Muscovy duck

| Muscovy duck | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Anseriformes |

| Family: | Anatidae |

| Genus: | Cairina Fleming, 1822 |

| Species: | C. moschata

|

| Binomial name | |

| Cairina moschata (Linnaeus, 1758)

| |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| |

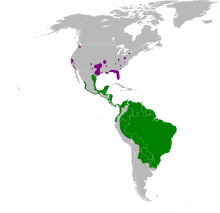

Natural range Introduced feral populations

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Anas moschata Linnaeus, 1758 | |

The Muscovy duck (Cairina moschata) is a duck native to the Americas, from the Rio Grande Valley of Texas and Mexico south to Argentina and Uruguay. Feral Muscovy ducks are found in New Zealand, Australia, and in Central and Eastern Europe. Small wild and feral breeding populations have also established themselves in the United States, particularly in Florida, Louisiana, Massachusetts, the Big Island of Hawaii, as well as in many other parts of North America, including southern Canada.[3][4]

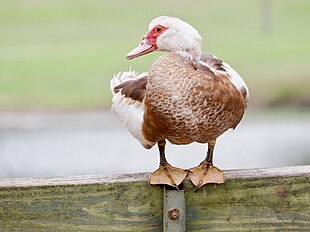

It is a large duck, with the males about 76 cm (30 in) long, and weighing up to 7 kg (15 lb). Females are noticeably smaller, and only grow to 3 kg (6.6 lb), roughly half the males' size. The bird is predominantly black and white, with the back feathers being iridescent and glossy in males, while the females are more drab. The amount of white on the neck and head is variable, as well as the bill, which can be yellow, pink, black, or any mixture of these colors. It may have white patches or bars on the wings, which become more noticeable during flight. Both sexes have pink or red wattles around the bill, those of the male being larger and more brightly colored.[5][6]

Although the Muscovy duck is a tropical bird, it adapts well to cooler climates, thriving in weather as cold as −12 °C (10 °F) and able to survive even colder conditions.[7][8] In general, Barbary duck is the term used for C. moschata in a culinary context.

The domestic subspecies, Cairina moschata domestica, is commonly known in Spanish as the pato criollo. They have been bred since pre-Columbian times by Native Americans and are heavier and less able to fly long distances than the wild subspecies. Their plumage color is also more variable. Other names for the domestic breed in Spanish are pato casero ("household duck") and pato mudo ("mute duck").

Description

[edit]

All Muscovy ducks have long claws on their feet and a wide, flat tail. In the domestic drake (male), length is about 86 cm (34 in) and weight is 4.6–6.8 kg (10–15 lb), while the domestic hen (female) is much smaller, at 64 cm (25 in) in length and 2.7–3.6 kg (6.0–7.9 lb) in weight. Large domesticated males often weigh up to 7 kg (15 lb), and large domesticated females up to 4 kg (8.8 lb).

The true wild Muscovy duck, from which all domestic Muscovies originated, is blackish, with large white wing patches. Length can range from 66 to 84 cm (26 to 33 in), wingspan from 137 to 152 cm (54 to 60 in) and weight from 1.1 to 4.1 kg (2.4 to 9.0 lb). On the head, the wild male has a short crest on the nape. The bill is black with a speckling of pale pink. A blackish or dark red knob can be seen at the bill base, which is similar in colour to the bare skin of the face. The eyes are yellowish-brown. The legs and webbed feet are blackish. The wild female is similar in plumage, but much smaller, with a feathered face and lacking the prominent knob. The juvenile is duller overall, with little or no white on the upperwing.[9]

Domesticated birds may look similar; most are dark brown or black mixed with white, particularly on the head.[10] Other colors, such as lavender or all-white, are also seen. Both sexes have a nude black-and-red or all-red face; the drake also has pronounced caruncles at the base of the bill and a low erectile crest of feathers.[8] C. moschata ducklings are mostly yellow with buff-brown markings on the tail and wings. For a while after hatching, juveniles lack the distinctive wattles associated with adult individuals, and resemble the offspring of various other ducks, such as mallards. Some domesticated ducklings have a dark head and blue eyes, others a light brown crown and dark markings on their nape. They are agile and speedy precocial birds.

