Gerstmann–Sträussler–Scheinker syndrome

| Gerstmann–Sträussler–Scheinker syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

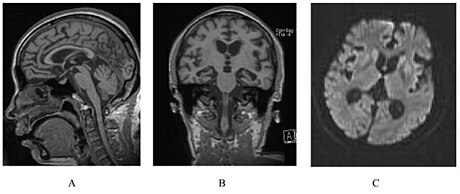

| A person with inherited prion disease has cerebellar atrophy. This is quite typical of GSS. | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

| Symptoms | difficulty speaking, developing dementia, memory loss, vision loss. |

| Causes | Prions |

| Prognosis | Universally fatal, life expectancy is typically 5-6 years from diagnosis |

Gerstmann–Sträussler–Scheinker syndrome (GSS) is an extremely rare, always fatal (due to it being caused by prions) neurodegenerative disease that affects patients from 20 to 60 years in age. It is exclusively heritable, and is found in only a few families all over the world.[1] It is, however, classified with the transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSE) due to the causative role played by PRNP, the human prion protein.[2] GSS was first reported by the Austrian physicians Josef Gerstmann, Ernst Sträussler and Ilya Scheinker in 1936.[3][4]

Familial cases are associated with autosomal-dominant inheritance.[5]

Certain symptoms are common to GSS, such as progressive ataxia, pyramidal signs, and dementia; they worsen as the disease progresses.[6]

Symptoms and signs

[edit]Symptoms start with slowly developing dysarthria (difficulty speaking) and cerebellar truncal ataxia (unsteadiness) and then the progressive dementia becomes more evident. In the early stages of GSS, people with the condition may also exhibit clumsiness and experience difficulty walking. As the condition progresses, symptoms of ataxia become more pronounced.[7] Loss of memory can be the first symptom of GSS.[8] Extrapyramidal and pyramidal symptoms and signs may occur and the disease may mimic spinocerebellar ataxias in the beginning stages. Myoclonus (spasmodic muscle contraction) is less frequently seen than in Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. Many patients also exhibit nystagmus (involuntary movement of the eyes), visual disturbances, and even blindness or deafness.[9] The neuropathological findings of GSS include widespread deposition of amyloid plaques composed of abnormally folded prion protein.[8]

Four clinical phenotypes are recognized: typical GSS, GSS with areflexia and paresthesia, pure dementia GSS and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease-like GSS.[10]

Causes

[edit]GSS is part of a group of diseases called transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. These diseases are caused by prions, which are a class of pathogenic proteins that are resistant to proteases. These prions then form clusters in the brain, which are responsible for the neurodegenerative effects seen in patients.[11]

The P102L mutation, which causes a substitution of proline to a leucine in codon 102, has been found in the prion protein gene (PRNP, on chromosome 20) of most affected individuals.[12] Therefore, it appears this genetic change is usually required for the development of the disease.[13][14][15]

Diagnosis

[edit]GSS can be identified through genetic testing.[9] Testing for GSS involves a blood and DNA examination in order to attempt to detect the mutated gene at certain codons. If the genetic mutation is present, the patient will eventually develop GSS.

Treatment

[edit]There is no cure for GSS, nor is there any known treatment to slow the progression of the disease. Therapies and medication are aimed at treating or slowing down the effects of the symptoms. The goal of these treatments is to try to improve the patient's quality of life as much as possible. There is some ongoing research to find a cure, with one of the most prominent examples being the PRN100 monoclonal antibody.[citation needed]

Prognosis

[edit]GSS is a disease that progresses slowly, lasting roughly 2–10 years, with an average of approximately five years.[8][1]

Symptoms as clumsiness and unsteadiness when walking at the beginning of the illness. Muscle jerking (myoclonus) is much less common than in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Speaking becomes difficult (called dysarthria), and dementia develops. Nystagmus (rapid movement of the eyes in one direction, followed by a slower drift back to the original position) and deafness may develop. Muscle coordination is lost (called ataxia). The muscles may become stiff. Usually, the muscles that control breathing and coughing are impaired, resulting in a high risk of pneumonia, which is the most common cause of death.

The disease ultimately results in death, most commonly from the patient either going into a coma, or from a secondary infection due to the patient's loss of bodily functions.[1]

Research

[edit]Prion diseases, also called transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), are neurodegenerative diseases of the brain thought to be caused by a protein that converts to an abnormal form called a prion.[16][17] GSS is a very rare TSE, making its genetic origin nearly impossible to determine. It is also challenging to find any patients with GSS, as the disease tends to be underreported, due to its clinical similarity to other diseases, and has been found in only a few countries.[18] In 1989, the first mutation of the prion protein gene was identified in a GSS family.[15] The largest of these families affected by GSS is the Indiana Kindred, spanning over 8 generations, and includes over 3,000 people, with 57 individuals known to be affected.[14] GSS was later realized to have many different gene mutation types, varying in symptom severity, timing and progression. Doctors in different parts of the world are in the process of uncovering more generations and families who have the mutation.[citation needed]

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c "Gerstmann-Straussler-Scheinker Disease Information Page". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Retrieved 2021-04-18.

