Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton | |

|---|---|

Hamilton portrait by John Trumbull, 1792 | |

| 1st United States Secretary of the Treasury | |

| In office September 11, 1789 – January 31, 1795 | |

| President | George Washington |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Oliver Wolcott Jr. |

| 8th Senior Officer of the United States Army | |

| In office December 14, 1799 – June 15, 1800 | |

| President | John Adams |

| Preceded by | George Washington |

| Succeeded by | James Wilkinson |

| Delegate to the Congress of the Confederation from New York | |

| In office November 3, 1788 – March 2, 1789 | |

| Preceded by | Egbert Benson |

| Succeeded by | Seat abolished |

| In office November 4, 1782 – June 21, 1783 | |

| Preceded by | Seat established |

| Succeeded by | Seat abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 11, 1755 or 1757[a] Charlestown, Colony of Nevis, British Leeward Islands |

| Died | (aged 47 or 49) New York City, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Gunshot wound |

| Resting place | Trinity Church Cemetery |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Federalist |

| Spouse | |

| Children | |

| Relatives | Hamilton family |

| Education | King's College Columbia College (MA) |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service |

|

| Rank | Major general |

| Commands | U.S. Army Senior Officer |

| Battles/wars | |

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757[a] – July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first U.S. secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795 during George Washington's presidency.

Born out of wedlock in Charlestown, Nevis, Hamilton was orphaned as a child and taken in by a prosperous merchant. He pursued his education in New York City where, despite his young age, he was a prolific and widely read pamphleteer advocating for the American revolutionary cause, though an anonymous one. He then served as an artillery officer in the American Revolutionary War, where he saw military action against the British in the New York and New Jersey campaign, served for years as an aide to General George Washington, and helped secure American victory at the climactic Siege of Yorktown. After the Revolutionary War, Hamilton served as a delegate from New York to the Congress of the Confederation in Philadelphia. He resigned to practice law and founded the Bank of New York. In 1786, Hamilton led the Annapolis Convention to replace the Articles of Confederation with the Constitution of the United States, which he helped ratify by writing 51 of the 85 installments of The Federalist Papers.

As a trusted member of President Washington's first cabinet, Hamilton served as the first U.S. Secretary of the Treasury. He envisioned a central government led by an energetic president, a strong national defense, and an industrial economy. He successfully argued that the implied powers of the Constitution provided the legal authority to fund the national debt, assume the states' debts, and create the First Bank of the United States, which was funded by a tariff on imports and a whiskey tax. He opposed American entanglement with the succession of unstable French Revolutionary governments and advocated in support of the Jay Treaty under which the U.S. resumed friendly trade relations with the British Empire. He also persuaded Congress to establish the Revenue Cutter Service. Hamilton's views became the basis for the Federalist Party, which was opposed by the Democratic-Republican Party led by Thomas Jefferson. Hamilton and other Federalists supported the Haitian Revolution, and Hamilton helped draft the constitution of Haiti.

After resigning as Secretary of the Treasury, Hamilton resumed his legal and business activities. He was a leader in the abolition of the international slave trade. In the Quasi-War, Hamilton called for mobilization against France, and President John Adams appointed him major general. The army, however, did not see combat. Outraged by Adams' response to the crisis, Hamilton opposed his reelection campaign. Jefferson and Aaron Burr tied for the presidency in the electoral college and, despite philosophical differences, Hamilton endorsed Jefferson over Burr, whom he found unprincipled. When Burr ran for governor of New York in 1804, Hamilton again campaigned against him, arguing that he was unworthy. Taking offense, Burr challenged Hamilton to a duel. In the July 11, 1804, duel in Weehawken, New Jersey, Burr shot Hamilton in the stomach. Hamilton was immediately transported to the home of William Bayard Jr. in Greenwich Village for medical attention, but succumbed to his wounds the following day.

Scholars generally regard Hamilton as an astute and intellectually brilliant administrator, politician, and financier who was sometimes impetuous. His ideas are credited with laying the foundation for American government and finance.

Early life and education

Hamilton was born and spent the early part of his childhood in Charlestown, the capital of Nevis in the British Leeward Islands. Hamilton and his older brother, James Jr.,[5] were born out of wedlock to Rachel Lavien (née Faucette),[b] a married woman of half-British and half-French Huguenot descent,[c][14] and James A. Hamilton, a Scotsman who was the fourth son of Alexander Hamilton, the laird of Grange, Ayrshire.[15]

Rachel Lavien was married on Saint Croix.[16] In 1750, Lavien left her husband and first son before travelling to Saint Kitts, where she met James Hamilton.[16] Hamilton and Lavien moved together to Nevis, her birthplace, where she had inherited a seaside lot in town from her father.[1] While their mother was living, Alexander and James Jr. received individual tutoring[1] and classes in a private school led by a Jewish headmistress.[17] Alexander supplemented his education with a family library of 34 books.[18]

James Hamilton later abandoned Rachel Lavien and their two sons, allegedly to "spar[e] [her] a charge of bigamy...after finding out that her first husband intend[ed] to divorce her under Danish law on grounds of adultery and desertion."[15] Lavien then moved with her two children to Saint Croix, where she supported them by managing a small store in Christiansted. Lavien contracted yellow fever and died on February 19, 1768, leaving Hamilton orphaned.[19] Lavien's death may have had a severe emotional impact on Hamilton.[20] In probate court, Lavien's "first husband seized her estate"[15] and obtained the few valuables that she had owned, including some household silver. Many items were auctioned off, but a friend purchased the family's books and returned them to Hamilton.[21]

The brothers were briefly taken in by their cousin Peter Lytton. However, Lytton took his own life in July 1769, leaving his property to his mistress and their son, and the Hamilton brothers were subsequently separated.[21] James Jr. apprenticed with a local carpenter, while Alexander was given a home by Thomas Stevens, a merchant from Nevis.[22]

Hamilton became a clerk at Beekman and Cruger, a local import-export firm that traded with the Province of New York and New England.[23] Despite being only a teenager, Hamilton proved capable enough as a trader to be left in charge of the firm for five months in 1771 while the owner was at sea.[24] He remained an avid reader, and later developed an interest in writing and a life outside Saint Croix. He wrote a detailed letter to his father regarding a hurricane that devastated Christiansted on August 30, 1772.[25] The Presbyterian Reverend Hugh Knox, a tutor and mentor to Hamilton, submitted the letter for publication in the Royal Danish-American Gazette. Biographer Ron Chernow found the letter astounding because "for all its bombastic excesses, it does seem wondrous [that a] self-educated clerk could write with such verve and gusto" and that a teenage boy produced an apocalyptic "fire-and-brimstone sermon" viewing the hurricane as a "divine rebuke to human vanity and pomposity."[26] The essay impressed community leaders, who collected a fund to send Hamilton to the North American colonies for his education.[27]

In October 1772, Hamilton arrived by ship in Boston and proceeded from there to New York City, where he took lodgings with the Irish-born Hercules Mulligan, brother of a trader known to Hamilton's benefactors, who assisted Hamilton in selling cargo that was used to pay for his education and support.[28][29] Later that year, in preparation for college, Hamilton began to fill gaps in his education at the Elizabethtown Academy, a preparatory school run by Francis Barber in Elizabeth, New Jersey. While there, he came under the influence of William Livingston, a local leading intellectual and revolutionary with whom he lived for a time.[30][31][32]

Hamilton entered Mulligan's alma mater King's College, now Columbia University, in New York City, in the autumn of 1773 as a private student, while again boarding with Mulligan until officially matriculating in May 1774.[33] His college roommate and lifelong friend Robert Troup spoke glowingly of Hamilton's clarity in concisely explaining the patriots' case against the British in what is credited as Hamilton's first public appearance on July 6, 1773.[34] As King's College students, Hamilton, Troup, and four other undergraduates formed an unnamed literary society that is regarded as a precursor of the Philolexian Society.[35][36]

