Swiss People's Party

| |

| President | Marcel Dettling |

| Members in Federal Council | Albert Rösti Guy Parmelin |

| Founded | 22 September 1971 |

| Merger of | |

| Headquarters | Brückfeldstrasse 18, 3001 Bern |

| Youth wing | Young SVP |

| Membership (2015) | 90,000[1] |

| Ideology | |

| Political position | Right-wing[12] |

| European affiliation | None[note 1] |

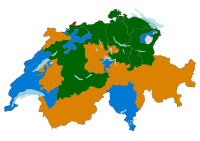

| Colours | Green |

| Slogan | "Swiss quality, the party of the middle class." |

| Federal Council | 2 / 7 |

| National Council | 62 / 200 |

| Council of States | 6 / 46 |

| Cantonal executives | 23 / 154 |

| Cantonal legislatures | 590 / 2,609 |

| Website | |

| svp | |

The Swiss People's Party (German: Schweizerische Volkspartei, SVP; Romansh: Partida populara Svizra, PPS), also known as the Democratic Union of the Centre (French: Union démocratique du centre, UDC; Italian: Unione Democratica di Centro, UDC), is a national conservative[13][14] and right-wing populist[15] political party in Switzerland. Chaired by Marcel Dettling, it is the largest party in the Federal Assembly, with 62 members of the National Council[16] and 6 of the Council of States.

The SVP originated in 1971 as a merger of the Party of Farmers, Traders and Independents (BGB) and the Democratic Party, while the BGB, in turn, had been founded in the context of the emerging local farmers' parties in the late 1910s. The SVP initially did not enjoy any increased support beyond that of the BGB, retaining around 11% of the vote through the 1970s and 1980s. This changed however during the 1990s, when the party underwent deep structural and ideological changes under the influence of Christoph Blocher; the SVP then became the strongest party in Switzerland by the 2000s.[17]

In line with the changes fostered by Blocher, the party started to focus increasingly on issues such as Euroscepticism[18] and opposition to mass immigration.[19] Its vote share of 28.9% in the 2007 federal election was the highest vote ever recorded for a single party in Switzerland[20] until 2015, when it surpassed its own record with 29.4%.[21] Blocher's failure to win re-election as a Federal Councillor led to moderates within the party splitting to form the Conservative Democratic Party (BDP), which later merged with the Christian Democratic People's Party into The Centre. As of 2024[update], the party is the largest in the National Council with 62 seats. It has six seats in the Council of States.[22]

History

[edit]Background, farmers' parties

[edit]The early origins of the SVP go back to the late 1910s, when numerous cantonal farmers' parties were founded in agrarian, Protestant, German-speaking parts of Switzerland. While the Free Democratic Party had earlier been a popular party for farmers, this changed during World War I when the party had mainly defended the interests of industrialists and consumer circles.[23] When proportional representation was introduced in 1919, the new farmers' parties won significant electoral support, especially in Zürich and Bern, and eventually also gained representation in parliament and government.[24] By 1929, the coalition of farmers' parties had gained enough influence to get one of their leaders, Rudolf Minger, elected to the Federal Council.

In 1936, a representative party was founded on the national level, called the Party of Farmers, Traders and Independents (BGB). During the 1930s, the BGB entered the mainstream of Swiss politics as a right-wing conservative party in the bourgeois bloc. While the party opposed any kind of socialist ideas such as internationalism and anti-militarism, it sought to represent local Swiss traders and farmers against big business and international capital.[24]

The BGB contributed strongly to the establishment of the Swiss national ideology known as the Geistige Landesverteidigung (Spiritual Defence of the Nation), which was largely responsible for the growing Swiss sociocultural and political cohesion from the 1930s. In the party's fight against left-wing ideologies, sections of party officials and farmers voiced sympathy with, or failed to distance themselves from, emerging fascist movements.[25] After World War II, the BGB contributed to the establishment of the characteristic Swiss post-war consensual politics, social agreements and economic growth policies. The party continued to be a reliable political partner with the Swiss Conservative People's Party and the Free Democratic Party.[26]

Early years (1971–1980s)

[edit]In 1971, the BGB changed its name to the Swiss People's Party (SVP) after it merged with the Democratic Party from Glarus and Grisons.[27] The Democratic Party had been supported particularly by workers, and the SVP sought to expand its electoral base towards these, as the traditional BGB base in the rural population had started to lose its importance in the post-war era. As the Democratic Party had represented centrist, social-liberal positions, the course of the SVP shifted towards the political centre following internal debates.[28] The new party however continued to see its level of support at around 11%, the same as the former BGB throughout the post-war era. Internal debates continued, and the 1980s saw growing conflicts between the Bern and Zürich cantonal branches, where the former branch represented the centrist faction, and the latter looked to put new issues on the political agenda.[28]

