St Albans Cathedral

| St Albans Cathedral | |

|---|---|

| Cathedral and Abbey Church of St Alban | |

St Albans Abbey viewed from the south west | |

| 51°45′02″N 0°20′32″W / 51.750556°N 0.342222°W | |

| Location | St Albans, Hertfordshire AL1 1BY |

| Country | |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Previous denomination | Roman Catholic |

| Tradition | Liberal Catholic |

| Website | stalbanscathedral.org |

| History | |

| Status | Active |

| Founded | 793 |

| Dedication | St Alban |

| Consecrated | 28 December 1115 |

| Cult(s) present | Saint Alban |

| Relics held | Saints Alban, Amphibalus |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Cathedral |

| Heritage designation | Grade I listed[1] |

| Designated | 8 May 1950 |

| Style | Norman, Romanesque, Gothic |

| Years built | 1077–1893 |

| Groundbreaking | 1005 |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 167.8 metres (551 ft) |

| Nave length | 85 metres (279 ft)[2] |

| Nave width | 23 metres (75 ft) |

| Width across transepts | 58.5 metres (192 ft)[3] |

| Height | 43.9 metres (144 ft) |

| Nave height | 20.2 metres (66 ft)[4] |

| Number of towers | 1 |

| Tower height | 43.9 metres (144 ft) |

| Bells | 12 (2010) |

| Tenor bell weight | 21-0-19 (1075kg) |

| Administration | |

| Province | Canterbury |

| Diocese | St Albans (since 1877) |

| Clergy | |

| Bishop(s) | Alan Smith |

| Dean | Jo Kelly-Moore |

| Subdean | vacant |

| Precentor | Vanessa Jefferson (Minor Canon) |

| Canon Chancellor | Kevin Walton |

| Canon(s) | Tim Bull (Dir. Ministry) Tim Lomax (Dir. of Mission) 1 vacancy (Sub-Dean) |

| Chaplain(s) | Calum Zuckert (Minor Canon & Youth Chaplain) |

| Laity | |

| Director of music | William Fox |

| Organist(s) | Tom Winpenny |

| Official name | St Albans Abbey, Site of Conventual Buildings |

| Reference no. | 1003526 |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Official name | Abbey Church of St Alban |

| Designated | 8 May 1950 |

| Reference no. | 1103163 |

St Albans Cathedral, officially the Cathedral and Abbey Church of St Alban,[5] also known as "the Abbey", is a Church of England cathedral in St Albans, England.

Much of its architecture dates from Norman times. It ceased to be an abbey following its dissolution in the 16th century and became a cathedral in 1877. Although legally a cathedral church, it differs in certain particulars from most other cathedrals in England, being also used as a parish church, of which the dean is rector with the same powers, responsibilities and duties as those of any other parish.[6] At 85 metres long, it has the longest nave of any cathedral in England.[2]

Probably founded in the 8th century, the present building is Norman or Romanesque architecture of the 11th century, with Gothic and 19th-century additions.

Britain's first Christian martyr

[edit]According to Bede, whose account of the saint's life is the most elaborate, Alban lived in Verulamium, some time during the 3rd or 4th centuries. At that time Christians began to suffer "cruel persecution".[7] The legend proceeds with Alban meeting a Christian priest (known as Amphibalus) fleeing from "persecutors", and sheltering him in his house for a number of days. Alban was so impressed with the priest's faith and piety that he soon converted to Christianity. Eventually Roman soldiers came to seize the priest, but Alban put on his cloak and presented himself to the soldiers in place of his guest. Alban was brought before a judge and was sentenced to beheading.[7] As he was led to execution, he came to a fast flowing river, commonly believed to be the River Ver, crossed it and went about 500 paces to a gently sloping hill overlooking a beautiful plain[7] When he reached the summit he began to thirst and prayed that God would give him drink, whereupon water sprang up at his feet. It was at this place that his head was struck off. Immediately after one of the executioners delivered the fatal stroke, his eyes fell out and dropped to the ground alongside Alban's head.[7] Later versions of the tale say that Alban's head rolled downhill and that a well gushed up where it stopped.[8] St Albans Cathedral stands near the supposed site of Alban's martyrdom, and references to the spontaneous well are extant in local place names. The nearby river was called Halywell (Middle English for 'Holy Well') in the medieval era, and the road up to Holmhurst Hill on which the Abbey now stands is now called Holywell Hill but has been called Halliwell Street and other variations at least since the 13th century.[8] The remains of a well structure have been found at the bottom of Holywell Hill. However, this well is thought to date from no earlier than the 19th century.[9]

The date of Alban's execution has never been firmly established. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle lists the year 283,[10] but Bede places it in 305. Original sources and modern historians such as William Hugh Clifford Frend and Charles Thomas indicate the period of 251–259 (under the persecutors Decius or Valerian) as more likely.