The drake has a low breathy call, and the hen a quiet trilling coo.

The karyotype of the Muscovy duck is 2n=80, consisting of three pairs of macrochromosomes, 36 pairs of microchromosomes, and a pair of sex chromosomes. The two largest macrochromosome pairs are submetacentric, while all other chromosomes are acrocentric or probably telocentric for the smallest microchromosomes. The submetacentric chromosomes and the Z (female) chromosome show rather little constitutive heterochromatin (C bands), while the W chromosomes are at least two-thirds heterochromatin.[11]

Male Muscovy ducks have helical penises that become erect to 19 cm (7 in) in 0.3 s. Females have vaginas that coil in the opposite direction that appear to have evolved to limit forced copulation by males.[12][13]

Etymology

[edit]Common name “Muscovy”

[edit]

"Muscovy" is an old name for the region of Russia surrounding Moscow, but these ducks are neither native there nor were introduced there before they became known in Western Europe. It is not quite clear how the term came about; it very likely originated between 1550 and 1600, but did not become widespread until somewhat later.

In one suggestion, it has been claimed that the Company of Merchant Adventurers to New Lands traded these ducks to Europe occasionally after 1550;[14] this chartered company became eventually known as the "Muscovy Company" or "Muscovite Company" so the ducks might thus have come to be called "Muscovite ducks" or "Muscovy ducks" in keeping with the common practice of attaching the importer's name to the products they sold.[14] But while the Muscovite Company initiated vigorous trade with Russia, they hardly, if at all, traded produce from the Americas; thus, they are unlikely to have traded C. moschata to a significant extent.

Alternatively—just as in the "turkey" (which is also from North America, not Turkey) and the "guineafowl" (which are not limited to Guinea)—"Muscovy" might be simply a generic term for an exotic place, in reference to the singular appearance of these birds. This is evidenced by other names suggesting the species came from lands where it is not actually native, but from where much "outlandish" produce was imported at that time (see below).

Yet another view—not incompatible with either of those discussed above—connects the species with the Muisca, a Native American nation in today's Colombia. The duck is native to these lands also, and it is likely that it was kept by the Muisca as a domestic animal to some extent. It is conceivable that a term like "Muisca duck", hard to comprehend for the average European of those times, would be corrupted into something more familiar. Likewise, the Miskito Indians of the Miskito Coast in Nicaragua and Honduras heavily relied on it as a domestic species, and the ducks as well may have been named after this region.

Species name “moschata”

[edit]

Linnaeus’ description of Anas moschata only consists of a curt but entirely unequivocal [Anas] facie nuda papillosa ("A duck with a naked and carunculated face"), and his primary reference is his earlier work Fauna Svecica.[15] But Linnaeus refers also to older sources, wherein much information on the origin of the common name is found.

Conrad Gessner is given by Linnaeus as a source, but the Historia animalium mentions the Muscovy duck only in passing.[16] Ulisse Aldrovandi[17] discusses the species in detail, referring to the wild birds and its domestic breeds variously as anas cairina, anas indica or anas libyca – "duck from Cairo", "Indian duck" (in reference to the West Indies) or "Libyan duck". But his anas indica (based, like Gessner's brief discussion, ultimately on the reports of Christopher Columbus's travels) also seems to have included another species,[18] perhaps a whistling-duck (Dendrocygna). Already however the species is tied to some more or less nondescript "exotic" locality – "Libya" could still refer to any place in Northern Africa at that time – where it did not natively occur. Francis Willughby discusses "The Muscovy duck" as anas moschata and expresses his belief that Aldrovandi's and Gessner's anas cairina, anas indica and anas libyca (which he calls "The Guiny duck", adding another mistaken place of origin to the list) refer to the very same species.[19] Finally, John Ray attempts to clear up the confusion by providing an alternative explanation for the name's etymology:

In English, it is called The Muscovy-Duck, though this is not transferred from Muscovia [the Neo-Latin name of Muscovy], but from the rather strong musk odour it exudes.[20]

Linnaeus came to witness the birds' "gamey" aroma first-hand, as he attests in the Fauna Svecica and again in the travelogue of this 1746 Västergötland excursion.[15][21] Similarly, the Russian name of this species, muskusnaya utka (Мускусная утка), means "musk duck" – without any reference to Moscow – as do the Bokmål and Danish moskusand, Dutch muskuseend, Finnish myskisorsa, French canard musqué, German Moschusente, Italian anatra muschiata, Spanish pato almizclado and Swedish myskand. In English, however, musk duck refers to the Australian species Biziura lobata.