In 1774, Church of England clergyman Samuel Seabury published a series of pamphlets promoting the Loyalist cause and Hamilton responded anonymously to it, with his first published political writings, A Full Vindication of the Measures of Congress and The Farmer Refuted. Seabury essentially tried to provoke fear in the colonies with an objective of preventing the colonies from uniting against the British.[37] Hamilton published two additional pieces attacking the Quebec Act,[38] and may have also authored the 15 anonymous installments of "The Monitor" for Holt's New York Journal.[39] Hamilton was a supporter of the Revolutionary cause before the war began, although he did not approve of mob reprisals against Loyalists. On May 10, 1775, Hamilton won credit for saving his college's president, Loyalist Myles Cooper, from an angry mob by speaking to the crowd long enough to allow Cooper to escape.[40] Hamilton was forced to discontinue his studies before graduating when the college closed its doors during the British occupation of New York City.[41]

Revolutionary War (1775–1782)

Early military career

In 1775, after the first engagement of American patriot troops with the British at Lexington and Concord, Hamilton and other King's College students joined a New York volunteer militia company called the Corsicans, whose name reflected the Corsican Republic that was suppressed six years earlier and young American patriots regarded as a model to be emulated.[42]

Hamilton drilled with the company before classes in the graveyard of nearby St. Paul's Chapel. He studied military history and tactics on his own and was soon recommended for promotion.[43] Under fire from HMS Asia, and with support from Hercules Mulligan and the Sons of Liberty, he led his newly renamed unit the "Hearts of Oak" on a successful raid for British cannons in the Battery. The seizure of the cannons resulted in the unit being re-designated an artillery company.[44]: 13

Through his connections with influential New York patriots, including Alexander McDougall and John Jay, Hamilton raised the New York Provincial Company of Artillery of 60 men in 1776, and was elected captain.[45] The company took part in the campaign of 1776 in and around New York City; as rearguard of the Continental Army's retreat up Manhattan, serving at the Battle of Harlem Heights shortly after, and at the Battle of White Plains a month later. At the Battle of Trenton, the company was stationed at the high point of Trenton at the intersection of present-day Warren and Broad streets to keep the Hessians pinned in their Trenton barracks.[46][47]

Hamilton participated in the Battle of Princeton on January 3, 1777. After an initial setback, Washington rallied the Continental Army troops and led them in a successful charge against the British forces. After making a brief stand, the British fell back, some leaving Princeton, and others taking up refuge in Nassau Hall. Hamilton transported three cannons to the hall, and had them fire upon the building as others rushed the front door and broke it down. The British subsequently put a white flag outside one of the windows;[47] 194 British soldiers walked out of the building and laid down their arms, ending the battle in an American victory.[48]

While being stationed in Morristown, New Jersey, from December 1779 to March 1780, Hamilton met Elizabeth Schuyler, a daughter of General Philip Schuyler and Catherine Van Rensselaer. They married on December 14, 1780, at the Schuyler Mansion in Albany, New York.[49] They had eight children, Philip,[50] Angelica, Alexander, James,[51] John, William, Eliza, and another Philip.[52]

George Washington's staff

Hamilton was invited to become an aide to Continental Army general William Alexander, Lord Stirling, and another general, perhaps Nathanael Greene or Alexander McDougall.[53] He declined these invitations, believing his best chance for improving his station in life was glory on the Revolutionary War's battlefields. Hamilton eventually received an invitation he felt he could not refuse: to serve as Washington's aide with the rank of lieutenant colonel.[54] Washington believed that "Aides de camp are persons in whom entire confidence must be placed and it requires men of abilities to execute the duties with propriety and dispatch."[55]

Hamilton served four years as Washington's chief staff aide. He handled letters to the Continental Congress, state governors, and the most powerful generals of the Continental Army. He drafted many of Washington's orders and letters under Washington's direction, and he eventually issued orders on Washington's behalf over his own signature.[56] Hamilton was involved in a wide variety of high-level duties, including intelligence, diplomacy, and negotiation with senior army officers as Washington's emissary.[57][58]

During the Revolutionary War, Hamilton became the close friend of several fellow officers. His letters to the Marquis de Lafayette[59] and to John Laurens, employing the sentimental literary conventions of the late 18th century and alluding to Greek history and mythology,[60] have been read by Jonathan Ned Katz as revelatory of a homosocial or even homosexual relationship.[61] Biographer Gregory D. Massey amongst others, by contrast, dismisses all such speculation as unsubstantiated, describing their friendship as purely platonic camaraderie instead and placing their correspondence in the context of the flowery diction of the time.[62]

Field command

While on Washington's staff, Hamilton long sought command and a return to active combat. As the war drew nearer to an end, he knew that opportunities for military glory were diminishing. On February 15, 1781, Hamilton was reprimanded by Washington after a minor misunderstanding. Although Washington quickly tried to mend their relationship, Hamilton insisted on leaving his staff.[63] He officially left in March, and settled with his new wife Elizabeth Schuyler close to Washington's headquarters. He continued to repeatedly ask Washington and others for a field command. Washington continued to demur, citing the need to appoint men of higher rank. This continued until early July 1781, when Hamilton submitted a letter to Washington with his commission enclosed, "thus tacitly threatening to resign if he didn't get his desired command."[64]

On July 31, Washington relented and assigned Hamilton as commander of a battalion of light infantry companies of the 1st and 2nd New York Regiments and two provisional companies from Connecticut.[65] In the planning for the assault on Yorktown, Hamilton was given command of three battalions, which were to fight in conjunction with the allied French troops in taking Redoubts No. 9 and No. 10 of the British fortifications at Yorktown. Hamilton and his battalions took Redoubt No. 10 with bayonets in a nighttime action, as planned. The French also suffered heavy casualties and took Redoubt No. 9. These actions forced the British surrender of an entire army at Yorktown, marking the de facto end of the war, although small battles continued for two more years until the signing of the Treaty of Paris and the departure of the last British troops.[66][67]

Return to civilian life (1782–1789)

Congress of the Confederation

After Yorktown, Hamilton returned to New York City and resigned his commission in March 1782. He passed the bar in July after six months of self-directed education and, in October, was licensed to argue cases before the Supreme Court of New York.[68] He also accepted an offer from Robert Morris to become receiver of continental taxes for the New York state.[69] Hamilton was appointed in July 1782 to the Congress of the Confederation as a New York representative for the term beginning in November 1782.[70] Before his appointment to Congress in 1782, Hamilton was already sharing his criticisms of Congress. He expressed these criticisms in his letter to James Duane dated September 3, 1780: "The fundamental defect is a want of power in Congress ... the confederation itself is defective and requires to be altered; it is neither fit for war, nor peace."[71]

While on Washington's staff, Hamilton had become frustrated with the decentralized nature of the wartime Continental Congress, particularly its dependence upon the states for voluntary financial support that was not often forthcoming. Under the Articles of Confederation, Congress had no power to collect taxes or to demand money from the states. This lack of a stable source of funding had made it difficult for the Continental Army both to obtain its necessary provisions and to pay its soldiers. During the war, and for some time after, Congress obtained what funds it could from subsidies from the King of France, European loans, and aid requested from the several states, which were often unable or unwilling to contribute.[72]

An amendment to the Articles had been proposed by Thomas Burke, in February 1781, to give Congress the power to collect a five percent impost, or duty on all imports, but this required ratification by all states; securing its passage as law proved impossible after it was rejected by Rhode Island in November 1782. James Madison joined Hamilton in influencing Congress to send a delegation to persuade Rhode Island to change its mind. Their report recommending the delegation argued the national government needed not just some level of financial autonomy, but also the ability to make laws that superseded those of the individual states. Hamilton transmitted a letter arguing that Congress already had the power to tax, since it had the power to fix the sums due from the several states; but Virginia's rescission of its own ratification of this amendment ended the Rhode Island negotiations.[73][74]