The tomb of St Amphibalus is in the cathedral.[11]

History of the abbey and cathedral

[edit]

A memoria over the execution point holding the remains of Alban existed at the site from the mid-4th century (possibly earlier); Bede mentions a church and Gildas a shrine. Bishop Germanus of Auxerre visited in 429.[12] The style of this structure is unknown; the 13th-century chronicler Matthew Paris (see below) said the Saxons destroyed the building in 586.

Saxon buildings

[edit]Offa II of Mercia, is said to have founded a double monastery at St Albans in 793. It followed the Benedictine rule.[13] The Abbey was built on Holmhurst Hill—now Holywell Hill—across the River Ver from the ruins of Verulamium. Again there is no information to the form of the first abbey.

Abbot Ulsinus founded St Albans Market outside of the Waxhouse Gate, on what is now Market Place, in c. 860 to generate income for the Abbey and to form the centre of a new town.[14][15][16]

The Abbey was probably sacked by the Danes around 890 and, despite Paris's claims, the office of abbot remained empty from around 920 until the 970s when the efforts of Dunstan reached the town.

There was an intention to rebuild the Abbey in 1005 when Abbot Ealdred was licensed to remove building material from Verulamium. With the town resting on clay and chalk, the only tough stone is flint. This was used with a lime mortar and then either plastered over or left bare. With the great quantities of brick, tile and other stone in Verulamium, the Roman site became a prime source of building material for the Abbey and other projects in the area.[17] Sections demanding worked stone used Lincolnshire limestone (Barnack stone) from Verulamium; later worked stones include Totternhoe freestone from Bedfordshire, Purbeck marble, and different limestones (Ancaster, Chilmark, Clipsham, etc.).

Renewed Viking raids from 1016 stalled the Saxon efforts and very little from the Saxon abbey was incorporated in the later forms.

Norman abbey

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2022) |

Much of the current layout and proportions of the structure date from the first Norman abbot, Paul of Caen (1077–1093).[19] The 14th abbot, he was appointed by his uncle, the new Archbishop of Canterbury, Lanfranc.

Building work started in the year of Abbot Paul's arrival. The design and construction was overseen by the Norman Robert the Mason. The plan has very limited Anglo-Saxon elements and is clearly influenced by the French work at Cluny, Bernay and Caen, and shares a similar floor plan to Saint-Étienne in Caen and Lanfranc's Canterbury—although the poorer quality building material was a new challenge for Robert and he clearly borrowed some Roman techniques, which were learned while gathering material in the ruins of Verulamium.

To make maximum use of the hilltop the Abbey was oriented to the south-east. The cruciform abbey was the largest built in England at that time, it had a chancel of four bays, a transept containing seven apses, and a nave of ten bays—fifteen bays long overall. Robert gave particular attention to solid foundations, running a continuous wall of layered bricks, flints and mortar below and pushing the foundations down to twelve feet to hit bedrock. Below the crossing tower special large stones were used.

The tower was a particular triumph—it is the only 11th-century great crossing tower still standing in England. Robert began with special thick supporting walls and four massive brick piers. The four-level tower tapers at each stage with clasping buttresses on the three lower levels and circular buttresses on the fourth stage. The entire structure masses 5,000 tons and is 144 feet high. The tower was probably topped with a Norman pyramidal roof; the current roof is flat. The original ringing chamber had five bells—two paid for by the Abbot, two by a wealthy townsman, and one donated by the rector of Hoddesdon. None of these bells has survived.

There was a widespread belief that the Abbey had two additional, smaller towers at the west end. No remains have been found.

The monastic abbey was completed in 1089 but not consecrated until Holy Innocents' Day (28 December), 1115, by the Archbishop of Rouen. King Henry I attended as did many bishops and nobles.

A nunnery (Sopwell Priory) was founded nearby in 1140.

Internally the Abbey church was bare of sculpture, almost stark. The plaster walls were coloured and patterned in parts, with extensive tapestries adding colour. Sculptural decoration was added, mainly ornaments, as it became more fashionable in the 12th century—especially after the Gothic style arrived in England around 1170.

In the current structure the original Norman arches survive principally under the central tower and on the north side of the nave. The arches in the rest of the building are Gothic, following medieval rebuilding and extensions, and Victorian era restoration.