Genus name "Cairina"

[edit]The currently assigned genus name Cairina, meanwhile, traces its origin to Aldrovandi and the mistaken belief that the birds came from Egypt: translated, the current scientific name of the Muscovy duck means "the musky one from Cairo".

Other names

[edit]In some regions the name "Barbary duck" is used for domestic and "Muscovy duck" for wild birds; in other places, "Barbary duck" refers specifically to the dressed carcass, while "Muscovy duck" applies to living C. moschata, regardless of whether they are wild or domestic. In general, "Barbary duck" is the usual term for C. moschata in a culinary context.

Taxonomy and systematics

[edit]

The species was first scientifically described by Carl Linnaeus in his 1758 edition of Systema Naturae as Anas moschata,[22] literally meaning "musk duck". It was later transferred to the genus Cairina, making its current binomial name Cairina moschata.

The Muscovy duck was formerly placed into the paraphyletic "perching duck" assemblage, but subsequently moved to the dabbling duck subfamily (Anatinae). Analysis of the mtDNA sequences of the cytochrome b and NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2 genes,[23] however, indicates that it might be closer to the genus Aix and better placed in the shelduck subfamily Tadorninae. In addition, the other species of Cairina, the rare white-winged duck (C. scutulata), seems to belong to a distinct genus (Asarcornis).

Ecology

[edit]This non-migratory species normally inhabits forested swamps, lakes, streams and nearby grassland and farm crops,[24] and often roosts in trees at night. The Muscovy duck's diet consists of plant material (such as the roots, stems, leaves, and seeds of aquatic plants and grasses, as well as terrestrial plants, including agricultural crops) obtained by grazing or dabbling in shallow water, and small fish, amphibians, reptiles, crustaceans, spiders, insects, millipedes, and worms.[25][26][27][28] This is an aggressive duck; males often fight over food, territory or mates. The females fight with each other less often. Some adults will peck at the ducklings if they are eating at the same food source.

The Muscovy duck has benefited from nest boxes in Mexico, but is somewhat uncommon in much of the eastern part of its range due to excessive hunting. It is not considered a globally threatened species by the IUCN, however, as it is widely distributed.[1]

Reproduction

[edit]

This species, like the mallard, does not form stable pairs. They will mate on land or in water. Domestic Muscovy ducks can breed up to three times each year.

The hen lays a clutch of 8–16 white eggs, usually in a tree hole or hollow, which are incubated for 35 days. The sitting hen will leave the nest once a day from 20 minutes to one and a half hours, and will then defecate, drink water, eat and sometimes bathe. Once the eggs begin to hatch, it may take 24 hours for all the chicks to break through their shells. When feral chicks are born, they usually stay with their mother for about 10–12 weeks. Their bodies cannot produce all the heat they need, especially in temperate regions, so they will stay close to the mother, especially at night.

Often, the drake will stay in close contact with the brood for several weeks. The male will walk with the young during their normal travels in search for food, providing protection. Anecdotal evidence from East Anglia, U.K. suggests that, in response to different environmental conditions, other adults assist in protecting chicks and providing warmth at night. It has been suggested that this is in response to local efforts to cull the eggs, which has led to an atypical distribution of males and females, as well as young and mature birds.

For the first few weeks of their lives, Muscovy chicks feed on grains, corn, grass, insects, and almost anything that moves. Their mother instructs them at an early age how to feed.

