Powder Ridge Rock Festival

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2008) |

| Powder Ridge Rock Festival | |

|---|---|

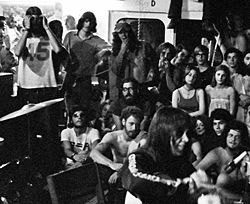

Melanie Safka was the only artist ignoring the court injunction banning the festival; she performed on an improvised stage powered by Mister Softee trucks. | |

| Genre | Rock music |

| Dates | July 31, August 1 and August 2, 1970 |

| Location(s) | Powder Ridge Ski Area in Middlefield, Connecticut |

| Years active | 1970 (cancelled) |

| Attendance | 30,000 |

The Powder Ridge Rock Festival was scheduled to be held July 31, August 1 and August 2, 1970, at Powder Ridge Ski Area in Middlefield, Connecticut. A legal injunction forced the event to be canceled, keeping the musicians away; but a crowd of 30,000 attendees[1] arrived anyway, to find no food, no entertainment, no adequate plumbing, and at least seventy drug dealers. William Manchester wrote: "Powder Ridge was an accident waiting to happen, and it happened."[1] Volunteer doctor William Abruzzi declared a drug "crisis" on August 1, saying "Woodstock was a pale pot scene. This is a heavy hallucinogens scene."[2]

History

[edit]Announcement and preparations

[edit]Tickets were sold by mail at a price of $20 (the equivalent of $144.92 in 2022 dollars) for the whole weekend. The announced line-up of musicians included:

- Day 1: Eric Burdon & War, Sly and the Family Stone, Delaney & Bonnie, Fleetwood Mac, Melanie, Mountain, J.F. Murphy and Free Flowing Salt, Allan Nichols, James Taylor

- Day 2: Joe Cocker, Allman Brothers, Cactus, Little Richard, Van Morrison, Rhinoceros, Ten Wheel Drive, Jethro Tull, Tony Williams Lifetime, Zephyr

- Day 3: Janis Joplin, Chuck Berry, Bloodrock, Savoy Brown, Chicken Shack, Grand Funk Railroad, Richie Havens, John B. Sebastian, Spirit, Ten Years After

Lawsuit

[edit]Powder Ridge was anticipated to be a significant historical music event, similar to the previous year's Woodstock festival.[3] In the year following Woodstock, however, the reputation of music festivals associated with the hippie movement had become increasingly negative following the Altamont festival and went into "a long spiral of decline".[4] Thirty of the forty-eight major festivals planned for 1970 were cancelled, usually due to swiftly materializing local opposition.[citation needed] Powder Ridge, however, made national news because of the arrival of tens of thousands of ticketholders despite the event's cancellation. The New York Times followed its progress in about thirty articles before, during, and after the event.[citation needed]

Middlefield residents, worried about the impact of the crowd on their small town, obtained an injunction against the festival just days before it began.[3]

When the owner of the ski resort tried to contact the promoters to tell them of the injunction, they could not be found.[citation needed]

Attendees arrive anyway

[edit]Local authorities posted warning signs on every highway leading to Middlefield: "Festival Prohibited, turn back".[citation needed]

By 1970, rock festivals were regarded as having a political dimension. Carol Brightman wrote that "Rock shows... such as the Powder Ridge concert... were increasingly being covered by the national media as civil events, one step removed from street demonstrations."[5]

Promoters, however, kept hinting that there was still a chance that the concert would be held: "It's a total wait and see thing," a spokesman said and, after all, Woodstock had almost been cancelled too.[6]

Approximately 30,000 people came to the site for the weekend. Most of the musicians, however, did not show up. Only Melanie and a few local bands actually performed during the three-day weekend.[3] One of these local bands was "The Mustard Family" who, in the dark of night, hauled their instruments and equipment into the festival, by back roads and trails, and performed for the enthusiastic crowd.[citation needed] The official poster for the festival lists New York band, Haystacks Balboa, as the special opening act on Thursday night. The band's equipment was stopped by the authorities and the musicians gathered at a local cafe to await word as to their performance. After long negotiations, the band's manager advised the band to return home, there was to be no performance.[citation needed]

The festival scene

[edit]Drugs were openly sold and commonly consumed at the festival.[7] Rock doctor William Abruzzi (also at Woodstock) was there to treat bad LSD trips, and said there were more bad trips at Powder Ridge per capita than at any other music festival he'd ever worked.[citation needed] He attributed some of the problems to the barrels of "electric water" that were available for free public consumption; people were invited to drop donations of drugs into these barrels, creating drug cocktails of unknown strength and composition.[citation needed]

William Manchester writes:

One of the more sensational scenes, attested to by several witnesses, occurred in a small wood near some homes. A boy and a girl, both naked and approaching from different directions, met under the trees. On impulse they suddenly embraced. She dropped to her knees, he mounted her from behind, and after he had achieved his climax they parted—apparently without exchanging a word.[1]

According to The New York Times, observers who had been at both Woodstock and Powder Ridge were struck by the contrasting moods of the two festivals:

The gentle euphoria—the grins, small smiles, and exchanged "V" signals— of people milling through the muddy fields of Bethel seemed to be missing at Powder Ridge. Instead, last night and this morning, the major pastime here was often shuffling walks along paved roads by grim-faced young men and women who looked remarkably similar to old people moving slowly along the boardwalks of the Rockaways or Atlantic City.[2]

In his autobiography, Nothing's Sacred, comedian Lewis Black claims to have attended the festival with some friends. Black explains in depth his activities of the weekend, including drug experimentation, failing at his appointed parking attendant job, and the downturn the concert took after a fiery speech from a Black Panther of the militant New Haven, Connecticut contingent, which happened to coincide with a thunderstorm. Black theorizes that under the effects of hallucinogens, many attendees probably thought that the Black Panther was actually causing the storm, and many began to experience bad trips.

Aftermath

[edit]Although the promoters of the festival announced plans to reschedule the event for another location, no such plans ever came through, and no refunds were ever issued to the ticket buyers.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Estimates vary from 15,000 to 50,000. "30,000" is from a New York Times article, July 31, 1970 p. 24

References

[edit]- ^ a b William Manchester, 1972, The Glory and the Dream: A Narrative History of America 1932-1972, pp. 1212-1213. Bantam Books.

- ^ a b "Drug Peril Eases at Powder Ridge". The New York Times. August 2, 1970. p. 58, § 1. Retrieved 2021-08-30.

- ^ a b c Wollschlager, Mike. "Powder Ridge Rock Festival: The greatest show that never was". CTInsider.com. Hearst Media Services Connecticut. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ Bill Mankin, We Can All Join In: How Rock Festivals Helped Change America. Like the Dew. 2012.

- ^ Carol Brightman, 1998, Sweet Chaos : The Grateful Dead's American Adventure; Clarkson Potter, ISBN 0-517-59448-X.

- ^ Plenty of Sex and Drugs, But No Rock ´n´ Roll, 2005 Hartford Advocate article.

- ^ Darnton, John (August 1, 1970). "Youths at Powder Ridge Maintain Festival Atmosphere". The New York Times. Retrieved 2021-08-30.