The Abbey was extended in the 1190s by Abbot John de Cella (also known as John of Wallingford) (1195–1214); as the number of monks grew from fifty to over a hundred, the Abbey church was extended westwards with three bays added to the nave. The severe Norman west front was also rebuilt by Hugh de Goldclif—although how is uncertain; it was very costly but its 'rapid' weathering and later alterations have erased all but fragments. A more prominent shrine and altar to Saint Amphibalus were also added.[13] The work was very slow under de Cella and was not completed until the time of Abbot William de Trumpington (1214–1235). The low Norman tower roof was demolished and a new, much higher, broached spire was raised, sheathed in lead.

The St Albans Psalter (c. 1130–1145) is the best known of a number of important Romanesque illuminated manuscripts produced in the Abbey scriptorium. Later, Matthew Paris, a monk at St Albans from 1217 until his death in 1259, was important both as a chronicler and an artist. Eighteen of his manuscripts survive and are a rich source of contemporary information for historians.

Nicholas Breakspear was born near St Albans, reportedly at Abbots Langley, and applied to be admitted to the Abbey as a novice, but he was turned down. He eventually managed to be accepted into an abbey in France. In 1154 he was elected Pope Adrian IV, the only English Pope there has ever been.[20][21] The head of the Abbey was confirmed as the premier abbot in England also in 1154.

-

Psalm 22:1-8 in the St. Albans Psalter. The first words of the Psalm in the Latin Vulgate are "Deus, Deus meus," abbreviated here as DS DS MS.

-

Psalm 137 Initial S

-

Initial at the start of the "Our Father"

-

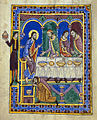

Christ in the house of Simon the Pharisee, with Mary Magdalene washing his feet, Luke 7:36–50

-

Jesus's Agony in the Garden

-

Mary Magdalene announces the Risen Christ

The Abbey had a number of daughter houses, ranging from Tynemouth Priory[22] in the north to Binham Priory near the Norfolk coast.[23]

13th to 15th centuries

[edit]

An earthquake shook the Abbey in 1250 and damaged the eastern end of the church. In 1257 the dangerously cracked sections were knocked down — three apses and two bays. The thick Presbytery wall supporting the tower was left. The rebuilding and updating was completed during the rule of Abbot Roger de Norton (1263–90) who founded an additional market in Watford.[24]

On 10 October 1323 two piers on the south side of the nave collapsed dragging down much of the roof and wrecking five bays. Mason Henry Wy undertook the rebuilding, matching the Early English style of the rest of the bays but adding distinctly 14th-century detailing and ornaments. The shrine to St Amphibalus had also been damaged and it was remade.

Richard of Wallingford, abbot from 1297 to 1336 and a mathematician and astronomer, designed a celebrated astronomical clock, which was completed by William of Walsham after his death, but apparently destroyed during the Reformation. In 1334 he founded two additional markets in Codicote and High Barnet.[24]

A new gateway, now called the Abbey Gateway, was built to the Abbey grounds in 1365, which was the only part of the monastery buildings (besides the church) to survive the dissolution, later being used as a prison and now (since 1871) part of St Albans School. The other monastic buildings were located to the south of the gateway and church.

In the 15th century a large west window of nine main lights and a deep traced head was commissioned by John of Wheathampstead. The spire was reduced to a 'Hertfordshire spike', the roof pitch greatly reduced and battlements liberally added. Further new windows, at £50 each, were put in the transepts by Abbot Wallingford (also known as William of Wallingford), who also had a new high altar screen made.

Dissolution and after

[edit]After the death of Abbot Ramryge in 1521 the Abbey fell into debt and slow decay under three weak abbots. At the time of the Dissolution of the Monasteries and its surrender on 5 December 1539 the income was £2,100 annually. The abbot and remaining forty monks were pensioned off and then the buildings were looted. All gold, silver and gilt objects were carted away with all other valuables; stonework was broken and defaced and graves opened to search for riches. The Abbey became part of the diocese of Lincoln in 1542 and was moved to the diocese of London in 1550. [citation needed]

The buildings suffered—neglect, second-rate repairs, even active damage. Richard Lee purchased all the buildings, except the church and chapel and some other Crown premises, in 1538,[25] 1539,[26] or 1540.[27] In 1549, Lee began systematic demolition, including the removal and sale of the stone, except for what may have been retained to improve Lee Hall at Sopwell.[25][26][28] In March 1550, Lee returned the land to the abbot by grant.[29] The area was named Abbey Ruins for the next 200 years or so.[citation needed]

In 1553 the Lady chapel was used as a school, the Great Gatehouse as a town jail, some other buildings passed to the Crown, and the Abbey Church was sold to the town for £400 in 1553 by King Edward VI to be the church of the parish.

