The Second Sex

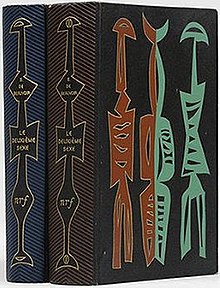

First editions | |

| Author | Simone de Beauvoir |

|---|---|

| Original title | Le Deuxième Sexe |

| Language | French |

| Subject | Feminism |

| Published | 1949 |

| Publication place | France |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 978 in 2 volumes[1][2] |

| Part of a series on |

| Feminist philosophy |

|---|

|

The Second Sex (French: Le Deuxième Sexe) is a 1949 book by the French existentialist philosopher Simone de Beauvoir, in which the author discusses the treatment of women in the present society as well as throughout all of history. Beauvoir researched and wrote the book in about 14 months between 1946 and 1949.[3] She published the work in two volumes: Facts and Myths, and Lived Experience. Some chapters first appeared in the journal Les Temps modernes.[4][5]

One of Beauvoir's best-known and controversial books (banned by the Vatican), The Second Sex is regarded as a groundbreaking work of feminist philosophy,[6] and as the starting inspiration point of second-wave feminism.[7]

Summary

[edit]Volume One

[edit]Beauvoir asks, "What is woman?"[8] She argues that man is considered the default, while woman is considered the "Other": "Thus, humanity is male, and man defines woman not herself, but as relative to him." Beauvoir describes the relationship of ovum to sperm in various creatures (fish, insects, mammals), leading up to the human being. She describes women's subordination to the species in terms of reproduction, compares the physiology of men and women, concluding that values cannot be based on physiology and that the facts of biology must be viewed in light of the ontological, economic, social, and physiological context.[9]

Authors whose views Beauvoir rejects include Sigmund Freud and Alfred Adler,[10] and Friedrich Engels. Beauvoir argues that while Engels, in his The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State (1884), maintained that "the great historical defeat of the female sex" is the result of the invention of bronze and the emergence of private property, his claims are unsupported.[11]

According to Beauvoir, two factors explain the evolution of women's condition: participation in production, and freedom from reproductive slavery.[12] Beauvoir writes that motherhood left woman "riveted to her body", like an animal, and made it possible for men to dominate her and Nature.[13] She describes man's gradual domination of women, starting with the statue of a female Great Goddess found in Susa, and eventually the opinion of ancient Greeks like Pythagoras, who wrote, "There is a good principle that created order, light, and man and a bad principle that created chaos, darkness, and woman." Men succeed in the world by transcendence, but immanence is the lot of women.[14] Beauvoir writes that men oppress women when they seek to perpetuate the family and keep patrimony intact. She compares women's situation in ancient Greece with Rome. In Greece, with exceptions like Sparta where there were no restraints on women's freedom, women were treated almost like slaves. In Rome, because men were still the masters, women enjoyed more rights, but, still discriminated against on the basis of their sex, had only empty freedom.[15]

Discussing Christianity, Beauvoir argues that, with the exception of the German tradition, it and its clergy have served to subordinate women.[16] She also describes prostitution and the changes in dynamics brought about by courtly love that occurred about the twelfth century.[17] Beauvoir describes, from the early fifteenth century, "great Italian ladies and courtesans", and singles out the Spaniard Teresa of Ávila as successfully raising "herself as high as a man".[18] Through the nineteenth century, women's legal status remained unchanged, but individuals (like Marguerite de Navarre) excelled by writing and acting. Some men helped women's status through their works.[19] Beauvoir finds fault with the Napoleonic Code, criticizes Auguste Comte and Honoré de Balzac,[20] and describes Pierre-Joseph Proudhon as an anti-feminist.[21] The Industrial Revolution of the nineteenth century gave women an escape from their homes, but they were paid little for their work.[22] Beauvoir traces the growth of trade unions and participation by women. She examines the spread of birth control methods and the history of abortion.[23] Beauvoir relates the history of women's suffrage,[24] and writes that women like Rosa Luxemburg and Marie Curie "brilliantly demonstrate that it is not women's inferiority that has determined their historical insignificance: It is their historical insignificance that has doomed them to inferiority".[25]

