Shanawdithit

Shanawdithit | |

|---|---|

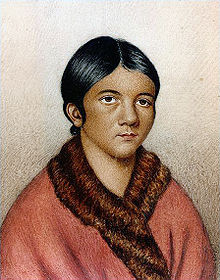

A beothuk woman (ca. 1841) believed to be Shanawdithit, though possibly a reproduction of a portrait of Demasduit. | |

| Born | Shanawdithit ca. 1801 |

| Died | June 6, 1829 (aged 27–28) |

| Cause of death | Tuberculosis |

| Other names | Shawnadithit, Shawnawdithit, Nancy April |

| Known for | last Beothuk |

Shanawdithit (ca. 1801 – June 6, 1829), also noted as Shawnadithit, Shawnawdithit, Nancy April and Nancy Shanawdithit, was the last known living member of the Beothuk people, who inhabited Newfoundland, Canada. Remembered for her contributions to the historical understanding of Beothuk culture, including drawings depicting interactions with European settlers, Shanawdithit died of tuberculosis in St. John's, Newfoundland on June 6, 1829.[1]

Early life with the Beothuk

[edit]Shanawdithit was born near a large lake on the island of Newfoundland in about 1801.[2]: 233 At the time the Beothuk population was dwindling, their traditional way of life becoming increasingly unsustainable in the face of encroachment from both European colonial settlements and other Indigenous peoples, as well as infectious diseases from Europe such as smallpox against which they had little or no immunity. The Beothuks were also slowly being cut off from the sea, one of their food sources.

During this period, most Indigenous nations in the Americas tolerated some level of contact with European settlers. The resulting trade generally afforded them the opportunity to maintain at least a minimal standard of living. In contrast, Beothuks had long avoided this sort of interaction with outsiders. Trappers and furriers regarded the Beothuks as thieves and would sometimes attack them. As a child, Shanawdithit was shot by a white trapper while washing venison in a river. She suffered from the injury for some time, but recovered.[2]: 233–234

In 1819, Shanawdithit's aunt Demasduit was captured by a party of settlers led by John Peyton Jr. and the few remaining Beothuks fled. In the spring of 1823, Shanawdithit lost her father, who died after falling through ice. Most of her extended family had already died from a combination of starvation, illness, exposure and attacks from European settlers. In April 1823, Shanawdithit, along with her mother, Doodebewshet, and her sister, whose Beothuk name is unknown, encountered trappers while searching for food in the Badger Bay area.[3][4] William Cull and the three women were taken to St. John's, where Shanawdithit's mother and sister died of tuberculosis.

Later life in the Newfoundland Colony

[edit]

The settlers in the Newfoundland Colony renamed Shanawdithit "Nancy April" after the month in which she was captured, taking her to Exploits Island where she worked as a servant in the Peyton household and learned some English. The colonial government hoped she would become a bridge to her people, but she refused to leave with any expedition, saying the Beothuks would kill anyone who had been with the Europeans, as a kind of religious sacrifice and redemption for those who had been killed.[5]

In September 1828, Shanawdithit was relocated to St. John's to live in the household of William Eppes Cormack, the founder of the Beothuk Institution.[6] A Scottish emigrant, Newfoundland entrepreneur and philanthropist, he recorded much of what Shanawdithit told him about her people and added notes to her drawings. Shanawdithit stayed in Cormack's care until early 1829 when he left Newfoundland. Cormack returned to Great Britain where he stayed for some time in Liverpool with John McGregor, a Scotsman whom he had known in Canada, sharing many of his materials on the Beothuks.[5]

Following Cormack's departure, Shanawdithit was cared for by the attorney general, James Simms.[6] She spent the last nine months of her life at his home, having been in frail health for a number of years. William Carson tended her, but in 1829, Shanawdithit died in a St. John's hospital after her long fight with tuberculosis. In addition to an obituary announcement in a local St. John's newspaper on June 12, 1829, the death of Shanawdithit was reported in the London Times on September 14, 1829. The announcement noted that Shanawdithit "exhibited extraordinary strong natural talents" and identified the Beothuk as "an anomaly in the history of man" for not establishing or maintaining relationships with European settlers or other Indigenous peoples.[7]: 231 [8]

After her death

[edit]After Shanawdithit's death Carson performed a postmortem and noted peculiarities with the parietal bone of the skull, eventually sending it to the Royal College of Physicians in London for study.[9]: 220, 524 Shanawdithit's remains were buried in the graveyard of St. Mary the Virgin Church on the south side of St. John's. In 1938, the Royal College of Physicians gave her skull to the Royal College of Surgeons. It was lost in the German Blitz bombing of London in World War II.[9]: 220

Meanwhile, in 1903, the church graveyard had been lost to railway construction. The church was torn down in 1963. A monument on the site reads: "This monument marks the site of the Parish Church of St. Mary the Virgin during the period 1859–1963. Fishermen and sailors from many ports found a spiritual haven within its hallowed walls. Near this spot is the burying place of Nancy Shanawdithit, very probably the last of the Beothuks, who died on June 6, 1829".[10]