The cost of upkeep fell upon the town, although in 1596 and at irregular intervals later the Archdeacon was allowed to collect money for repairs by Brief in the diocese. After James I visited in 1612 he authorised another Brief, which collected around £2,000—most of which went on roof repairs. The English Civil War slashed the monies spent on repairs, while the Abbey Church was used to hold prisoners of war and suffered from their vandalism, as well as that of their guards. Most of the metal objects that had survived the Dissolution were also removed and other ornamental parts were damaged in Puritan sternness. Another round of fund-raising in 1681–1684 was again spent on the roof, repairing the Presbytery vault. A royal grant from William III and Mary II in 1689 went on general maintenance, 'repairs' to conceal some of the then considered unfashionable Gothic features, and on new internal fittings. There was a second royal grant from William in 1698.

By the end of the 17th century the dilapidation was sufficient for a number of writers to comment upon it.

In 1703, from 26 November to 1 December, the Great Storm raged across southern England; the Abbey lost the south transept window which was replaced in wood at a cost of £40. The window was clear glass with five lights and three transoms in an early Gothic Revival style by John Hawgood. Other windows, although not damaged in the storm, were a constant drain on the Abbey budget in the 18th century.

A brief written in 1723–1724, seeking £5,775, notes a great crack in the south wall, that the north wall was eighteen inches from vertical, and that the roof timbers were decayed to the point of danger. The money raised was spent on the nave roof over ten bays.

Another brief was not issued until 1764. Again the roof was rotting, as was the south transept window, walls were cracked or shattered in part and the south wall had subsided and now leant outwards. Despite a target of £2,500 a mere £600 was raised.

In the 1770s the Abbey came close to demolition; the expense of repairs meant a scheme to destroy the Abbey and erect a smaller church almost succeeded.

A storm in 1797 caused some subsidence, cracking open graves, scattering pavement tiles, flooding the church interior and leaving a few more arches off-vertical.

19th century

[edit]

This century was marked with a number of repair schemes. The Abbey received some money from the 1818 "Million Act", and in 1820, £450 was raised to buy an organ—a second-hand example made in 1670.

The major efforts to revive the Abbey Church came under four men—L. N. Cottingham, H. J. B. Nicholson (Rector), and, especially, George Gilbert Scott and Edmund Beckett, 1st Baron Grimthorpe.

In February 1832 a portion of the clerestory wall fell through the roof of the south aisle, leaving a hole almost thirty feet long. With the need for serious repair work evident, the architect Lewis Nockalls Cottingham was called in to survey the building. His Survey was presented in 1832 and was worrying reading: everywhere mortar was in a wretched condition and wooden beams were rotting and twisting. Cottingham recommended new beams throughout the roof and a new steeper pitch, removal of the spire and new timbers in the tower, new paving, ironwork to hold the west transept wall up, a new stone south transept window, new buttresses, a new drainage system for the roof, new ironwork on almost all the windows, and on and on. He estimated a cost of £14,000. A public subscription of £4,000 was raised, of which £1,700 vanished in expenses. With the limited funds the clerestory wall was rebuilt, the nave roof re-leaded, the tower spike removed, some forty blocked windows reopened and glazed, and the south window remade in stone.

Henry Nicholson, rector from 1835 to 1866, was also active in repairing the Abbey Church—as far as he could, and in uncovering lost or neglected Gothic features.

In 1856 repair efforts began again; £4,000 was raised and slow moves started to gain the Abbey the status of cathedral. George Gilbert Scott was appointed the project architect and oversaw a number of works from 1860 until his death in 1878.

Scott began by having the medieval floor restored, necessitating the removal of tons of earth, and fixing the north aisle roof. From 1872 to 1877 the restored floors were re-tiled in matching stone and copies of old tile designs. A further 2,000 tons of earth were shifted in 1863 during work on the foundation and a new drainage system. In 1870 the tower piers were found to be badly weakened with many cracks and cavities. Huge timbers were inserted and the arches filled with brick as an emergency measure. Repair work took until May 1871 and cost over £2,000. The south wall of the nave was now far from straight; Scott reinforced the north wall and put in scaffolding to take the weight of the roof off the wall, then had it jacked straight in under three hours. The wall was then buttressed with five huge new masses and set right. Scott was lauded as "saviour of the Abbey." From 1870 to 1875 around £20,000 was spent on the Abbey.

In 1845 St Albans was transferred from the Diocese of Lincoln to the Diocese of Rochester. Then, in 1875, the Bishopric of St Albans Act was passed and on 30 April 1877 the See of St Albans was created, which comprises about 300 churches in the counties of Hertfordshire and Bedfordshire. Thomas Legh Claughton, then Bishop of Rochester, elected to take the northern division of his old diocese and on 12 June 1877 was enthroned first Bishop of St Albans, a position he held until 1890. He is buried in the churchyard on the north side of the nave.