Beauvoir provides a presentation about the "everlasting disappointment" of women,[26] for the most part from a male heterosexual's point of view. She covers female menstruation, virginity, and female sexuality, including copulation, marriage, motherhood, and prostitution. To illustrate man's experience of the "horror of feminine fertility", Beauvoir quotes the British Medical Journal of 1878 in which a member of the British Medical Association writes, "It is an indisputable fact that meat goes bad when touched by menstruating women."[27] She quotes poetry by André Breton, Léopold Sédar Senghor, Michel Leiris, Paul Verlaine, Edgar Allan Poe, Paul Valéry, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and William Shakespeare, along with other novels, philosophers, and films.[28] Beauvoir writes that sexual division is maintained in homosexuality.[26]

Examining the work of Henry de Montherlant, D. H. Lawrence, Paul Claudel, André Breton, and Stendhal, Beauvoir writes that these "examples show that the great collective myths are reflected in each singular writer".[29] "Feminine devotion is demanded as a duty by Montherlant and Lawrence; less arrogant, Claudel, Breton, and Stendhal admire it as a generous choice..."[30] For each of them, the ideal woman is the one who more exactly embodies the Other capable of revealing it to himself. Montherlant seeks pure animality in women; Lawrence demands that she summarizes the female gender in her femininity; Claudel calls her soul-sister; Breton trusts the woman-child; Stendhal is looking for an equal.[31] She finds that woman is "the privileged Other", that Other is defined in the "way the One chooses to posit himself",[32] and writes that, "But the only earthly destiny reserved to the woman equal, child-woman, soul sister, woman-sex, and female animal is always man."[31] Beauvoir writes that, "The absence or insignificance of the female element in a body of work is symptomatic... It loses importance in a period like ours in which each individual's particular problems are of secondary import."[33]

Beauvoir writes that "mystery" is prominent among men's myths about women.[34] She also writes that mystery is not confined by sex to women, but, instead, by situation, and that it pertains to any slave.[35] She thinks it disappeared during the eighteenth century when men, however briefly, considered women to be peers.[36] She quotes Arthur Rimbaud, who writes that, hopefully, one day, women can become fully human beings when man gives her her freedom.[37]

Volume Two

[edit]Presenting a child's life beginning with birth,[38] Beauvoir contrasts a girl's upbringing with a boy's, who at age 3 or 4 is told he is a "little man".[39] A girl is taught to be a woman and her "feminine" destiny is imposed on her by society.[40] She has no innate "maternal instinct".[41] A girl comes to believe in and to worship a male god and to create imaginary adult lovers.[42] The discovery of sex is a "phenomenon as painful as weaning" and she views it with disgust.[43] When she discovers that men, not women, are the masters of the world this "imperiously modifies her consciousness of herself".[44] Beauvoir describes puberty, the beginning of menstruation, and the way girls imagine sex with a man.[45] She relates several ways that girls in their late teens accept their "femininity", which may include running away from home, fascination with the disgusting, following nature, or stealing.[46] Beauvoir describes sexual relations with men, maintaining that the repercussions of the first of these experiences informs a woman's whole life.[47] Beauvoir describes women's sexual relations with women.[48] She writes that "homosexuality is no more a deliberate perversion than a fatal curse".[49]

Beauvoir writes that "to ask two spouses bound by practical, social and moral ties to satisfy each other sexually for their whole lives is pure absurdity".[50] She describes the work of married women, including housecleaning, writing that it is "holding away death but also refusing life".[51] She thinks, "what makes the lot of the wife-servant ungratifying is the division of labor that dooms her wholly to the general and inessential".[52] Beauvoir writes that a woman finds her dignity only in accepting her vassalage which is bed "service" and housework "service".[53] A woman is weaned away from her family and finds only "disappointment" on the day after her wedding.[54] Beauvoir points out various inequalities between a wife and husband who find themselves in a threesome and finds they pass the time not in love but in "conjugal love".[55] She thinks that marriage "almost always destroys woman".[56] She quotes Sophia Tolstoy who wrote in her diary: "you are stuck there forever and there you must sit".[56] Beauvoir thinks marriage is a perverted institution oppressing both men and women.[57]

