

Death

[edit]He died in 1640[3] after serving as Vicar of St. Dunstan's-in-the-West, at Little Shelford, Cambridgeshire.

Works

[edit]Roxana is modelled on the tragedies of Seneca, and is a stiff and spiritless work.[d] Fuller and Anthony à Wood bestowed exaggerated praise on it, while Samuel Johnson regarded it as the only Latin verse worthy of notice produced in England before Milton's elegies. Roxana is founded on the La Dalida (Venice, 1583) of Luigi Groto, known as Cieco di Hadria, and Hallam asserts that it is a plagiarism.[19]

A surreptitious edition in 1632 was followed by an authorized version a plagiarii unguibus vindicata, aucta et agnita ab Aithore, Gulielmo, Alabastro. One book of an epic poem in Latin hexameters, in honour of Queen Elizabeth, is preserved in manuscript (MS) in the library of Emmanuel College, Cambridge. This poem, Elisaeis, Apotheosis poetica, Spenser highly esteemed. "Who lives that can match that heroick song?" he says in Colin Clout's come home againe, and begs "Cynthia" to withdraw the poet from his obscurity.[3][3]

Alabaster's later cabalistic writings are Commentarius de Bestia Apocalyptica (1621) and Spiraculum tubarum (1633), a mystical interpretation of the Pentateuch. These theological writings won the praise of Robert Herrick, who calls him "the triumph of the day" and the "one only glory of a million".[3]

List of works:[3]

- Roxana – (c. 1595) Latin drama.

- Elisaeis – Latin epic on Elizabeth I.

- Apparatus in Revelationem Jesu Christi (1607).

- De bestia Apocalypsis (1621)

- Ecce sponsus venit (1633)

- Spiraculum Tubarum (1633)

- Schindleri lexicon pentaglotton in epitomen redactum a G. A.

- Lexicon Pentaglotton, Hebraicum, Chaldaicum, Syriacum, Talmudico-Rabbinicon et Arabicum (1637)

Notes

[edit]- ^ His surname, sometimes written Arblastier, is one of the many variants of arbalester, a cross-bowman.Chisholm 1911, p. 466

- ^ He was, so Fuller states, a nephew by marriage of Dr John Still, Bishop of Bath and Wells (Chisholm 1911, p. 466). Bridget Winthrop was the sister of Adam Winthrop (1548–1623) whose first wife was Alice Still, sister of Bishop John Still. The marriage was short; she died three years later in childbirth.[4]

- ^ The proof of its publication only remains in two tracts, A Booke of the Seuen Planets, or Seuen wandring motives of William Alablaster's wit, by John Racster (1598), and An Answer to William Alabaster, his Motives, by Roger Fenton (1599).[3]

- ^ For an analysis of the Roxana see an article on the Latin university plays in the Jahrbuch der Deutschen Shakespeare Gesellschaft (Weimar, 1898).[3]

- ^ Bremer, Francis J. "Alabaster, William". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/265. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "New General Catalog of Old Books & Authors".

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Chisholm 1911, p. 466.

- ^ a b Fuller, vol ii, p. 343; Camp, p. [page needed]

- ^ a b c Louise Imogen Guiney (1939), The Recusant Poets: With a Selection from their Work: From Thomas More to Ben Jonson, Sheed & Ward. Page 335.

- ^ a b c John Gerard, S.J. (2012), The Autobiography of a Hunted Priest, Ignatius Press. Page 176.

- ^ ACAD & ALBR584W.

- ^ see J. P. Collier, Hist. of Eng. Dram. Poetry, ii. 341.Chisholm 1911, p. 466

- ^ John Gerard, S.J. (2012), The Autobiography of a Hunted Priest, Ignatius Press. Page 308.

- ^ a b John Gerard, S.J. (2012), The Autobiography of a Hunted Priest, Ignatius Press. Pages 308-309.

- ^ Gary Bouchard (2018), Southwell's Sphere: The Influence of England's Secret Poet, St Augustine's Press, South Bend, Indiana. Pages 40-52.

- ^ Louise Imogen Guiney (1939), The Recusant Poets: With a Selection from their Work: From Thomas More to Ben Jonson, Sheed & Ward. Page 336.

- ^ a b John Gerard, S.J. (2012), The Autobiography of a Hunted Priest, Ignatius Press. Page 175-176.

- ^ John Gerard, S.J. (2012), The Autobiography of a Hunted Priest, Ignatius Press. Page 175.

- ^ John Gerard, S.J. (2012), The Autobiography of a Hunted Priest, Ignatius Press. Page 309.

- ^ Chisholm 1911, p. 466 citing the preface to Alabaster's Ecce sponsus venit (1633), a treatise on the time of the second advent of Christ

- ^ Drabble 2000, p. 13.

- ^ "William Alabaster | English scholar". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- ^ Chisholm 1911, p. 466 cites Hallam Literature of Europe, iii.54.

References

[edit]- "Alabaster, William (ALBR584W)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- Camp, Charles L. N. Winthrop family tree. New Haven, Conn.[full citation needed] – Traces the lineage of the Winthrop family from 1498 forward 200 years.

- Drabble, Margaret, ed. (2000). The Oxford Companion to English Literature (6th ed.). Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Fuller, Thomas. Worthies of England. Vol. ii. p. 343.

- William Alabaster, Book Owners Online.

Attribution

[edit]- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Alabaster, William". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 466. Endnotes:

- T. Fuller, Worthies of England (ii. 343)

- J. P. Collier, Bibl. and Crit. Account of the Rarest Books in the English Language (vol. i. 1865)

- Pierre Bayle, Dictionary, Historical and Critical (ed. London, 1734)

- The Athenaeum (December 26, 1903), where Mr. Bertram Dobell describes a MS. in his possession containing forty-three sonnets by Alabaster.

Further reading

[edit]- Story, G. M.; Gardener, Helen, eds. (1959). The Sonnets of William Alabaster.

- Sullivan, Ceri Sullivan. Dismembered Rhetoric: English Recusant Writing, 1580–1603.

- Sullivan, Ceri Sullivan (2000). "The physiology of penance in weeping texts of 1590s". Cahiers Élisabéthains. 57: 31 48. doi:10.7227/CE.57.1.3. S2CID 192141807. both books Ceri Sullivan, examine Alabaster's prose and poetry respectively.

External links

[edit]- 1567 births

- 1640 deaths

- People educated at Westminster School, London

- Converts to Roman Catholicism from Anglicanism

- Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge

- 17th-century English poets

- 17th-century English male writers

- 17th-century English writers

- English dramatists and playwrights

- People from Hadleigh, Suffolk

- English Roman Catholics

- 16th-century English poets

- 17th-century English Anglican priests

- 16th-century Roman Catholics

- 17th-century Roman Catholics

- English religious writers

- English male dramatists and playwrights

- English male poets

- Escapees from England and Wales detention

- People from Little Shelford

- 16th-century writers in Latin

- 17th-century writers in Latin

- Neo-Latin poets

- Winthrop family

- Sonneteers