George Gilbert Scott was working on the nave roof, vaulting and west bay when he died on 27 March 1878. His plans were partially completed by his son, John Oldrid Scott, but the remaining work fell into the hands of Edmund Beckett, 1st Baron Grimthorpe, whose efforts have attracted much controversy—Nikolaus Pevsner calling him a "pompous, righteous bully."[31] However, he donated much of the immense sum of £130,000 the work cost.

Whereas Scott's work had clearly been in sympathy with the existing building, Grimthorpe's plans reflected the Victorian ideal. Indeed, he spent considerable time dismissing and criticising the work of Scott and the efforts of his son.

Grimthorpe first reinstated the original pitch of the roof, although the battlements added for the lower roof were retained. Completed in 1879, the roof was leaded, following on Scott's desires.

His second major project was the most controversial. The west front, with the great Wheathampstead window, was cracked and leaning, and Grimthorpe, never more than an amateur architect, designed the new front himself—attacked as dense, misproportioned and unsympathetic: "His impoverishment as a designer ... [is] evident"; "this man, so practical and ingenious, was utterly devoid of taste ... his great qualities were marred by arrogance ... and a lack of historic sense".[citation needed] Counter proposals were deliberately substituted by Grimthorpe for poorly drawn versions and Grimthorpe's design was accepted. During building it was considerably reworked in order to fit the actual frontage and is not improved by the poor quality sculpture. Work began in 1880 and was completed in April 1883, having cost £20,000.

Grimthorpe was noted for his aversion to the Perpendicular—to the extent that he would have sections he disliked demolished as "too rotten" rather than remade. In his reconstruction, especially of windows, he commonly mixed architectural styles carelessly (see the south aisle, the south choir screen and vaulting). He spent £50,000 remaking the nave. Elsewhere he completely rebuilt the south wall cloisters, with new heavy buttresses, and removed the arcading of the east cloisters during rebuilding the south transept walls. In the south transept he completely remade the south face, completed in 1885, including the huge lancet window group—his proudest achievement—and the flanking turrets; a weighty new tiled roof was also made. In the north transept Grimthorpe had the Perpendicular window demolished and his design inserted—a rose window of circles, cusped circles and lozenges arrayed in five rings around the central light, sixty-four lights in total, each circle with a different glazing pattern.

Grimthorpe continued through the Presbytery in his own style, adapting the antechapel for Consistory Courts, and into the Lady Chapel. After a pointed lawsuit with Henry Hucks Gibbs, 1st Baron Aldenham, over who should direct the restoration, Grimthorpe had the vault remade and reproportioned in stone, made the floor in black and white marble (1893), and had new Victorian arcading and sculpture put below the canopy work. Externally the buttresses were expanded to support the new roof, and the walls were refaced.

As early as 1897, Grimthorpe was having to return to previously renovated sections to make repairs. His use of over-strong cement led to cracking, while his fondness for ironwork in windows led to corrosion and damage to the surrounding stone.

Grimthorpe died in 1905 and was interred in the churchyard. He left a bequest for continuing work on the buildings.

During this century the name St Albans Abbey was given to one of the town's two railway stations.

20th century

[edit]John Oldrid Scott (died 1913) (George Gilbert Scott's son), despite frequent clashes with Grimthorpe, had continued working within the cathedral. Scott was a steadfast supporter of the Gothic revival and designed the tomb of the first bishop; he had a new bishop's throne built (1903), together with commemorative stalls for Festing (a bishop) and two archdeacons, and new choir stalls. He also repositioned and rebuilt the organ (1907). Further work was interrupted by the war.

A number of memorials to the war were added to the cathedral, notably the painting The Passing of Eleanor by Frank Salisbury (stolen 1973) and the reglazing of the main west window, dedicated in 1925.

Following the Enabling Act of 1919, control of the buildings passed to a Parochial Church Council (replaced by the Cathedral Council in 1968), who appointed the woodwork specialist John Rogers as Architect and Surveyor of the Fabric. He uncovered extensive death watch beetle damage in the presbytery vault and oversaw the repair (1930–31). He had four tons of rubbish removed from the crossing tower and the main timbers reinforced (1931–32), and invested in the extensive use of insecticide throughout the wood structures. In 1934, the eight bells were overhauled and four new bells added to be used in the celebration of George V's silver jubilee.