In Beauvoir's view, abortions performed legally by doctors would have little risk to the mother.[58] She argues that the Catholic Church cannot make the claim that the souls of the unborn would not end up in heaven because of their lack of baptism because that would be contradictory to other Church teachings.[59] She writes that the issue of abortion is not an issue of morality but of "masculine sadism" toward woman.[59] Beauvoir describes pregnancy,[60] which is viewed as both a gift and a curse to woman. In this new creation of a new life the woman loses her self, seeing herself as "no longer anything ... [but] a passive instrument".[61] Beauvoir writes that, "maternal sadomasochism creates guilt feelings for the daughter that will express themselves in sadomasochistic behavior toward her own children, without end",[62] and makes an appeal for socialist child rearing practices.[63]

Beauvoir describes a woman's clothes, her girl friends and her relationships with men.[64] She writes that "marriage, by frustrating women's erotic satisfaction, denies them the freedom and individuality of their feelings, drives them to adultery".[65] Beauvoir describes prostitutes and their relationships with pimps and with other women,[66] as well as hetaeras. In contrast to prostitutes, hetaeras can gain recognition as an individual and if successful can aim higher and be publicly distinguished.[67] Beauvoir writes that women's path to menopause might arouse woman's homosexual feelings (which Beauvoir thinks are latent in most women). When she agrees to grow old she becomes elderly with half of her adult life left to live.[68] A woman might choose to live through her children (often her son) or her grandchildren but she faces "solitude, regret, and ennui".[69] To pass her time she might engage in useless "women's handiwork", watercolors, music or reading, or she might join charitable organizations.[70] While a few rare women are committed to a cause and have an end in mind, Beauvoir concludes that "the highest form of freedom a woman-parasite can have is stoic defiance or skeptical irony".[71]

According to Beauvoir, while a woman knows how to be as active, effective and silent as a man,[72] her situation keeps her being useful, preparing food, clothes, and lodging.[72] She worries because she does not do anything, she complains, she cries, and she may threaten suicide. She protests but doesn't escape her lot.[73] Women demand a Good that is a living Harmony and in which she rests, just because they live. The concept of harmony is one of the keys to the female universe, it implies the perfection of immobility, the immediate justification of each element in the light of the whole, and her passive participation in the totality. In a harmonious way, women thus achieve what men seek in action,[74] as illustrated by Virginia Woolf's Mrs Dalloway and To the Lighthouse, and Katherine Mansfield's magnum opus.[74] Beauvoir thinks it is pointless to try to decide whether a woman is superior or inferior, and that it is obvious that the man's situation is "infinitely preferable".[75] She writes, "for woman there is no other way out than to work for her liberation".[75]

Beauvoir describes narcissistic women, who might find themselves in a mirror and in the theater,[76] and women in and outside marriage: "The day when it will be possible for the woman to love in her strength and not in her weakness, not to escape from herself but to find herself, not out of resignation but to affirm herself, love will become for her as for man the source of life and not a mortal danger."[77] Beauvoir discusses the lives of several women, some of whom developed stigmata.[78] Beauvoir writes that these women may develop a relation "with an unreal: her double or god; or she creates an unreal relation with a real being...".[79] She also mentions women with careers who are able to escape sadism and masochism.[80] A few women have successfully reached a state of equality, and Beauvoir, in a footnote, singles out the example of Clara and Robert Schumann.[81] Beauvoir says that the goals of wives can be overwhelming: as a wife tries to be elegant, a good housekeeper and a good mother.[82] Singled out are "actresses, dancers and singers" who may achieve independence.[83] Among writers, Beauvoir chooses only Emily Brontë, Woolf and ("sometimes") Mary Webb (and she mentions Colette and Mansfield) as among those who have tried to approach nature "in its inhuman freedom". Beauvoir then says that women don't "challenge the human condition" and that in comparison to the few "greats", a woman comes out as "mediocre" and will continue at that level for quite some time.[84] A woman could not have been Vincent van Gogh or Franz Kafka. Beauvoir thinks that perhaps, of all women, only Saint Teresa lived her life for herself.[85] She says it is "high time" a woman "be left to take her own chances".[86]