- ^ Liberski PP (2012). "Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker Disease". Neurodegenerative Diseases. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 724. pp. 128–37. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-0653-2_10. ISBN 978-1-4614-0652-5. PMID 22411239.

- ^ synd/2269 at Who Named It?

- ^ Gerstmann J, Sträussler E, Scheinker I (1936). "Über eine eigenartige hereditär-familiäre Erkrankung des Zentralnervensystems. Zugleich ein Beitrag zur Frage des vorzeitigen lokalen Alterns". Zeitschrift für die gesamte Neurologie und Psychiatrie. 154: 736–762. doi:10.1007/bf02865827. S2CID 86904496.

- ^ De Michele G, Pocchiari M, Petraroli R, Manfredi M, Caneve G, Coppola G, et al. (August 2003). "Variable phenotype in a P102L Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker Italian family". The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences. 30 (3): 233–6. doi:10.1017/S0317167100002651. PMID 12945948.

- ^ Farlow MR, Yee RD, Dlouhy SR, Conneally PM, Azzarelli B, Ghetti B (November 1989). "Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker disease. I. Extending the clinical spectrum". Neurology. 39 (11): 1446–52. doi:10.1212/wnl.39.11.1446. PMID 2812321. S2CID 23716392.

- ^ "Gerstmann-Straussler-Scheinker Disease". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ a b c Collins S, McLean CA, Masters CL (September 2001). "Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker syndrome,fatal familial insomnia, and kuru: a review of these less common human transmissible spongiform encephalopathies". Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 8 (5): 387–97. doi:10.1054/jocn.2001.0919. PMID 11535002. S2CID 31976428.

- ^ a b Gambetti P. "Gerstmann–Sträussler–Scheinker Disease". The Merck Manuals: Online Medical Library. Archived from the original on February 22, 2011. Retrieved April 6, 2011.

- ^ Tesar A, Matej R, Kukal J, Johanidesova S, Rektorova I, Vyhnalek M, Keller J, Eliasova I, Parobkova E, Smetakova M, Musova Z, Rusina R (November 2019). "Clinical Variability in P102L Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker Syndrome". Annals of Neurology. 86 (5): 643–652. doi:10.1002/ana.25579. PMID 31397917. S2CID 199504473.

- ^ Poggiolini I, Saverioni D, Parchi P (2013). "Prion protein misfolding, strains, and neurotoxicity: an update from studies on Mammalian prions". International Journal of Cell Biology. 2013: 910314. doi:10.1155/2013/910314. PMC 3884631. PMID 24454379.

- ^ Arata H, Takashima H, Hirano R, Tomimitsu H, Machigashira K, Izumi K, et al. (June 2006). "Early clinical signs and imaging findings in Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker syndrome (Pro102Leu)". Neurology. 66 (11): 1672–8. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000218211.85675.18. PMID 16769939. S2CID 26013402.

- ^ Umeh CC, Kalakoti P, Greenberg MK, Notari S, Cohen Y, Gambetti P, et al. (2016-02-18). "Clinicopathological Correlates in a PRNP P102L Mutation Carrier with Rapidly Progressing Parkinsonism-dystonia". Movement Disorders Clinical Practice. 3 (4): 355–358. doi:10.1002/mdc3.12307. PMC 5015693. PMID 27617269.

- ^ a b Ghetti B, Piccardo P, Frangione B, Bugiani O, Giaccone G, Young K, et al. (April 1996). "Prion protein amyloidosis". Brain Pathology. 6 (2): 127–45. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3639.1996.tb00796.x. PMID 8737929. S2CID 10240829.

- ^ a b Hsiao K, Baker HF, Crow TJ, Poulter M, Owen F, Terwilliger JD, et al. (March 1989). "Linkage of a prion protein missense variant to Gerstmann-Sträussler syndrome". Nature. 338 (6213): 342–5. Bibcode:1989Natur.338..342H. doi:10.1038/338342a0. PMID 2564168. S2CID 4319741.

- ^ Zou WQ, Gambetti P, Xiao X, Yuan J, Langeveld J, Pirisinu L (July 2013). "Prions in variably protease-sensitive prionopathy: an update". Pathogens. 2 (3): 457–71. doi:10.3390/pathogens2030457. PMC 4235694. PMID 25437202.

- ^ Gambetti P (March 2013). "Creationism and evolutionism in prions". The American Journal of Pathology. 182 (3): 623–7. doi:10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.12.016. PMC 3590995. PMID 23380581.

- ^ Ghetti B, Tagliavini F, Takao M, Bugiani O, Piccardo P (March 2003). "Hereditary prion protein amyloidoses". Clinics in Laboratory Medicine. 23 (1): 65–85, viii. doi:10.1016/s0272-2712(02)00064-1. PMID 12733425.

External links

[edit]- Gerstmann–Sträussler–Scheinker syndrome Archived 2013-05-11 at the Wayback Machine, MedicineNet.com

- ITALIAN ASSOCIATION AGAINST GERSTMANN STRAUSSLER SCHEINKER'S DISEASE