Cecil Brown was architect and surveyor from 1939 to 1962. At first he merely oversaw the lowering of the bells for the war and established a fire watch, with the pump in the slype. After the war, in the 1950s, the organ was removed, rebuilt and reinstalled, and new pews added. His major work was on the crossing tower. Grimthorpe's cement was found to be damaging the Roman bricks: every brick in the tower was replaced as needed and reset in proper mortar by one man, Walter Barrett. The tower ceiling was renovated as were the nave murals. Brown established the Muniments Room to gather and hold all the church documents.

In 1972, to encourage a closer link between celebrant and congregation in the nave, the massive nine-tonne pulpit along with the choir stalls and permanent pews was dismantled and removed. The altar space was enlarged and improved. New 'lighter' wood (limed oak) choir stalls were put in, and chairs replaced the pews. A new wooden pulpit was acquired from a Norfolk church and installed in 1974. External floodlighting was added in 1975.

A major survey in 1974 revealed new leaks, decay and other deterioration, and a ten-year restoration plan was agreed. Again the roofing required much work. The nave and clerestory roofs were repaired in four stages with new leading. The nave project was completed in 1984 at a total cost of £1.75 million. The clerestory windows were repaired with the corroded iron replaced with delta bronze and other Grimthorpe work on the clerestory was replaced. Seventy-two new heads for the corbel table were made. Grimthorpe's west front was cracking, again due to the use originally of too strong a mortar, and was repaired.

A new visitors' centre was proposed in 1970. Planning permission was sought in 1973; there was a public inquiry and approval was granted in 1977. Constructed to the south side of the cathedral, close to the site of the original chapter house of the Abbey, the new 'Chapter House' cost around £1 million and was officially opened on 8 June 1982 by Queen Elizabeth II. The main building material was 500,000 replica Roman bricks.

Other late 20th-century works include the restoration of Alban's shrine, with a new embroidered canopy, and the stained glass designed by Alan Younger for Grimthorpe's north transept rose window,[32] unveiled in 1989 by Diana, Princess of Wales. In 2015 seven new painted stone statues by Rory Young were installed in the medieval niches in the nave screen. This was a rare occurrence, as the last painted figures placed in a church screen were put there before the Reformation and the English Civil War.[33]

21st century

[edit]The shrine of St Amphibalus was restored between 2019 and 2021, funded by a grant and the contribution of over a thousand donors. Due to be unveiled in 2020, work was delayed due to the Covid pandemic, and a new figure wearing a face mask was added to commemorate this.[11]

Modern times

[edit]The bishop of St Albans is Alan Smith, installed in September 2009. Jonathan Smith is Archdeacon of St Albans, installed in October 2008. On 4 December 2021, Jo Kelly-Moore became the tenth dean of the cathedral.[34]

Robert Runcie, later Archbishop of Canterbury, was Bishop of St Albans from 1970 to 1980 and returned to live in the city after his retirement; he is commemorated by a gargoyle on the cathedral as well as being buried in the graveyard. Colin Slee, former dean of Southwark Cathedral, was sub-dean at St Albans under Runcie and the then dean, Peter Moore. The bishop's residence, Abbey Gate House, is in Abbey Mill Lane, St Albans, as is the house of the bishop of Hertford. Eric James, Chaplain Extraordinary to the Queen, was canon at St Albans for many years.

Dean and chapter

[edit]

As of 18 November 23:[35]

- Dean – Jo Kelly-Moore (since 4 December 2021 installation)[34]

- Canon Chancellor – Kevin Walton (since 2008 installation)

- Diocesan Director of Ministry & Diocesan Canon – Tim Bull (since 2013)

- Diocesan Director of Mission & Diocesan Canon – Tim Lomax (since 2016)

- Canon for Mission and Pastoral Care – Will Gibbs (since 2022)

Minor Canons[35]

- Youth Chaplain – Calum Zuckert (since 2021)

- Precentor – Vanessa Jefferson (since 2023)

Music and choirs

[edit]Organ

[edit]- Details of the organ from the National Pipe Organ Register.

- Details of the restoration of the organ being undertaken 2007–09; article on the Cathedral's website dated August 2007 by Andrew Lucas, the Master of the Music.

- Details of the new specification following the major restoration by Harrison & Harrison completed in March 2009.

Organists

[edit]The master of the music and the assistant master of the music share the responsibility of directing the St Albans Cathedral Choir and the St Albans Cathedral Girls' Choir respectively.

The earliest known name of an organist at St Albans is Adam from the early 13th century. Robert Fayrfax, the prominent English Renaissance composer, is recorded as being organist from 1498 to 1502, and was buried there following his death some 20 years later. Since 1820 the post of organist and master of the music has been held by a number of well-known musicians, including Peter Hurford, Stephen Darlington and Barry Rose. The current master of the music, since 1998, is Andrew Lucas.[36] The assistant master of music at the cathedral is sometimes also the master of music at St Albans School — for example, Simon Lindley and Andrew Parnell.