In her conclusion, Beauvoir looks forward to a future when women and men are equals, something the "Soviet revolution promised" but did not ever deliver.[87] She concludes that, "to carry off this supreme victory, men and women must, among other things and beyond their natural differentiations, unequivocally affirm their brotherhood."[88]

Reception and influence

[edit]The first French publication of The Second Sex sold around 22,000 copies in a week.[89] It has since been translated into 40 languages.[90] The Vatican placed the book on its List of Prohibited Books.[7] The sex researcher Alfred Kinsey was critical of The Second Sex, holding that while it was interesting as a work of literature, it was of no value to science.[91] In 1960, Beauvoir wrote that The Second Sex was an attempt to explain "why a woman's situation, still, even today, prevents her from exploring the world's basic problems."[92] In a 1974 interview, she remembered that "Camus was furious; he reacted with typical Mediterranean machismo, saying I had ridiculed the French male. Professors hurled the book across the room. People sniggered at me in restaurants. The fact [that] I had spoken about female sexuality was absolutely scandalous at the time. Men kept drawing attention to the vulgarity of the book, essentially because they were furious at what the book was suggesting—equality between the sexes".[93] The attack on psychoanalysis in The Second Sex helped to inspire subsequent feminist arguments against psychoanalysis, including those of Betty Friedan's The Feminine Mystique (1963), Kate Millett's Sexual Politics (1969), and Germaine Greer's The Female Eunuch (1970).[94] Millett commented in 1989 that she did not realize the extent to which she was influenced by Beauvoir when she wrote Sexual Politics.[95]

Philosopher Judith Butler argues that Beauvoir's formulation that "One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman" distinguishes the terms "sex" and "gender". Borde and Malovany-Chevallier, in their complete English version, translated this formulation as "One is not born, but rather becomes, woman" because in this context (one of many different usages of "woman" in the book), the word is used by Beauvoir to mean woman as a construct or an idea, rather than woman as an individual or one of a group. Butler writes that the book suggests that "gender" is an aspect of identity which is "gradually acquired". Butler sees The Second Sex as potentially providing a radical understanding of gender.[96]

Biographer Deirdre Bair, writing in her "Introduction to the Vintage Edition" in 1989, relates that "one of the most sustained criticisms" has been that Beauvoir is "guilty of unconscious misogyny", that she separated herself from women while writing about them.[97] Bair writes that French writer Francis Jeanson and British poet Stevie Smith made similar criticisms: in Smith's words, "She has written an enormous book about women and it is soon clear that she does not like them, nor does she like being a woman."[98] Bair also quotes British scholar C. B. Radford's view that Beauvoir was "guilty of painting women in her own colors" because The Second Sex is "primarily a middle-class document, so distorted by autobiographical influences that the individual problems of the writer herself may assume an exaggerated importance in her discussion of femininity.[98]

American theorist David M. Halperin criticizes Beauvoir's idealizing portrayal of sexual relations between women in The Second Sex.[99] Critic Camille Paglia praised The Second Sex, calling it "brilliant" and "the supreme work of modern feminism." Paglia writes that most modern feminists are merely "repeating, amplifying or qualifying" The Second Sex without realising their debt to it.[100] In Free Women, Free Men (2017) Paglia writes that as a sixteen-year-old, she was "stunned by de Beauvoir's imperious, authoritative tone and ambitious sweep through space and time", which helped inspire her to write her work of literary criticism Sexual Personae (1990).[101]

Censorship

[edit]The Spanish-language translation of The Second Sex (printed in Argentina) was banned in Francoist Spain in 1955. Spanish feminists smuggled in copies of the book and circulated it in secret. A full Castilian Spanish translation of The Second Sex was published in 1998.[102]

The Catholic Church's Vatican-based leadership condemned The Second Sex and added the book in its list of prohibited books, known as Index Librorum Prohibitorum. The book remained banned until the policy of prohibition itself was abolished in 1966.