Congress and the army

While Hamilton was in Congress, discontented soldiers began to pose a danger to the young United States. Most of the army was then posted at Newburgh, New York. Those in the army were funding much of their own supplies, and they had not been paid in eight months. Furthermore, after Valley Forge, the Continental officers had been promised in May 1778 a pension of half their pay when they were discharged.[75] By the early 1780s, due to the structure of the government under the Articles of Confederation, it had no power to tax to either raise revenue or pay its soldiers.[76] In 1782, after several months without pay, a group of officers organized to send a delegation to lobby Congress, led by Captain Alexander McDougall. The officers had three demands: the army's pay, their own pensions, and commutation of those pensions into a lump-sum payment if Congress were unable to afford the half-salary pensions for life. Congress rejected the proposal.[76]

Several congressmen, including Hamilton, Robert Morris, and Gouverneur Morris, attempted to use the so-called Newburgh Conspiracy as leverage to secure support from the states and in Congress for funding of the national government. They encouraged MacDougall to continue his aggressive approach, implying unknown consequences if their demands were not met, and defeated proposals designed to end the crisis without establishing general taxation: that the states assume the debt to the army, or that an impost be established dedicated to the sole purpose of paying that debt.[77]

Hamilton suggested using the Army's claims to prevail upon the states for the proposed national funding system.[78] The Morrises and Hamilton contacted General Henry Knox to suggest he and the officers defy civil authority, at least by not disbanding if the army were not satisfied. Hamilton wrote Washington to suggest that Hamilton covertly "take direction" of the officers' efforts to secure redress, to secure continental funding but keep the army within the limits of moderation.[79][80] Washington wrote Hamilton back, declining to introduce the army.[81] After the crisis had ended, Washington warned of the dangers of using the army as leverage to gain support for the national funding plan.[79][82]

On March 15, Washington defused the Newburgh situation by addressing the officers personally.[77] Congress ordered the Army officially disbanded in April 1783. In the same month, Congress passed a new measure for a 25-year impost—which Hamilton voted against[83]—that again required the consent of all the states; it also approved a commutation of the officers' pensions to five years of full pay. Rhode Island again opposed these provisions, and Hamilton's robust assertions of national prerogatives in his previous letter were widely held to be excessive.[84]

In June 1783, a different group of disgruntled soldiers from Lancaster, Pennsylvania, sent Congress a petition demanding their back pay. When they began to march toward Philadelphia, Congress charged Hamilton and two others with intercepting the mob.[79] Hamilton requested militia from Pennsylvania's Supreme Executive Council, but was turned down. Hamilton instructed Assistant Secretary of War William Jackson to intercept the men. Jackson was unsuccessful. The mob arrived in Philadelphia, and the soldiers proceeded to harangue Congress for their pay. Hamilton argued that Congress ought to adjourn to Princeton, New Jersey. Congress agreed, and relocated there.[85] Frustrated with the weakness of the central government, Hamilton while in Princeton, drafted a call to revise the Articles of Confederation. This resolution contained many features of the future Constitution of the United States, including a strong federal government with the ability to collect taxes and raise an army. It also included the separation of powers into the legislative, executive, and judicial branches.[85]

Return to New York

Hamilton resigned from Congress in 1783.[86] When the British left New York in 1783, he practiced there in partnership with Richard Harison. He specialized in defending Tories and British subjects, as in Rutgers v. Waddington, in which he defeated a claim for damages done to a brewery by the Englishmen who held it during the military occupation of New York. He pleaded for the mayor's court to interpret state law consistent with the 1783 Treaty of Paris, which had ended the Revolutionary War.[87][44]: 64–69

In 1784, Hamilton founded the Bank of New York.[88]

Long dissatisfied with the Articles of Confederation as too weak to be effective, Hamilton played a major leadership role at the 1786 Annapolis Convention. He drafted its resolution for a constitutional convention, and in doing so brought one step closer to reality his longtime desire to have a more effectual, more financially self-sufficient federal government.[89]

As a member of the legislature of New York, Hamilton argued forcefully and at length in favor of a bill to recognize the sovereignty of the State of Vermont, against numerous objections to its constitutionality and policy. Consideration of the bill was deferred to a later date. From 1787 to 1789, Hamilton exchanged letters with Nathaniel Chipman, a lawyer representing Vermont. After the Constitution of the United States went into effect, Hamilton said, "One of the first subjects of deliberation with the new Congress will be the independence of Kentucky, for which the southern states will be anxious. The northern will be glad to send a counterpoise in Vermont."[90] Vermont was admitted to the Union in 1791.[91]

In 1788, he was awarded a Master of Arts degree from his alma mater, the former King's College, now reconstituted as Columbia College.[92] It was during this post-war period that Hamilton served on the college's board of trustees, playing a part in the reopening of the college and placing it on firm financial footing.[93]

Constitution and The Federalist Papers

In 1787, Hamilton served as assemblyman from New York County in the New York State Legislature and was chosen as a delegate at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia by his father-in-law Philip Schuyler.[94]: 191 [95] Even though Hamilton had been a leader in calling for a new Constitutional Convention, his direct influence at the Convention itself was quite limited. Governor George Clinton's faction in the New York legislature had chosen New York's other two delegates, John Lansing Jr. and Robert Yates, and both of them opposed Hamilton's goal of a strong national government.[96][97] Thus, whenever the other two members of the New York delegation were present, they decided New York's vote, to ensure that there were no major alterations to the Articles of Confederation.[94]: 195

Early in the convention, Hamilton made a speech proposing a president-for-life; it had no effect upon the deliberations of the convention. He proposed to have an elected president and elected senators who would serve for life, contingent upon "good behavior" and subject to removal for corruption or abuse; this idea contributed later to the hostile view of Hamilton as a monarchist sympathizer, held by James Madison.[98] According to Madison's notes, Hamilton said in regards to the executive, "The English model was the only good one on this subject. The hereditary interest of the king was so interwoven with that of the nation, and his personal emoluments so great, that he was placed above the danger of being corrupted from abroad... Let one executive be appointed for life who dares execute his powers."[99]

Hamilton argued, "And let me observe that an executive is less dangerous to the liberties of the people when in office during life than for seven years. It may be said this constitutes as an elective monarchy ... But by making the executive subject to impeachment, the term 'monarchy' cannot apply ..."[99] In his notes of the convention, Madison interpreted Hamilton's proposal as claiming power for the "rich and well born". Madison's perspective all but isolated Hamilton from his fellow delegates and others who felt they did not reflect the ideas of revolution and liberty.[100]

During the convention, Hamilton constructed a draft for the Constitution based on the convention debates, but he never presented it. This draft had most of the features of the actual Constitution. In this draft, the Senate was to be elected in proportion to the population, being two-fifths the size of the House, and the president and senators were to be elected through complex multistage elections, in which chosen electors would elect smaller bodies of electors; they would hold office for life, but were removable for misconduct. The president would have an absolute veto. The Supreme Court was to have immediate jurisdiction over all lawsuits involving the United States, and state governors were to be appointed by the federal government.[101]

At the end of the convention, Hamilton was still not content with the final Constitution, but signed it anyway as a vast improvement over the Articles of Confederation, and urged his fellow delegates to do so also.[102] Since the other two members of the New York delegation, Lansing and Yates, had already withdrawn, Hamilton was the only New York signer to the United States Constitution.[94]: 206 He then took a highly active part in the successful campaign for the document's ratification in New York in 1788, which was a crucial step in its national ratification. He first used the popularity of the Constitution by the masses to compel George Clinton to sign, but was unsuccessful. The state convention in Poughkeepsie in June 1788 pitted Hamilton, Jay, James Duane, Robert Livingston, and Richard Morris against the Clintonian faction led by Melancton Smith, Lansing, Yates, and Gilbert Livingston.[103]

Clinton's faction wanted to amend the Constitution, while maintaining the state's right to secede if their attempts failed, and members of Hamilton's faction were against any conditional ratification, under the impression that New York would not be accepted into the Union. During the state convention, New Hampshire and Virginia becoming the ninth and tenth states to ratify the Constitution, respectively, had ensured any adjournment would not happen and a compromise would have to be reached.[103][104] Hamilton's arguments used for the ratifications were largely iterations of work from The Federalist Papers, and Smith eventually went for ratification, though it was more out of necessity than Hamilton's rhetoric.[104] The vote in the state convention was ratified 30 to 27, on July 26, 1788.[105]