Since 1963 the cathedral has been home to the St Albans International Organ Festival, founded by Peter Hurford, and winners of which include Dame Gillian Weir, Thomas Trotter and Naji Hakim.

Bells

[edit]In total, there are 23 bells housed in the tower. The main ring of 12 bells (with a sharp 2nd) was cast in 2010 by the Whitechapel Bell Foundry.[37] These replaced the previous ring, 8 of which still remain in the tower and are used for the clock chime and carillon; the carillon plays a different tune every day of the week.[38]

In the 17th century the cathedral housed a ring of 5 bells, until they were recast and augmented to 6 in 1699. In 1731 the bells were augmented to a ring of 8 by adding two new bells. Finally, in 2010 the 13 new bells were cast, and were rung for the first time at Easter 2011.[39] The oldest bell in the tower was cast in c.1290 and is still used today as the sanctus bell.

Burials

[edit]- Robert "of the Chamber" Breakspear (died 1110), priest of the diocese of Bath, then monk at St Albans; father of Nicholas who became the only English Pope, Pope Adrian IV.

- Richard d'Aubeney (1097–1119), Abbot

- Ralph Gubion (died 7 July 1150), Abbot and historian

- Robert of Gorron (died c. 1170), Abbot of St Albans

- Simon Warin (died 1195), Abbot

- John of Wallingford (died 1214), Abbot

- William of Trumpington, Abbot (1214–35)

- John of Hertford (died 1335), Abbot

- Adam Rous (died 1370), Surgeon to King Henry III

- Thomas de la Mare (died 1396), Abbot

- John de la Moote, Abbot (1396–1401)

- John Whethamstede (died 1465), Abbot

- Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester (died 1447), the fourth son of King Henry IV

- Casualties of the First Battle of St Albans:

- Thomas Clifford, 8th Baron de Clifford (1414–55)

- Henry Percy, 2nd Earl of Northumberland (1392/1393–1455)

- Edmund Beaufort, 1st Duke of Somerset (1406–55)

- Sir Anthony (or Antony) Grey (died 1480), brother-in-law of Elizabeth Woodville, queen consort of Edward IV

- Thomas Legh Claughton, first Bishop of St Albans 1877–90, buried in the churchyard

- Edmund Beckett, 1st Baron Grimthorpe (1816–1905)

- Robert Runcie, Bishop of St Albans 1970–80, Archbishop of Canterbury 1980–91, buried in the churchyard and commemorated with a gargoyle on the roof

See also

[edit]- Architecture of the medieval cathedrals of England

- English Gothic architecture

- History of St Albans

- List of cathedrals in the United Kingdom

- List of Gothic cathedrals in Europe

Notes

[edit]- ^ Historic England. "ABBEY CHURCH OF ST ALBAN (1103163)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- ^ a b "Highlights - The Cathedral and Abbey Church of Saint Alban". www.stalbanscathedral.org. November 2018. Archived from the original on 8 March 2019. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- ^ "St Albans abbey — History | A History of the County of Hertford: volume 2 (pp. 483–488)". British-history.ac.uk. 22 June 2003. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ^ "a Short History of the Abbey / Perkins, Thomas, 1842–1907". Infomotions.com. 8 October 2006. Archived from the original on 28 May 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ^ "Home - The Cathedral and Abbey Church of Saint Alban". www.stalbanscathedral.org. Archived from the original on 6 March 2011. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ^ Perkins, Thomas (8 October 2006). Bell's Cathedrals: The Cathedral Church of Saint AlbansWith an Account of the Fabric & a Short History of the Abbey. Archived from the original on 1 March 2019. Retrieved 28 February 2019 – via Project Gutenberg.

- ^ a b c d Bede. "Ecclesiastical History of the English People". Internet History Sourcebook. Fordham University. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ^ a b "Medieval St Albans". Archived from the original on 18 September 2013. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ^ "Holywell Hill". salbani.co.uk. Archived from the original on 18 September 2013. Retrieved 18 November 2009.

- ^ Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, Project Gutenberg, archived from the original on 12 June 2018, retrieved 10 June 2018

- ^ a b "Covid: St Albans cathedral's new carving features facemask". BBC News. 7 May 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ "Story of St Alban – The Cathedral and Abbey Church of Saint Alban". www.stalbanscathedral.org. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- ^ a b "The Medieval Abbey – The Cathedral and Abbey Church of Saint Alban". www.stalbanscathedral.org. Archived from the original on 25 September 2018. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- ^ Rushbrook Williams, L. F. (1917). History of the Abbey of St Alban (1st ed.). London: Longmans, Green and Co.