Cultural repercussions

[edit]The rise of second wave feminism in the United States spawned by Betty Friedan’s book, The Feminine Mystique, which was inspired by Simone de Beauvoir’s, The Second Sex, took significantly longer to reach and impact the lives of European women. Even though The Second Sex was published in 1949 and Feminine Mystique was published in 1963, the French were concerned that expanding equality to include matters of the family was detrimental to French morals. In 1966, abortion in Europe was still illegal and contraception was extremely difficult to access. Many were afraid that legalization would "take from men 'the proud consciousness of their virility' and make women 'no more than objects of sterile voluptuousness'".[103] The French Parliament in 1967 decided to legalize contraception but only under strict qualifications.

Social feminists then went further to claim that women “were fundamentally different from men in psychology and in physiology…”[103] and stressed gender differences rather than simply equality, demanding that women have the right of choice to stay home and raise a family, if they so desired, by issue of a financial allowance, advocated by the Catholic church, or to go into the workforce and have assistance with childcare through government mandated programs, such as nationally funded daycare facilities and parental leave. The historical context of the times was a belief that "a society cut to the measure of men ill served women and harmed the overall interests of society".[103] As a result of this push for public programs, European women became more involved in politics and by the 1990s held six to seven times more legislative seats than the United States, enabling them to influence the process in support of programs for women and children.[103]

Translations

[edit]Many commentators have pointed out that the 1953 English translation of The Second Sex by H. M. Parshley, frequently reissued, is poor.[104] A reviewer from The New York Times described the zoologist hired to do the translation as having "a college undergraduate's knowledge of French."[7] The delicate vocabulary of philosophical concepts is frequently mistranslated, and great swaths of the text have been excised.[105] The English publication rights to the book are owned by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc and although the publishers had been made aware of the problems with the English text, they long stated that there was really no need for a new translation,[104] even though Beauvoir herself explicitly requested one in a 1985 interview: "I would like very much for another translation of The Second Sex to be done, one that is much more faithful; more complete and more faithful."[106]

The publishers gave in to those requests, and commissioned a new translation to Constance Borde and Sheila Malovany-Chevallier.[107] The result, published in November 2009,[108] has met with generally positive reviews from literary critics, who credit Borde and Malovany-Chevallier with having diligently restored the sections of the text missing from the Parshley edition, as well as correcting many of its mistakes.[109][110][111][112]

Other reviewers, however, including Toril Moi, one of the most vociferous critics of the original 1953 translation, are critical of the new edition, voicing concerns with its style, syntax and philosophical and syntactic integrity.[7][113][114]

The New York Times reviewer cites some confused English in the new edition where Parshley's version was smoother, saying, "Should we rejoice that this first unabridged edition of 'The Second Sex' appears in a new translation? I, for one, do not."[7]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ de Beauvoir, Simone (1949). Le deuxième sexe [The Second Sex]. NRF essais (in French). Vol. 1, Les faits et les mythes [Facts and Myths]. Gallimard. ISBN 9782070205134.

- ^ de Beauvoir, Simone (1949). Le deuxième sexe. NRF essais (in French). Vol. 2 L'expérience vécue [Experience]. Gallimard. ISBN 9782070205141. OCLC 489616596.

- ^ Thurman, Judith (2011). The Second Sex. New York: Random House. p. 13.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. Copyright page.

- ^ Appignanesi 2005, p. 82.

- ^ "Reception of The Second Sex in Europe". Encyclopédie d’histoire numérique de l'Europe. Retrieved 2022-08-14.