The Federalist Papers

Hamilton recruited John Jay and James Madison to write The Federalist Papers, a series of essays, to defend the proposed Constitution. He made the largest contribution to that effort, writing 51 of the 85 essays published. Hamilton supervised the entire project, enlisted the participants, wrote the majority of the essays, and oversaw the publication. During the project, each person was responsible for their areas of expertise. Jay covered foreign relations. Madison covered the history of republics and confederacies, along with the anatomy of the new government. Hamilton covered the branches of government most pertinent to him: the executive and judicial branches, with some aspects of the Senate, as well as covering military matters and taxation.[106] The papers first appeared in The Independent Journal on October 27, 1787.[106]

Hamilton wrote the first paper signed as Publius, and all of the subsequent papers were signed under the name.[94]: 210 Jay wrote the next four papers to elaborate on the confederation's weakness and the need for unity against foreign aggression and against splitting into rival confederacies, and, except for No. 64, was not further involved.[107][94]: 211 Hamilton's highlights included discussion that although republics have been culpable for disorders in the past, advances in the "science of politics" had fostered principles that ensured that those abuses could be prevented, such as the division of powers, legislative checks and balances, an independent judiciary, and legislators that were represented by electors (No. 7–9).[107] Hamilton also wrote an extensive defense of the constitution (No. 23–36), and discussed the Senate and executive and judicial branches (No. 65–85). Hamilton and Madison worked to describe the anarchic state of the confederation (No. 15–22), and the two have been described as not being significantly different in thought during this time period—in contrast to their stark opposition later in life.[107] Subtle differences appeared with the two when discussing the necessity of standing armies.[107]

Treasury secretaryship (1789–1795)

In 1789, Washington—who had become the first president of the United States—appointed Hamilton to be his cabinet's Secretary of the Treasury on the advice of Robert Morris, Washington's initial pick.[108] On September 11, 1789, Hamilton was nominated and confirmed in the Senate[109] and sworn in the same day as the first United States Secretary of the Treasury.[110]

Report on Public Credit

Before the adjournment of the House in September 1789, they requested Hamilton to make a report on suggestions to improve the public credit by January 1790.[111] Hamilton had written to Morris as early as 1781, that fixing the public credit will win their objective of independence.[111] The sources that Hamilton used ranged from Frenchmen such as Jacques Necker and Montesquieu to British writers such as Hume, Hobbes, and Malachy Postlethwayt.[112] While writing the report he also sought out suggestions from contemporaries such as John Witherspoon and Madison. Although they agreed on additional taxes such as distilleries and duties on imported liquors and land taxes, Madison feared that the securities from the government debt would fall into foreign hands.[113][94]: 244–45

In the report, Hamilton felt that the securities should be paid at full value to their legitimate owners, including those who took the financial risk of buying government bonds that most experts thought would never be redeemed. He argued that liberty and property security were inseparable, and that the government should honor the contracts, as they formed the basis of public and private morality. To Hamilton, the proper handling of the government debt would also allow America to borrow at affordable interest rates and would also be a stimulant to the economy.[112]

Hamilton divided the debt into national and state, and further divided the national debt into foreign and domestic debt. While there was agreement on how to handle the foreign debt, especially with France, there was not with regards to the national debt held by domestic creditors. During the Revolutionary War, affluent citizens had invested in bonds, and war veterans had been paid with promissory notes and IOUs that plummeted in price during the Confederation. In response, the war veterans sold the securities to speculators for as little as fifteen to twenty cents on the dollar.[112][114]

Hamilton felt the money from the bonds should not go to the soldiers who had shown little faith in the country's future, but the speculators that had bought the bonds from the soldiers. The process of attempting to track down the original bondholders along with the government showing discrimination among the classes of holders if the war veterans were to be compensated also weighed in as factors for Hamilton. As for the state debts, Hamilton suggested consolidating them with the national debt and label it as federal debt, for the sake of efficiency on a national scale.[112]

The last portion of the report dealt with eliminating the debt by utilizing a sinking fund that would retire five percent of the debt annually until it was paid off. Due to the bonds being traded well below their face value, the purchases would benefit the government as the securities rose in price.[115]: 300 When the report was submitted to the House of Representatives, detractors soon began to speak against it. Some of the negative views expressed in the House were that the notion of programs that resembled British practice were wicked, and that the balance of power would be shifted away from the representatives to the executive branch. William Maclay suspected that several congressmen were involved in government securities, seeing Congress in an unholy league with New York speculators.[115]: 302 Congressman James Jackson also spoke against New York, with allegations of speculators attempting to swindle those who had not yet heard about Hamilton's report.[115]: 303

The involvement of those in Hamilton's circle such as Schuyler, William Duer, James Duane, Gouverneur Morris, and Rufus King as speculators was not favorable to those against the report, either, though Hamilton personally did not own or deal a share in the debt.[115]: 304 [94]: 250 Madison eventually spoke against it by February 1790. Although he was not against current holders of government debt to profit, he wanted the windfall to go to the original holders. Madison did not feel that the original holders had lost faith in the government but sold their securities out of desperation.[115]: 305 The compromise was seen as egregious to both Hamiltonians and their dissidents such as Maclay, and Madison's vote was defeated 36 votes to 13 on February 22.[115]: 305 [94]: 255

The fight for the national government to assume state debt was a longer issue and lasted over four months. During the period, the resources that Hamilton was to apply to the payment of state debts was requested by Alexander White, and was rejected due to Hamilton's not being able to prepare information by March 3, and was even postponed by his own supporters in spite of configuring a report the next day, which consisted of a series of additional duties to meet the interest on the state debts.[94]: 297–98 Duer resigned as Assistant Secretary of the Treasury, and the vote of assumption was voted down 31 votes to 29 on April 12.[94]: 258–59

During this period, Hamilton bypassed the rising issue of slavery in Congress, after Quakers petitioned for its abolition, returning to the issue the following year.[116]

Another issue in which Hamilton played a role was the temporary location of the capital from New York City. Tench Coxe was sent to speak to Maclay to bargain about the capital being temporarily located to Philadelphia, as a single vote in the Senate was needed and five in the House for the bill to pass.[94]: 263 Thomas Jefferson wrote years afterward that Hamilton had a discussion with him, around this time period, about the capital of the United States being relocated to Virginia by means of a "pill" that "would be peculiarly bitter to the Southern States, and that some concomitant measure should be adopted to sweeten it a little to them".[94]: 263 The bill passed in the Senate on July 21 and in the House 34 votes to 28 on July 26, 1790.[94]: 263

Report on a National Bank

Hamilton's Report on a National Bank was a projection from the first Report on the Public Credit. Although Hamilton had been forming ideas of a national bank as early as 1779,[94]: 268 he had gathered ideas in various ways over the past eleven years. These included theories from Adam Smith,[117] extensive studies on the Bank of England, the blunders of the Bank of North America and his experience in establishing the Bank of New York.[118] He also used American records from James Wilson, Pelatiah Webster, Gouverneur Morris, and from his assistant treasury secretary Tench Coxe.[118] He thought that this plan for a National Bank could help in any sort of financial crisis.[119]

Hamilton suggested that Congress should charter the national bank with a capitalization of $10 million, one-fifth of which would be handled by the government. Since the government did not have the money, it would borrow the money from the bank itself, and repay the loan in ten even annual installments.[44]: 194 The rest was to be available to individual investors.[120] The bank was to be governed by a twenty-five-member board of directors that was to represent a large majority of the private shareholders, which Hamilton considered essential for his being under a private direction.[94]: 268 Hamilton's bank model had many similarities to that of the Bank of England, except Hamilton wanted to exclude the government from being involved in public debt, but provide a large, firm, and elastic money supply for the functioning of normal businesses and usual economic development, among other differences.[44]: 194–95 The tax revenue to initiate the bank was the same as he had previously proposed, increases on imported spirits: rum, liquor, and whiskey.[44]: 195–96