- ^ Nicholson, Henry (1870). The Abbey of Saint Alban, some extracts from its early history and a dedication of its conventional church. London: Bell and Daldy.

- ^ Corbett, James (1997). A History of St Albans (1st ed.). Chichester: Philmore & Co. Ltd. pp. 14, 67, 116, 126. ISBN 1-86077-048-7.

- ^ "St Albans Cathedral, a former Benedictine Abbey Church, its history and attractions". www.easterncathedrals.org.uk.

- ^ St Albans Cathedral, Jarrold Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7117-1514-1, p. 9

- ^ "St Albans abbey: History - British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 1 March 2019. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- ^ "Famous people in Three Rivers - a Ragamuffin from Bedmond". Three Rivers Museum Trust. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ Sheldon, Liberty (30 April 2022). "England's first and only Pope and his life in Abbots Langley". HertsLive. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ "Priors, Kings and Soldiers - North Tyneside Council". Northtyneside.gov.uk. 1 July 1999. Archived from the original on 6 January 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ Mee, Arthur Mee. Norfolk, Hodder and Stoughton,1972, p. 32, ISBN 0-340-15061-0

- ^ a b Letters, Samantha (23 February 2005). "Hertfordshire". Gazetteer Of Markets and Fairs In England And Wales To 1516. Archived from the original on 25 August 2022. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ a b "Sopwell ruins". St Albans & Hertfordshire Architectural and Archaeological Society. 20 May 2021. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ a b Milligan, Mark (28 October 2021). "Ten historic sites in Hertfordshire". HeritageDaily - Archaeology News. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ "Sopwell Ruins". St Albans Museums. 15 August 2022. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ CgMs Consulting (May 2007). "2.2.1". Former Grill Bar (The Mile House) London Road, St Albans, Hertfordshire: Archaeological Evaluation Report (PDF) (Report) (65130.03 ed.). Salisbury, England: Wessex Archaeology. Retrieved 8 February 2024.

The Site is situated on land once owned by Richard Lee, one of the main property owners in mid-sixteenth century St Albans... he became bailiff and farmer of the medieval Priory of Sopwell, and in 1549 began alterations, calling his new house 'Lee Hall'.

- ^ "St. Albans". History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ The Cathedral Church of Saint Albans, Thomas Perkins, 205, p.21

- ^ Pevsner, Nikolaus (1951). The Buildings of England: Yorkshire: The West Riding. Penguin Books.

- ^ Alan Younger Archived 1 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine: Obituary in The Daily Telegraph, 2004-06-08

- ^ "Cirencester sculptor Rory Young completes five-year art project at St Albans Cathedral". 25 May 2015. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- ^ a b "Jo Kelly-Moore installed as Dean of St Albans". St Albans Cathedral. 4 December 2021. Archived from the original on 13 December 2021.

- ^ a b "Ministry Team". St Albans Cathedral. 18 November 2023.

- ^ "Andrew Lucas (St Albans Bach Choir)". Archived from the original on 14 January 2010.

- ^ "The Bells - The Cathedral and Abbey Church of Saint Alban". www.stalbanscathedral.org. Archived from the original on 14 June 2018. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- ^ "List of Hymns Played by the Carillon" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- ^ "Cathedral Bells - The Cathedral and Abbey Church of Saint Alban". www.stalbanscathedral.org. Archived from the original on 14 June 2018. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

References

[edit]- Roberts, Eileen (1993). The Hill of the Martyr: an Architectural History of St Albans Abbey. Book Castle. ISBN 1-871199-26-3.

Further reading

[edit]- Lane Fox, Robin (1986). Pagans and Christians in the Mediterranean World from the Second Century AD to the Conversion of Constantine. London, UK: Penguin Books. p. 273. ISBN 978-0-14-102295-6.

External links

[edit]- Monasteries in Hertfordshire

- Anglo-Saxon monastic houses

- 11th-century church buildings in England

- 1539 disestablishments in England

- Anglican cathedrals in England

- Buildings and structures in St Albans

- History of St Albans

- Church of England church buildings in Hertfordshire

- Grade I listed churches in Hertfordshire

- Grade I listed cathedrals

- English churches with Norman architecture

- English Gothic architecture in Hertfordshire

- 8th-century establishments in England

- Diocese of St Albans

- Scheduled monuments in Hertfordshire

- Churches in Hertfordshire

- Monasteries dissolved under the English Reformation

- Burial sites of the Beaufort family

- Basilicas (Church of England)

- 793 establishments

- Churches completed in the 790s

- English churches dedicated to St Alban