- ^ a b c d e du Plessix Gray, Francine (May 27, 2010), "Dispatches From the Other", The New York Times, retrieved October 24, 2011

- ^ de Beauvoir, Simone (1953). The Second Sex. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. xv–xxix. ISBN 9780394444154.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 46.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 59.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 63–64.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 139.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 75.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, pp. 79, 89, 84.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, pp. 96, 100, 101, 103.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, pp. 104–106, 117.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, pp. 108, 112–114.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 118, "She brilliantly shows that a woman can raise herself as high as a man when, by astonishing chance, a man's possibilities are granted to her."

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, pp. 118, 122, 123.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, pp. 127–129.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 131.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 132.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, pp. 133–135, 137–139.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, pp. 140–148.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 151.

- ^ a b Beauvoir 2009, p. 213.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, pp. 168, 170.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, pp. 175, 176, 191, 192, 196, 197, 201, 204.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 261.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, pp. 264–265.

- ^ a b Beauvoir 2009, p. 264.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 262.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 265.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 268.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 271.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 273.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 274.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 284.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, pp. 285–286.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, pp. 294–295.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 296.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, pp. 304–305, 306–308.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, pp. 315, 318.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 301.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, pp. 320–330, 333–336.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, pp. 366, 368, 374, 367–368.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 383.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 416.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 436.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 466.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, pp. 470–478.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 481.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 485.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, pp. 485–486.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, pp. 497, 510.

- ^ a b Beauvoir 2009, p. 518.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 521.

- ^ Beauvoir 1971, p. 458.

- ^ a b Beauvoir 1971, p. 486.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, pp. 524–533, 534–550.

- ^ Beauvoir 1971, p. 495.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 567.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 568.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, pp. 571–581, 584–588, 589–591, 592–598.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 592.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, pp. 605, 607–610.

- ^ Beauvoir 1971, p. 565.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, pp. 619, 622, 626.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, pp. 627, 632, 633.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, pp. 634–636.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, pp. 636–637.

- ^ a b Beauvoir 2009, p. 644.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, pp. 645, 647, 648, 649.

- ^ a b Beauvoir 2009, p. 658.

- ^ a b Beauvoir 2009, p. 664.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, pp. 668–670, 676.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 708.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, pp. 713, 714–715, 716.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 717.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, pp. 731–732.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 733.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 734.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 741.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 748.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 750.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 751.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 760.

- ^ Beauvoir 2009, p. 766.

- ^ Rossi, Alice S. (19 May 1988). The Feminist Papers: From Adams to de Beauvoir. Boston: Northeastern University Press. p. 674. ISBN 978-1-55553-028-0.

- ^ The Book Depository. "The Second Sex (Paperback)". AbeBooks Inc. Retrieved October 21, 2017.

- ^ Pomeroy, Wardell (1982). Dr. Kinsey and the Institute for Sex Research. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 279. ISBN 0-300-02801-6.

- ^ Beauvoir, Simone de (1962) [1960]. The Prime of Life. Translated by Green, Peter. Cleveland: The World Publishing Company. p. 38. LCCN 62009051.

- ^ Moorehead, Caroline (2 June 1974). "A talk with Simone de Beauvoir". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 August 2023.

- ^ Webster, Richard (2005). Why Freud Was Wrong: Sin, Science and Psychoanalysis. Oxford: The Orwell Press. p. 22. ISBN 0-9515922-5-4.

- ^ Forster, Penny; Sutton, Imogen (1989). Daughters of de Beauvoir. London: The Women's Press, Ltd. p. 23. ISBN 0-7043-5044-0.

- ^ Butler, Judith, "Sex and Gender in Simone de Beauvoir's Second Sex" in Yale French Studies, No. 72 (1986), pp. 35–49.

- ^ Bair 1989, p. xiii.

- ^ a b Bair 1989, p. xiv.

- ^ Halperin, David M. (1990). One Hundred Years of Homosexuality: And Other Essays on Greek Love. New York: Routledge. pp. 136, 138. ISBN 0-415-90097-2.

- ^ Paglia, Camille (1993). Sex, Art, and American Culture: Essays. New York: Penguin Books. pp. 112, 243. ISBN 0-14-017209-2.