The bill passed through the Senate practically without a problem, but objections to the proposal increased by the time it reached the House of Representatives. It was generally held by critics that Hamilton was serving the interests of the Northeast by means of the bank,[121] and those of the agrarian lifestyle would not benefit from it.[94]: 270 Among those critics was James Jackson of Georgia, who also attempted to refute the report by quoting from The Federalist Papers.[94]: 270 Madison and Jefferson also opposed the bank bill. The potential of the capital not being moved to the Potomac if the bank was to have a firm establishment in Philadelphia was a more significant reason, and actions that Pennsylvania members of Congress took to keep the capital there made both men anxious.[44]: 199–200 The Whiskey Rebellion also showed how in other financial plans, there was a distance between the classes as the wealthy profited from the taxes.[122]

Madison warned the Pennsylvania congress members that he would attack the bill as unconstitutional in the House, and followed up on his threat.[44]: 200 Madison argued his case of where the power of a bank could be established within the Constitution, but he failed to sway members of the House, and his authority on the constitution was questioned by a few members.[44]: 200–01 The bill eventually passed in an overwhelming fashion 39 to 20, on February 8, 1791.[94]: 271

Washington hesitated to sign the bill, as he received suggestions from Attorney General Edmund Randolph and Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson dismissed the Necessary and Proper Clause as reasoning for the creation of a national bank, stating that the enumerated powers "can all be carried into execution without a bank."[94]: 271–72 Along with Randolph and Jefferson's objections, Washington's involvement in the movement of the capital from Philadelphia is also thought to be a reason for his hesitation.[44]: 202–03 In response to the objection of the clause, Hamilton stated that "Necessary often means no more than needful, requisite, incidental, useful, or conductive to", and the bank was a "convenient species of medium in which [taxes] are to be paid."[94]: 272–73 Washington would eventually sign the bill into law.[94]: 272–73

Establishing the mint

In 1791, Hamilton submitted the Report on the Establishment of a Mint to the House of Representatives. Many of Hamilton's ideas for this report were from European economists, resolutions from the 1785 and 1786 Continental Congress meetings, and people such as Robert Morris, Gouverneur Morris and Thomas Jefferson.[44]: 197 [123]

Because the most circulated coins in the United States at the time were Spanish currency, Hamilton proposed that minting a United States dollar weighing almost as much as the Spanish peso would be the simplest way to introduce a national currency.[124] Hamilton differed from European monetary policymakers in his desire to overprice gold relative to silver, on the grounds that the United States would always receive an influx of silver from the West Indies.[44]: 197 Despite his own preference for a monometallic gold standard,[125] he ultimately issued a bimetallic currency at a fixed 15:1 ratio of silver to gold.[44]: 197 [126][127]

Hamilton proposed that the U.S. dollar should have fractional coins using decimals, rather than eighths like the Spanish coinage.[128] This innovation was originally suggested by Superintendent of Finance Robert Morris, with whom Hamilton corresponded after examining one of Morris's Nova Constellatio coins in 1783.[129] He also desired the minting of small value coins, such as silver ten-cent and copper cent and half-cent pieces, for reducing the cost of living for the poor.[44]: 198 [118] One of his main objectives was for the general public to become accustomed to handling money on a frequent basis.[44]: 198

By 1792, Hamilton's principles were adopted by Congress, resulting in the Coinage Act of 1792, and the creation of the mint. There was to be a ten-dollar gold Eagle coin, a silver dollar, and fractional money ranging from one-half to fifty cents.[125] The coining of silver and gold was issued by 1795.[125]

Revenue Cutter Service

Smuggling off American coasts was an issue before the Revolutionary War, and after the Revolution it was more problematic. Along with smuggling, lack of shipping control, pirating, and a revenue unbalance were also major problems.[130] In response, Hamilton proposed to Congress to enact a naval police force called revenue cutters in order to patrol the waters and assist the custom collectors with confiscating contraband.[131] This idea was also proposed to assist in tariff controlling, boosting the American economy, and promote the merchant marine.[130] It is thought that his experience obtained during his apprenticeship with Nicholas Kruger was influential in his decision-making.[132]

Concerning some of the details of the System of Cutters,[133] Hamilton wanted the first ten cutters in different areas in the United States, from New England to Georgia.[131][134] Each of those cutters was to be armed with ten muskets and bayonets, twenty pistols, two chisels, one broad-ax and two lanterns. The fabric of the sails was to be domestically manufactured;[131] and provisions were made for the employees' food supply and etiquette when boarding ships.[131] Congress established the Revenue Cutter Service on August 4, 1790, which is viewed as the birth of the United States Coast Guard.[130]

Whiskey as tax revenue

One of the principal sources of revenue Hamilton prevailed upon Congress to approve was an excise tax on whiskey. In his first Tariff Bill in January 1790, Hamilton proposed to raise the three million dollars needed to pay for government operating expenses and interest on domestic and foreign debts by means of an increase on duties on imported wines, distilled spirits, tea, coffee, and domestic spirits. It failed, with Congress complying with most recommendations excluding the excise tax on whiskey. The same year, Madison modified Hamilton's tariff to involve only imported duties; it was passed in September.[135]

In response of diversifying revenues, as three-fourths of revenue gathered was from commerce with Great Britain, Hamilton attempted once again during his Report on Public Credit when presenting it in 1790 to implement an excise tax on both imported and domestic spirits.[136][137] The taxation rate was graduated in proportion to the whiskey proof, and Hamilton intended to equalize the tax burden on imported spirits with imported and domestic liquor.[137] In lieu of the excise on production citizens could pay 60 cents by the gallon of dispensing capacity, along with an exemption on small stills used exclusively for domestic consumption.[137] He realized the loathing that the tax would receive in rural areas, but thought of the taxing of spirits more reasonable than land taxes.[136]

Opposition initially came from Pennsylvania's House of Representatives protesting the tax. William Maclay had noted that not even the Pennsylvanian legislators had been able to enforce excise taxes in the western regions of the state.[136] Hamilton was aware of the potential difficulties and proposed inspectors the ability to search buildings that distillers were designated to store their spirits, and would be able to search suspected illegal storage facilities to confiscate contraband with a warrant.[138] Although the inspectors were not allowed to search houses and warehouses, they were to visit twice a day and file weekly reports in extensive detail.[136] Hamilton cautioned against expedited judicial means, and favored a jury trial with potential offenders.[138] As soon as 1791, locals began to shun or threaten inspectors, as they felt the inspection methods were intrusive.[136] Inspectors were also tarred and feathered, blindfolded, and whipped. Hamilton had attempted to appease the opposition with lowered tax rates, but it did not suffice.[139]

Strong opposition to the whiskey tax by cottage producers in remote, rural regions erupted into the Whiskey Rebellion in 1794; in Western Pennsylvania and western Virginia, whiskey was the basic export product and was fundamental to the local economy. In response to the rebellion, believing compliance with the laws was vital to the establishment of federal authority, Hamilton accompanied to the rebellion's site President Washington, General Henry "Light Horse Harry" Lee, and more federal troops than were ever assembled in one place during the Revolution. This overwhelming display of force intimidated the leaders of the insurrection, ending the rebellion virtually without bloodshed.[140]

Manufacturing and industry

Hamilton's next report was his Report on Manufactures. Although he was requested by Congress on January 15, 1790, for a report for manufacturing that would expand the United States' independence, the report was not submitted until December 5, 1791.[94]: 274, 277 In the report, Hamilton quoted from Wealth of Nations and used the French physiocrats as an example for rejecting agrarianism and the physiocratic theory, respectively.[44]: 233 Hamilton also refuted Smith's ideas of government noninterference, as it would have been detrimental for trade with other countries.[44]: 244 Hamilton also thought that the United States, being a primarily agrarian country, would be at a disadvantage in dealing with Europe.[141] In response to the agrarian detractors, Hamilton stated that the agriculturists' interest would be advanced by manufactures,[94]: 276 and that agriculture was just as productive as manufacturing.[44]: 233 [94]: 276