Feral bird

[edit]

Feral Muscovy ducks can breed near urban and suburban lakes and on farms, nesting in tree cavities or on the ground, under shrubs in yards, on apartment balconies, or under roof overhangs. Some feral populations, such as that in southern Florida, have a reputation of becoming pests on occasion.[29] At night they often sleep at water, if there is a water source available, to flee quickly from predators if awakened. Small populations of Muscovy ducks can also be found in Ely, Cambridgeshire, Calstock, Cornwall, and Lincoln, Lincolnshire, U.K. Muscovy ducks have also been spotted in the Walsall Arboretum. There has been a small population in the Pavilion Gardens public park in Buxton, Derbyshire for many years.[30]

In the U.S., Muscovy ducks are considered a non-native species. An owner may raise them for food production only (not for hunting). Similarly, if the ducks have no owner, 50CFR Part 21 (Migratory Bird Permits) allows the removal or destruction of the ducks, their eggs and their nests anywhere in the United States outside of Hidalgo, Starr and Zapata Counties in Texas, where they are considered indigenous. The population in southern Florida is considered, with numbers in the several thousands, to be established enough to be considered "countable" for bird watchers.[31]

Legal methods to restrict breeding include not feeding these ducks, deterring them with noise or chasing them away.

Although legislation passed in the U.S. prohibiting trade of Muscovy ducks, Fish and Wildlife Services intend to revise the regulations. They are not currently implementing them, though release of Muscovy ducks to the wild outside their natural range is prohibited.[32]

Domestication

[edit]

Muscovy ducks had been domesticated by various Native American cultures in the Americas when Columbus arrived in the Bahamas. A few were brought onto Columbus' ship the Santa Maria, they then sailed back to Europe by the 16th century.

The Muscovy duck has been domesticated for centuries, and is widely traded as "Barbary duck". Muscovy breeds are popular because they have stronger-tasting meat—sometimes compared to roast beef—than the usual domestic ducks, which are descendants of the mallard (Anas platyrhynchos). The meat is lean when compared to the fatty meat of mallard-derived ducks, its leanness and tenderness being often compared to veal. Muscovy ducks are also less noisy, and sometimes marketed as a "quackless" duck; even though they are not completely silent, they do not actually quack (except in cases of extreme stress). Many backyard duck owners report that Muscovy ducks have more personality than mallard-derived ducks, often comparing them to dogs for their tameness and willingness to approach owners for food or stroking.[33] The carcass of a Muscovy duck is also much heavier than most other domestic ducks, which makes it ideal for the dinner table.

Domesticated Muscovy ducks, like those pictured, often have plumage features differing from other wild birds. White breeds are preferred for meat production, as darker ones can have much melanin in the skin, which some people find unappealing.

The Muscovy duck can be crossed with mallards in captivity to produce hybrids known as mulards ("mule ducks") because they are sterile. Muscovy drakes are commercially crossed with mallard-derived hens either naturally or by artificial insemination. The 40–60% of eggs that are fertile result in birds raised only for their meat or for production of foie gras: they grow fast like mallard-derived breeds, but to a large size like Muscovy ducks. Conversely, though crossing mallard-derived drakes with Muscovy hens is possible, the offspring are neither desirable for meat nor for egg production.[34][35]

In addition, Muscovy ducks are reportedly crossbred in Israel with mallards to produce kosher duck products. The kashrut status of the Muscovy duck has been a matter of rabbinic discussion for over 150 years.[35]

A study examining birds in northwestern Colombia for blood parasites found the Muscovy duck to be more frequently infected with Haemoproteus and malaria (Plasmodium) parasites than chickens, domestic pigeons, domestic turkeys and, in fact, almost all wild bird species also studied. It was noted that in other parts of the world, chickens were more susceptible to such infections than in the study area, but it may well be that Muscovy ducks are generally more often infected with such parasites (which might not cause pronounced disease, though, and are harmless to humans).[36]

Gallery

[edit]-

Hatchling

-

Young duckling

-

Older duckling

-

Fledgling

-

One-year-old (still immature)

-

Mating pair

-

White Muscovy duck

-

Mating in water; the large drake entirely submerges the smaller hen

-

Black wild type Muscovy duck in Baton Rouge

-

Domestic ducklings after 25 days, left perhaps little distinction, the weight makes it clear that the male (1 and 2) are already heavier than the females (3 and 4).[37]

-

Domestic Muscovy duck

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b BirdLife International (2018). "Cairina moschata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T22680061A131911211. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22680061A131911211.en. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ Donkin 1988.