Legacy

[edit]

Shanawdithit played a vital role in documenting what little is known about the Beothuk people. Researcher Ingeborg Marshall has argued that a valid understanding of Beothuk history and culture is affected directly by how and by whom historical records were created, pointing to the ethnocentric nature of European accounts which positioned native populations as inherently inferior. She notes that without Shanawdithit's accounts of her nation's later life, the Beothuk voice is nearly absent from historical accounts.[9]: 8

Shanawdithit was recognized as a National Historic Person in 2000.[2]: 236 [11] The announcement coincided with the installation of a statue depicting Shanawdithit by Gerald Squires, titled The Spirit of the Beothuk, at the Beothuk Interpretation Centre near Boyd's Cove.[12][13] In 2007 a plaque commemorating her life was unveiled at St. John's Bannerman Park acknowledging her contributions to the historical accounts of encounters between the Beothuk and European settlers, and the apprehension of her aunt, Demasduit, by John Peyton Jr.[14]

Shanawdithit is widely known among Newfoundlanders. In 1851, a local paper, the Newfoundlander, called her "a princess of Terra Nova". In 1999, The Telegram readers voted her the most notable Aboriginal person of the past 1,000 years. She had 57% of the votes.[citation needed]

Her story was the basis for the 2023 College of the North Atlantic Digital Filmmaking program's intersession film project.[15][16][17]

See also

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- Polack, Fiona (2013). "Reading Shanawdithit's Drawings: Transcultural texts in the North American colonial world". Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History. 14 (3). doi:10.1353/cch.2013.0035. S2CID 161542958.

References

[edit]- ^ Ivan Semeniuk (October 13, 2017). "DNA deepens mystery of lost Beothuk people in Newfoundland". Globe and Mail. p. A1.

- ^ a b c Forster, Merna (2004). "A Canadian Tragedy: Shanawdithit ca. 1801-1829". 100 Canadian heroines : famous and forgotten faces. Toronto: Dundurn Group. ISBN 9781550025149. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ "Disappearance of the Beothuk". Heritage Newfoundland & Labrador. July 2013. Archived from the original on 23 January 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ Marshall, Ingeborg C. L. (2006). "Shanawdithit, or Nance, Nancy April". In Hallowell, Gerald (ed.). The Oxford companion to Canadian history. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN 9780195415599. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ a b Anonymous (James McGregor), "Shaa-naan-dithit, or The Last of The Boëothics", Fraser's Magazine for Town and Country, Vol. XIII, No LXXV (March 1836): 316-323 (Rpt. Toronto: Canadiana House, 1969), Memorial University of Labrador & Newfoundland Website, accessed 16 February 2009

- ^ a b Pastore, Ralph T.; Story, G. M. (1987). "Shanawdithit". Dictionary of Canadian Biography Volume VI (1821-1835). University of Toronto/Université Laval. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ Howley, James Patrick (1915). The Beothucks or Red Indians : the aboriginal inhabitants of Newfoundland. Cambridge: University Press. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ "Died, at St. John's, Newfoundland, on the 6th of June last, in the 29th year of her age, Shawnawdithit, supposed". Times. No. 14018. [London, England]. 14 September 1829. p. 5.

- ^ a b c Marshall, Ingeborg (1998). A history and ethnography of the Beothuk. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 9780773517745. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ "Biography: Shanawdithit". Discovery Collegiate High School Bonavista, Newfoundland. K-12 school Web pages in Newfoundland and Labrador. Archived from the original on 2008-12-30. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- ^ "Shanawdithit National Historic Person". Park Canada. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ Gibbs, Graham (2016). Five Ages of Canada: A History From Our First Peoples to Confederation. FriesenPress. pp. 33–34. ISBN 9781460283110. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ "Muse for Gerald Squires sculpture mourns artist's passing". CBC News. 6 October 2015. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ "Last of Beothuk honoured in new monument". CBC News. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ "CNA's 2023 Final Film Festival".

- ^ "Shanawdithit: A Beothuk Story". IMDb.

- ^ "Film Festival 2023 reflects on Indigenous themes". NationTalk. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

External links

[edit]- Appendix: "Letter from the Lordbishop of Nova Scotia", Society for Propagation of the Gospel (SPG) Annual Report 1827. London: S.P.G. and C. & J. Rivington, 1828: 85-88, Memorial University of Newfoundland & Labrador Website

- 1800s births

- 1829 deaths

- 19th-century deaths from tuberculosis

- 19th-century First Nations people

- Beothuk people

- First Nations artists

- Last known speakers of a Native American language

- Newfoundland Colony people

- People from Newfoundland (island)

- Persons of National Historic Significance (Canada)

- Tuberculosis deaths in Newfoundland and Labrador

- First Nations women

- 19th-century women artists

- Last known members of an Indigenous people

- Women cartographers