Hamilton argued that developing an industrial economy is impossible without protective tariffs.[142] Among the ways that the government should assist manufacturing, Hamilton argued for government assistance to "infant industries" so they can achieve economies of scale, by levying protective duties on imported foreign goods that were also manufactured in the United States,[143] for withdrawing duties levied on raw materials needed for domestic manufacturing,[94]: 277 [143] and pecuniary boundaries.[94]: 277 He also called for encouraging immigration for people to better themselves in similar employment opportunities.[143][144] Congress shelved the report without much debate, except for Madison's objection to Hamilton's formulation of the general welfare clause, which Hamilton construed liberally as a legal basis for his extensive programs.[145]

In 1791, Hamilton, along with Coxe and several entrepreneurs from New York City and Philadelphia formed the Society for the Establishment of Useful Manufactures, a private industrial corporation. In May 1792, the directors decided to examine the Great Falls of the Passaic River in New Jersey as a possible location for a manufacturing center. On July 4, 1792, the society directors met Philip Schuyler at Abraham Godwin's hotel on the Passaic River, where they led a tour prospecting the area for the national manufactory. It was originally suggested that they dig mile-long trenches and build the factories away from the falls, but Hamilton argued that it would be too costly and laborious.[146]

The location at Great Falls of the Passaic River in New Jersey was selected due to access to raw materials, it being densely inhabited, and having access to water power from the falls of the Passaic.[44]: 231 The factory town was named Paterson after New Jersey's Governor William Paterson, who signed the charter.[44]: 232 [147] The profits were to derive from specific corporates rather than the benefits to be conferred to the nation and the citizens, which was unlike the report.[148] Hamilton also suggested the first stock to be offered at $500,000 and to eventually increase to $1 million, and welcomed state and federal government subscriptions alike.[94]: 280 [148] The company was never successful, with numerous shareholders reneged on stock payments and some going bankrupt. William Duer, the governor of the program, was sent to debtors' prison, where he died.[149] In spite of Hamilton's efforts to mend the disaster, the company folded.[147]

Jay Treaty

When France and Britain went to war in early 1793, all four members of the Cabinet were consulted on what to do. They and Washington unanimously agreed to remain neutral, and to have the French ambassador who was raising privateers and mercenaries on American soil, Edmond-Charles Genêt, recalled.[150]: 336–41 However, in 1794, policy toward Britain became a major point of contention between the two parties. Hamilton and the Federalists wished for more trade with Britain, the largest trading partner of the newly formed United States. The Republicans saw monarchist Britain as the main threat to republicanism and proposed instead to start a trade war.[94]: 327–28

To avoid war, Washington sent Chief Justice John Jay to negotiate with the British, with Hamilton largely writing Jay's instructions. The result was a treaty denounced by the Republicans, but Hamilton mobilized support throughout the land.[151] The Jay Treaty passed the Senate in 1795 by exactly the required two-thirds majority. The treaty resolved issues remaining from the Revolution, averted war, and made possible ten years of peaceful trade between the United States and Britain.[150]: Ch 9 Historian George Herring notes the "remarkable and fortuitous economic and diplomatic gains" produced by the Treaty.[152]

Several European states had formed the Second League of Armed Neutrality against incursions on their neutral rights; the cabinet was also consulted on whether the United States should join the alliance and decided not to. It kept that decision secret, but Hamilton revealed it in private to George Hammond, the British minister to the United States, without telling Jay or anyone else. His act remained unknown until Hammond's dispatches were read in the 1920s. This revelation may have had limited effect on the negotiations; Jay did threaten to join the League at one point, but the British had other reasons not to view the alliance as a serious threat.[150]: 411 ff [153]

Resignation from public office

Hamilton's wife suffered a miscarriage[154] while he was absent during his armed repression of the Whiskey Rebellion.[155] In the wake of this, Hamilton tendered his resignation from office on December 1, 1794, giving Washington two months' notice,[156] Before leaving his post on January 31, 1795, Hamilton submitted the Report on a Plan for the Further Support of Public Credit to Congress to curb the debt problem. Hamilton grew dissatisfied with what he viewed as a lack of a comprehensive plan to fix the public debt. He wished to have new taxes passed with older ones made permanent and stated that any surplus from the excise tax on liquor would be pledged to lower public debt. His proposals were included in a bill by Congress within slightly over a month after his departure as treasury secretary.[157] Some months later, Hamilton resumed his law practice in New York to remain closer to his family.[158]

Emergence of political parties

Hamilton's vision was challenged by Virginia agrarians Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, who formed the Democratic-Republican Party. They favored strong state governments based in rural America and protected by state militias as opposed to a strong national government supported by a national army and navy. They denounced Hamilton as insufficiently devoted to republicanism, too friendly toward corrupt Britain and the monarchy in general, and too oriented toward cities, business and banking.[159]

The two-party system began to emerge as political parties coalesced around competing interests. A congressional caucus, led by Madison, Jefferson, and William Branch Giles, began as an opposition group to Hamilton's financial programs. Hamilton and his allies began to call themselves the Federalists.[160][161]

Hamilton assembled a nationwide coalition to garner support for the administration, including the expansive financial programs Hamilton had made administration policy and especially the president's policy of neutrality in the European war between Britain and France. Hamilton publicly denounced French minister Genêt, who commissioned American privateers and recruited Americans for private militias to attack British ships and colonial possessions of British allies. Eventually, even Jefferson joined Hamilton in seeking Genêt's recall.[162] If Hamilton's administrative republic was to succeed, Americans had to see themselves first as citizens of a nation and experience an administration that proved firm and demonstrated the concepts found within the Constitution.[163] The Federalists did impose some internal direct taxes, but they departed from most implications of Hamilton's administrative republic as risky.[164]

The Republicans opposed banks and cities and favored the series of unstable revolutionary governments in France. They built their own national coalition to oppose the Federalists. Both sides gained the support of local political factions, and each side developed its own partisan newspapers. Noah Webster, John Fenno, and William Cobbett were energetic editors for the Federalists, while Benjamin Franklin Bache and Philip Freneau were fiery Republican editors. All of their newspapers were characterized by intense personal attacks, major exaggerations, and invented claims. In 1801, Hamilton established a daily newspaper, the New York Evening Post, and brought in William Coleman as its editor.[165] Hamilton's and Jefferson's incompatibility was heightened by the unavowed wish of each to be Washington's principal and most trusted advisor.[166]

An additional partisan irritant to Hamilton was the 1791 United States Senate election in New York, which resulted in the election of Democratic-Republican candidate Aaron Burr over Federalist candidate Philip Schuyler, the incumbent and Hamilton's father-in-law. Hamilton blamed Burr personally for this outcome, and negative characterizations of Burr began to appear in his correspondence thereafter. The two men did work together from time to time thereafter on various projects, including Hamilton's army of 1798 and the Manhattan Water Company.[167]

Post-secretaryship (1795–1804)

1796 presidential election

Hamilton's resignation as secretary of the treasury in 1795 did not remove him from public life. With the resumption of his law practice, he remained close to Washington as an advisor and friend. Hamilton influenced Washington in the composition of his farewell address by writing drafts for Washington to compare with the latter's draft, although when Washington contemplated retirement in 1792, he had consulted Madison for a draft that was used in a similar manner to Hamilton's.[168][169]

In the election of 1796, under the Constitution as it stood then, each of the presidential electors had two votes, which they were to cast for different men from different states. The one who received the most votes would become president, the second-most, vice president. This system was not designed with the operation of parties in mind, as they had been thought disreputable and factious. The Federalists planned to deal with this by having all their electors vote for John Adams, then vice president, and all but a few for Thomas Pinckney.[170]