- ^ "Muscovy - an overview". Sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2021-06-17.

- ^ "Poultry Breeds - Muscovy Duck — Breeds of Livestock, Department of Animal Science". afs.okstate.edu. Retrieved 2021-06-17.

- ^ "Muscovy Duck". ebird.org. Retrieved 2021-06-17.

- ^ "Muscovy Duck". txtbba.tamu.edu. Retrieved 2021-06-17.

- ^ Holderread 2001, p. 17

- ^ a b "Non-Native Aquatic Species in the Gulf of Mexico and South Atlantic Regions". Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission. Archived from the original on 12 April 2008. Retrieved 6 February 2012.

- ^ "Muscovy Duck". Oiseaux-birds.com.

- ^ Cisneros-Heredia 2006.

- ^ Wójcik & Smalec 2008.

- ^ Brennan, P. L. R.; Clark, C. J.; Prum, R. O. (2009-12-23). "Explosive eversion and functional morphology of the duck penis supports sexual conflict in waterfowl genitalia". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 277 (1686): 1309–1314. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.2139. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 2871948. PMID 20031991.

- ^ Sample, Ian (23 December 2009). "Video reveals twists and turns of genital warfare in ducks". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- ^ a b Holderread 2001, pp. 73–74

- ^ a b Linnaeus, Carl (1746). "98". Fauna Svecica Sistens Animalia Sveciæ Regni, etc (in Latin) (1st: 35 ed.). Leiden ("Lugdunum Batavorum"): Conrad & Georg Jacob Wishoff.

- ^ Gessner 1555, p. 118; not p. 122 as per Linnaeus (1741, 1758): see Aldrovandi 1637, p. 192 and Willughby 1676, p. 295

- ^ Aldrovandi 1637, pp. 192–201

- ^ Aldrovandi 1637, pp. 192, 194: Anas indica alia

- ^ Willughby 1676, pp. 294–295

- ^ Ray, John (Joannis Raii) (1713): Synopsis methodica avium & piscium: opus posthumum Archived 2011-07-16 at the Wayback Machine, etc. (vol. 1) [in Latin]. William Innys, London, p. 150: Anglicē, the Muscovy-Duck dicitur, non quōd ē Muscovia huc translata esset, sed quōd satis validum moschi odorem spiret.

- ^ Linnaeus, Carl (1747). Anas facie nuda papillosa. Wästgöta-Resa, etc. 134 (in Swedish). Stockholm ("Holmius"): Lars Salvius. Archived from the original on 2013-02-12.

- ^ Linnaeus, Carl (1758). "61.13". Anas moschata. Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1 (10th ed.). Stockholm ("Holmius"): Lars Salvius. p. 124. Archived from the original on 2017-06-13. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- ^ Johnson & Sorenson 1999.

- ^ Accordi & Barcellos 2006.

- ^ "Cairina moschata (Wild Muscovy Duck)" (PDF). Sta.uwi.edu. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ "Cairina moschata (Muscovy duck)". Animal Diversity Web.

- ^ US Fish and Wildlife Service (1 March 2010). "Migratory Bird Permits; Control of Muscovy Ducks, Revisions to the Waterfowl Permit Exceptions and Waterfowl Sale and Disposal Permits Regulations" (PDF). Federal Register. 75 (39): 9316.

- ^ Eitniear, Jack C.; Bribiesca-Formisano, R.; Rodríguez-Flores, Claudia I.; Soberanes-González, Carlos A.; Arizmendi, Marîa del Coro (2020). "Muscovy Duck (Cairina moschata), version 1.0". Birds of the World. doi:10.2173/bow.musduc.01.

- ^ Johnson & Hawk 2009.

- ^ "Muscovy duck". Ispotnature.org. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ^ Pranty, Bill (24 May 2001). "Re: Red-crowned Parrot". Lists.ufl.edu. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service - Forms" (PDF). Fws.org.

- ^ Ruthersdale, Roland (2014). Muscovy Ducks as Pets: Muscovy Duck Owners Manual. IMB Publishing. p. 43. ISBN 978-1910410097.