- ^ Paglia, Camille (2017). Free Women, Free Men: Sex, Gender, Feminism. New York: Pantheon Books. p. xiii. ISBN 978-0-375-42477-9.

- ^ Gutiérrez, Lucía Pintado and Castillo Villanueva, Alicia (eds.) (2019). New Approaches to Translation, Conflict and Memory : Narratives of the Spanish Civil War and the Dictatorship. Cham : Springer International Publishing : Palgrave Macmillan. p. 96 ISBN 978-3-030-00698-3

- ^ a b c d Hunt, Michael H. (2014). The World Transformed: 1945 to the Present. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 226–227. ISBN 978-0-19-937234-8.

- ^ a b Moi, Toril (2002), "While we wait: The English translation of The Second Sex" in Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society vol. 27, no. 4, pp. 1005–1035.

- ^ Simons, Margaret, "The Silencing of Simone de Beauvoir: Guess What's Missing from The Second Sex" in Beauvoir and The Second Sex (1999), pp. 61–71.

- ^ Simons, Margaret, "Beauvoir Interview (1985)", in Beauvoir and The Second Sex (1999), pp. 93–94.

- ^ Moi, Toril (January 12, 2008), "It changed my life!", The Guardian.

- ^ London: Jonathan Cape, 2009. ISBN 978-0-224-07859-7.

- ^ di Giovanni, Janine, "The Second Sex[dead link]", in The Times (London).

- ^ Cusk, Rachel (December 12, 2009), "Shakespeare's Daughters", in The Guardian.

- ^ Crowe, Catriona (December 19, 2009), "Second can be the best", in The Irish Times.

- ^ Smith, Joan (December 18, 2009), "The Second Sex, By Simone de Beauvoir trans. Constance Borde & Sheila Malovany-Chevallier", in The Independent (London).

- ^ Moi, Toril (2010). "The Adulteress Wife". London Review of Books. 32 (3): 3–6. Archived from the original on 2021-08-25. Retrieved September 6, 2012.

- ^ Goldberg, Michelle. "The Second Sex". Barnes and Noble Review. Retrieved September 6, 2012.

References

[edit]- Appignanesi, Lisa (2005). Simone de Beauvoir. London: Haus. ISBN 1-904950-09-4.

- Bauer, Nancy (2006) [2004]. "Must We Read Simone de Beauvoir?". In Grosholz, Emily R. (ed.). The Legacy of Simone de Beauvoir. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-926536-4.

- Beauvoir, Simone (1971). The Second Sex. Alfred A. Knopf.

- Bair, Deirdre (1989) [Translation first published 1952]. "Introduction to the Vintage Edition". The Second Sex. By Beauvoir, Simone de. Trans. H. M. Parshley. Vintage Books (Random House). ISBN 0-679-72451-6.

- Beauvoir, Simone de (2002). The Second Sex (Svensk upplaga). p. 325.

- Beauvoir, Simone de (2009) [1949]. The Second Sex. Trans. Constance Borde and Sheila Malovany-Chevallier. Random House: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-307-26556-2.

External links

[edit]- Cusk, Rachel (December 11, 2009). "Shakespeare's daughters". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media.

- "Second can be the best". The Irish Times. December 12, 2009.

- Smith, Joan (December 18, 2009). "The Second Sex, By Simone de Beauvoir trans. Constance Borde & Sheila Malovany-Chevallier". The Independent.

- "'The Second Sex' by Simone de Beauvoir". Marxists Internet Archive. (Free English translation of a small part of the book)

- Zuckerman, Laurel (March 23, 2011). "The Second Sex: a talk with Constance Borde and Sheila Malovany Chevalier". laurelzuckerman.com.

- Radio National (November 16, 2011). "Translating the 'Second Sex". ABC: The Book Show. ABC.net.au.

- Udovitch, Mim (December 6, 1988). "Hot and Epistolary: 'Letters to Nelson Algren', by Simone de Beauvoir". The New York Times.

- Menand, Louis (September 26, 2005). "Stand By Your Man: The strange liaison of Sartre and Beauvoir (Book review of the republished The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir)". The New Yorker.