Adams resented Hamilton's influence with Washington and considered him overambitious and scandalous in his private life; Hamilton compared Adams unfavorably with Washington and thought him too emotionally unstable to be president.[171] Hamilton took the election as an opportunity: he urged all the northern electors to vote for Adams and Pinckney, lest Jefferson get in; but he cooperated with Edward Rutledge to have South Carolina's electors vote for Jefferson and Pinckney. If all this worked, Pinckney would have more votes than Adams, Pinckney would become president, and Adams would remain vice president, but it did not work. The Federalists found out about it and northern Federalists voted for Adams but not for Pinckney, in sufficient numbers that Pinckney came in third and Jefferson became vice president.[172] Adams resented the intrigue since he felt his service to the nation was much more extensive than Pinckney's.[173]

Reynolds affair

In the summer of 1797, Hamilton became the first major American politician publicly involved in a sex scandal.[174] Six years earlier, in the summer of 1791, 34-year-old Hamilton became involved in an affair with 23-year-old Maria Reynolds. According to Hamilton's account Maria approached him at his house in Philadelphia, claiming that her husband James Reynolds was abusive and had abandoned her, and she wished to return to her relatives in New York but lacked the means.[94]: 366–69 Hamilton recorded her address and subsequently delivered $30 personally to her boarding house, where she led him into her bedroom and "Some conversation ensued from which it was quickly apparent that other than pecuniary consolation would be acceptable". The two began an intermittent illicit affair that lasted approximately until June 1792.[175]

Over the course of that year, while the affair was taking place, James Reynolds was well aware of his wife's infidelity, and likely orchestrated it from the beginning. He continually supported their relationship to extort blackmail money regularly from Hamilton. The common practice of the day for men of equal social standing was for the wronged husband to seek retribution in a duel, but Reynolds, of a lower social status and realizing how much Hamilton had to lose if his activity came into public view, resorted to extortion.[176] After an initial request of $1,000[177] to which Hamilton complied, Reynolds invited Hamilton to renew his visits to his wife "as a friend"[178] only to extort forced "loans" after each visit that, most likely in collusion, Maria solicited with her letters. In the end, the blackmail payments totaled over $1,300 including the initial extortion.[94]: 369 Hamilton at this point may have been aware of both spouses being involved in the blackmail,[179] and he welcomed and strictly complied with James Reynolds' eventual request to end the affair.[175][180]

In November 1792, James Reynolds and his associate Jacob Clingman were arrested for counterfeiting and speculating in Revolutionary War veterans' unpaid back wages. Clingman was released on bail and relayed information to Democratic-Republican congressman James Monroe that Reynolds had evidence incriminating Hamilton in illicit activity as Treasury Secretary. Monroe consulted with congressmen Muhlenberg and Venable on what actions to take and the congressmen confronted Hamilton on December 15, 1792.[175] Hamilton refuted the suspicions of financial speculation by exposing his affair with Maria and producing as evidence the letters by both of the Reynolds, proving that his payments to James Reynolds related to blackmail over his adultery, and not to treasury misconduct. The trio agreed on their honor to keep the documents privately with the utmost confidence.[94]: 366–69

Five years later however, in the summer of 1797, the "notoriously scurrilous" journalist James T. Callender published A History of the United States for the Year 1796.[44]: 334 The pamphlet contained accusations based on documents from the confrontation of December 15, 1792, taken out of context, that James Reynolds had been an agent of Hamilton. On July 5, 1797, Hamilton wrote to Monroe, Muhlenberg, and Venable, asking them to confirm that there was nothing that would damage the perception of his integrity while Secretary of Treasury. All but Monroe complied with Hamilton's request. Hamilton then published a 100-page booklet, later usually referred to as the Reynolds Pamphlet, and discussed the affair in indelicate detail for the time. Hamilton's wife Elizabeth eventually forgave him, but never forgave Monroe.[181] Although Hamilton faced ridicule from the Democratic-Republican faction, he maintained his availability for public service.[44]: 334–36

Quasi-War

During the military build-up of the Quasi-War with France, and with the strong endorsement of Washington, Adams reluctantly appointed Hamilton a major general of the army. At Washington's insistence, Hamilton was made the senior major general, prompting Continental Army major general Henry Knox to decline the appointment to serve as Hamilton's junior, believing it would be degrading to serve beneath him.[182][183]

Hamilton served as inspector general of the United States Army from July 18, 1798, to June 15, 1800. Because Washington was unwilling to leave Mount Vernon unless it were to command an army in the field, Hamilton was the de facto head of the army, to Adams's considerable displeasure. If full-scale war broke out with France, Hamilton argued that the army should conquer the North American colonies of France's ally, Spain, bordering the United States.[184] Hamilton was prepared to march the army through the Southern United States if necessary.[185]

To fund this army, Hamilton wrote regularly to Oliver Wolcott Jr., his successor at the treasury, Representative William Loughton Smith, and U.S. senator Theodore Sedgwick. He urged them to pass a direct tax to fund the war. Smith resigned in July 1797, as Hamilton complained to him for slowness, and urged Wolcott to tax houses instead of land.[186] The eventual program included taxes on land, houses, and slaves, calculated at different rates in different states and requiring assessment of houses, and a stamp act like that of the British before the Revolution, though this time Americans were taxing themselves through their own representatives.[187] This provoked resistance in southeastern Pennsylvania nevertheless, led primarily by men such as John Fries who had marched with Washington against the Whiskey Rebellion.[188]

Hamilton aided in all areas of the army's development, and after Washington's death he was by default the senior officer of the United States Army from December 14, 1799, to June 15, 1800. The army was to guard against invasion from France. Adams, however, derailed all plans for war by opening negotiations with France that led to peace.[189] There was no longer a direct threat for the army Hamilton was commanding to respond to.[190] Adams discovered that key members of his cabinet, namely Secretary of State Timothy Pickering and Secretary of War James McHenry, were more loyal to Hamilton than himself; Adams fired them in May 1800.[191]

1800 presidential election

In November 1799, the Alien and Sedition Acts had left one Democratic-Republican newspaper functioning in New York City. When the last newspaper, the New Daily Advertiser, reprinted an article saying that Hamilton had attempted to purchase the Philadelphia Aurora to close it down, and said the purchase could have been funded by "British secret service money". Hamilton urged the New York Attorney General to prosecute the publisher for seditious libel, and the prosecution compelled the owner to close the paper.[192]

In the 1800 election, Hamilton worked to defeat not only the Democratic-Republicans, but also his party's own nominee, John Adams.[94]: 392–99 Aaron Burr had won New York for Jefferson in May via the New York City legislative elections, as the legislature was to choose New York's electors; now Hamilton proposed a direct election, with carefully drawn districts where each district's voters would choose an elector—such that the Federalists would split the electoral vote of New York. Jay, who had resigned from the Supreme Court to be governor of New York, wrote on the back of a letter, "Proposing a measure for party purposes which it would not become me to adopt," and declined to reply.[193]

Adams was running this time with Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, the elder brother of former vice presidential candidate Thomas. Hamilton toured New England, again urging northern electors to hold firm for Pinckney in the renewed hope of making Pinckney president; and he again intrigued in South Carolina.[44]: 350–51 Hamilton's ideas involved coaxing middle-state Federalists to assert their non-support for Adams if there was no support for Pinckney and writing to more of the modest supports of Adams concerning his supposed misconduct while president.[44]: 350–51 Hamilton expected to see southern states such as the Carolinas cast their votes for Pinckney and Jefferson, and would result in the former being ahead of both Adams and Jefferson.[94]: 394–95

In accordance with the second of the aforementioned plans, and a recent personal rift with Adams,[44]: 351 Hamilton wrote a pamphlet called Letter from Alexander Hamilton, Concerning the Public Conduct and Character of John Adams, Esq. President of the United States that was highly critical of him, though it closed with a tepid endorsement.[94]: 396

Jefferson had beaten Adams, but both he and Aaron Burr had received 73 votes in the Electoral College. With Jefferson and Burr tied, the House of Representatives had to choose between the two men.[44]: 352 [94]: 399 Several Federalists who opposed Jefferson supported Burr, and for the first 35 ballots, Jefferson was denied a majority. Before the 36th ballot, Hamilton threw his weight behind Jefferson, supporting the arrangement reached by James A. Bayard of Delaware, in which five Federalist representatives from Maryland and Vermont abstained from voting, allowing those states' delegations to go for Jefferson, ending the impasse and electing Jefferson president rather than Burr.[44]: 350–51