- ^ Holderread 2001, p. 97

- ^ a b Zivotofsky, Rabbi Ari Z.; Amar, Zohar (2003). "The Halachic Tale of Three American Birds: Turkey, Prairie Chicken, and Muscovy Duck". Journal of Halacha and Contemporary Society. 6: 81–104.

- ^ Londoño, Pulgarin-R & Blair 2007.

- ^ "How to Tell the Difference in Male & Female Muscovy Ducks". Animals.mom.me.

Bibliography

[edit]- Accordi, Iury Almeida; Barcellos, André (2006). "Composição da avifauna em oito áreas úmidas da Bacia Hidrográfica do Lago Guaíba, Rio Grande do Sul" [Composition of the avifauna in eight wetlands of the Basin Lake Guaiba, Rio Grande do Sul]. Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia - Brazilian Journal of Ornithology (in Portuguese). 14 (2): 101–115. Archived from the original on 2014-11-08. Retrieved 2014-11-08.

- Aldrovandi, Ulisse (Ulyssis Aldrovandus) (1637). Ornithologia (in Latin). Vol. 3 (Tomus tertius ac postremus) (2nd ed.). Bologna ("Bononia"): Nicolò Tebaldini. Archived from the original on 2012-12-11. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- Cisneros-Heredia, Diego F. (2006). "Información sobre la distribución de algunas especies de aves de Ecuador" [Information on the distribution of some species of birds of Ecuador] (PDF). Boletín de la Sociedad Antioqueña de Ornitología (SAO) (in Spanish). 16 (1): 7–16. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 September 2007.

- Donkin, R. A. (1988). The Muscovy Duck: Cairina Moschata Domestica: Origins, Dispersal and Associated Aspects of Geography of Domestication. Routledge. ISBN 978-9061915447.

- Gessner, Conrad (1555). Historiae animalium (in Latin). Vol. 3. Zürich ("Tigurium"): Christoph Froschauer. Archived from the original on 2012-12-05. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- Holderread, David (2001). Storey's Guide to Raising Ducks. North Adams, MA: Storey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-58017-258-5.

- Johnson, Steve A.; Hawk, Michelle (2009). Florida's Introduced Birds: Muscovy Duck (Cairina moschata) (Thesis). University of Florida. Archived from the original on 2012-02-07. Retrieved 2009-06-16.

- Johnson, Kevin P.; Sorenson, Michael D. (1999). "Phylogeny and Biogeography of Dabbling Ducks (Genus: Anas): A Comparison of Molecular and Morphological Evidence". Auk. 116 (3): 792–805. doi:10.2307/4089339. JSTOR 4089339.

- Londoño, Aurora; Pulgarin-R, Paulo C.; Blair, Silvia (2007). "Blood Parasites in Birds From the Lowlands of Northern Colombia". Caribbean Journal of Science. 43 (1): 87–93. doi:10.18475/cjos.v43i1.a8. S2CID 87907947.

- Willughby, Francis (1676). Ornithologiae libri tres (in Latin). London: John Martyn. Archived from the original on 2012-12-09.

- Wójcik, Ewa; Smalec, Elżbieta (2008). "Description of the Muscovy Duck (Cairina moschata) Karyotype". Folia Biologica. 56 (3–4): 243–248. doi:10.3409/fb.56_3-4.243-248. PMID 19055053. S2CID 24245675.

Further reading

[edit]- "Nuisance Muscovy Ducks". Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FFWCC). 1999. Retrieved 18 November 2008.

- Maddox, John (1988). "When to believe the unbelievable". Nature. 333 (6176): 787. Bibcode:1988Natur.333Q.787.. doi:10.1038/333787a0. S2CID 4369459.

- Hilty, Steven L. (2003). Birds of Venezuela. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-7136-6418-8.

- Stiles, F. Gary; Skutch, Alexander F. (1989). A Guide to the Birds of Costa Rica. Comstock Publishing Associates. ISBN 978-0-8014-9600-4.

![Domestic ducklings after 25 days, left perhaps little distinction, the weight makes it clear that the male (1 and 2) are already heavier than the females (3 and 4).[37]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/cd/Moscovy_ducklings_weight_after_25_days.jpg/890px-Moscovy_ducklings_weight_after_25_days.jpg)