Even though Hamilton did not like Jefferson and disagreed with him on many issues, he viewed Jefferson as the lesser of two evils. Hamilton spoke of Jefferson as being "by far not so a dangerous man" and of Burr as a "mischievous enemy" to the principal measure of the past administration.[194] It was for that reason, along with the fact that Burr was a northerner and not a Virginian, that many Federalist representatives voted for him.[195][contradictory]

Hamilton wrote many letters to friends in Congress to convince the members to see otherwise.[44]: 352 [94]: 401 In the end, Burr would become vice president after losing to Jefferson.[196] However, according to several historians, the Federalists had rejected Hamilton's diatribe as reasons to not vote for Burr.[44]: 353 [94]: 401 In his book American Machiavelli: Alexander Hamilton and the Origins of US Foreign Policy, historian John Lamberton Harper stated Hamilton could have "perhaps" contributed "to a degree" in Burr's defeat.[197] Ron Chernow, alternatively, claimed that Hamilton "squelched" Burr's chance at becoming president.[198] When it became clear that Jefferson had developed his own concerns about Burr and would not support his return to the vice presidency,[196] Burr sought the New York governorship in 1804 with Federalist support, against the Jeffersonian Morgan Lewis, but was defeated by forces including Hamilton.[199]

Duel with Burr and death

Soon after Lewis' gubernatorial victory, the Albany Register published Charles D. Cooper's letters, citing Hamilton's opposition to Burr and alleging that Hamilton had expressed "a still more despicable opinion" of the vice president at an upstate New York dinner party.[200][201] Cooper claimed that the letter was intercepted after relaying the information, but stated he was "unusually cautious" in recollecting the information from the dinner.[202]

Burr, sensing an attack on his honor, and recovering from his defeat, demanded an apology in the form of a letter. Hamilton wrote a letter in response and ultimately refused because he could not recall the instance of insulting Burr. Hamilton would also have been accused of recanting Cooper's letter out of cowardice.[94]: 423–24 After a series of attempts to reconcile were to no avail, a duel was arranged through liaisons on June 27, 1804.[94]: 426

The concept of honor was fundamental to Hamilton's vision of himself and of the nation.[203] Historians have noted, as evidence of the importance that honor held in Hamilton's value system, that Hamilton had previously been a party to seven "affairs of honor" as a principal, and to three as an advisor or second.[204] Such affairs of honor were often concluded prior to reaching the final stage of a duel.[204]

Before the duel, Hamilton wrote an explanation of his decision to participate while at the same time intending to "throw away" his shot.[205] His desire to be available for future political matters also played a factor.[200] A week before the duel, at an annual Independence Day dinner of the Society of the Cincinnati, both Hamilton and Burr were in attendance. Separate accounts confirm that Hamilton was uncharacteristically effusive while Burr was, by contrast, uncharacteristically withdrawn. Accounts also agree that Burr became roused when Hamilton, again uncharacteristically, sang a favorite song, which recent scholarship indicates that it was "How Stands the Glass Around", an anthem sung by military troops about fighting and dying in war.[206]

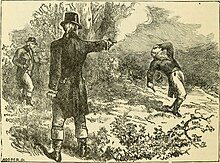

The duel began at dawn on July 11, 1804, along the west bank of the Hudson River on a rocky ledge in Weehawken, New Jersey.[207] Both opponents were rowed over from Manhattan separately from different locations, as the spot was not accessible from the west due to the steepness of the adjoining cliffs. Coincidentally, the duel took place relatively close to the location of the duel that had ended the life of Hamilton's eldest son, Philip, three years earlier.[208] Lots were cast for the choice of position and which second should start the duel. Both were won by Hamilton's second, who chose the upper edge of the ledge for Hamilton facing the city to the east, toward the rising sun.[209] After the seconds had measured the paces Hamilton, according to both William P. Van Ness and Burr, raised his pistol "as if to try the light" and had to wear his glasses to prevent his vision from being obscured.[210] Hamilton also refused the more sensitive hairspring setting for the dueling pistols offered by Nathaniel Pendleton, and Burr was unaware of the option.[211]

Vice President Burr shot Hamilton, delivering what proved to be a fatal wound. Hamilton's shot was said to have broken a tree branch directly above Burr's head.[170] Neither of the seconds, Pendleton nor Van Ness, could determine who fired first,[212] as each claimed that the other man had fired first.[211]

Soon after, they measured and triangulated the shooting, but could not determine from which angle Hamilton had fired. Burr's shot hit Hamilton in the lower abdomen above his right hip. The bullet ricocheted off Hamilton's second or third false rib, fracturing it and causing considerable damage to his internal organs, particularly his liver and diaphragm, before becoming lodged in his first or second lumbar vertebra.[94]: 429 [213] The biographer Ron Chernow considers the circumstances to indicate that, after taking deliberate aim, Burr fired second,[214] while the biographer James Earnest Cooke suggests that Burr took careful aim and shot first, and Hamilton fired while falling, after being struck by Burr's bullet.[215]

The paralyzed Hamilton was immediately attended by the same surgeon who tended Philip Hamilton, and ferried to the Greenwich Village boarding house of his friend William Bayard Jr., who had been waiting on the dock.[216] On his deathbed, Hamilton asked the Episcopal Bishop of New York, Benjamin Moore, to give him holy communion.[217] Moore initially declined to do so on the grounds that participating in a duel was a mortal sin and that Hamilton, although undoubtedly sincere in his faith, was not a member of the Episcopalian denomination.[218] After leaving, Moore was persuaded to return that afternoon by the urgent pleas of Hamilton's friends. Upon receiving Hamilton's solemn assurance that he repented for his part in the duel, Moore gave him communion.[218]

After final visits from his family, friends, and considerable suffering for at least 31 hours, Hamilton died at two o'clock the following afternoon, July 12, 1804,[216][219] at Bayard's home just below the present Gansevoort Street.[220] The city fathers halted all business at noon two days later for Hamilton's funeral. The procession route of about two miles organized by the Society of the Cincinnati had so many participants of every class of citizen that it took hours to complete and was widely reported nationwide by newspapers.[221] Moore conducted the funeral service at Trinity Church.[217] Gouverneur Morris gave the eulogy and secretly established a fund to support his widow and children.[222] Hamilton was buried in the church's cemetery.[223]

Religion

Religious faith

As a youth in the West Indies, Hamilton was an orthodox and conventional Presbyterian of the New Lights; he was mentored there by a former student of John Witherspoon, a moderate of the New School.[224] He wrote two or three hymns, which were published in the local newspaper.[225] Robert Troup, his college roommate, noted that Hamilton was "in the habit of praying on his knees night and morning".[226]: 10

According to Gordon Wood, Hamilton dropped his youthful religiosity during the Revolution and became "a conventional liberal with theistic inclinations who was an irregular churchgoer at best"; however, he returned to religion in his last years.[227] Chernow wrote that Hamilton was nominally an Episcopalian, but:

[H]e was not clearly affiliated with the denomination and did not seem to attend church regularly or take communion. Like Adams, Franklin, and Jefferson, Hamilton had probably fallen under the sway of deism, which sought to substitute reason for revelation and dropped the notion of an active God who intervened in human affairs. At the same time, he never doubted God's existence, embracing Christianity as a system of morality and cosmic justice.[228]

Stories were circulated that Hamilton had made two quips about God at the time of the Constitutional Convention in 1787.[229] During the French Revolution, he displayed a utilitarian approach to using religion for political ends, such as by maligning Jefferson as "the atheist", and insisting that Christianity and Jeffersonian democracy were incompatible.[229]: 316 After 1801, Hamilton further attested his belief in Christianity, proposing a Christian Constitutional Society in 1802 to take hold of "some strong feeling of the mind" to elect "fit men" to office, and advocating "Christian welfare societies" for the poor. After being shot, Hamilton spoke of his belief in God's mercy.[d]