When the young entrepreneur Christoph Blocher was elected president of the Zürich SVP in 1977, he declared his intent to oversee significant change in the political line of the Zürich SVP, bringing an end to debates that aimed to open the party up to a wide array of opinions. Blocher soon consolidated his power in Zürich, and began to renew the organisational structures, activities, campaigning style and political agenda of the local branch.[29] The young members of the party was boosted with the establishment of a cantonal Young SVP (JSVP) in 1977, as well as political training courses. The ideology of the Zürich branch was also reinforced, and the rhetoric hardened, which resulted in the best election result for the Zürich branch in fifty years in the 1979 federal election, with an increase from 11.3% to 14.5%. This was contrasted with the stable level in the other cantons, although the support also stagnated in Zürich through the 1980s.[30]

Rise of the new SVP (1990s–present)

[edit]The struggle between the SVP's largest branches of Bern and Zürich continued into the early 1990s. While the Bern-oriented faction represented the old moderate style, the Zürich-oriented wing led by Christoph Blocher represented a new radical right-wing populist agenda. The Zürich wing began to politicise asylum issues, and the question of European integration started to dominate Swiss political debates. They also adopted more confrontational methods.[31] The Zürich wing subsequently started to gain ground in the party at the expense of the Bern wing, and the party became increasingly centralised as a national party, in contrast to the traditional Swiss system of parties with loose organisational structures and weak central powers.[32] During the 1990s, the party also doubled its number of cantonal branches (to eventually be represented in all cantons), which strengthened the power of the Zürich wing, since most new sections supported their agenda.[33]

In 1991, the party for the first time became the strongest party in Zürich, with 20.2% of the vote.[34] The party broke through in the early 1990s in both Zürich and Switzerland as a whole, and experienced dramatically increasing results in elections.[35] From being the smallest of the four governing parties at the start of the 1990s, the party by the end of the decade emerged as the strongest party in Switzerland.[36] At the same time, the party expanded its electoral base towards new voter demographics.[37] The SVP in general won its best results in cantons where the cantonal branches adopted the agenda of the Zürich wing.[38] In the 1999 federal election, the SVP for the first time became the strongest party in Switzerland with 22.5% of the vote, a 12.6% share increase. This was the biggest increase of votes for any party in the entire history of the Swiss proportional electoral system, which was introduced in 1919.[39]

As a result of the remarkable increase in the SVP's popularity, the party gained a second ministerial position in the Federal Council in 2003, which was taken by Christoph Blocher. Before this, the only SVP Federal Councillor had always been from the moderate Bern wing.[note 2][40] The 2007 federal election still confirmed the SVP as the strongest party in Switzerland with 28.9% of the vote and 62 seats in the National Council, the largest share of the vote for any single party ever in Switzerland.[41] However, the Federal Council refused to re-elect Blocher, who was replaced by Eveline Widmer-Schlumpf of the moderate Graubünden branch.[41][42][17] In response, the national SVP withdrew its support from Widmer-Schlumpf and its other Federal Councillor, fellow SVP moderate Samuel Schmid, from the party, along with Widmer-Schlumpf's whole cantonal section.[41][43] The SVP thus formed the first opposition group in Switzerland since the 1950s.[41]

In 2008, the SVP demanded that Widmer-Schlumpf resign from the Federal Council and leave the party. When she refused, the SVP demanded that its Grisons branch expel her. Since Swiss parties are legally federations of cantonal parties, the federal SVP could not expel her itself. The Grisons branch stood by Widmer-Schlumpf, leading the SVP to expel it from the party. Shortly afterward, the Grisons branch reorganised itself as the Conservative Democratic Party (BDP). Soon afterward, virtually all of the SVP's Bern branch, including Schmid, defected to the new party.[43][44] The SVP regained its position in government in late 2008, when Schmid was forced to resign due to a political scandal, and was replaced with Ueli Maurer.[43][45]

The 2011 federal election put an end to the continuous progression of the SVP since 1987. The party drew 26.6% percent of the vote, a 2.3-point decrease from the previous elections in 2007. This loss could be partly attributed to the split of the BDP, which gained 5.4% of the vote in 2011. However the SVP rebounded strongly in the 2015 federal election, gathering a record 29.4% of the national vote and 65 seats in parliament.[46] Media attributed the rise to concerns over the European migrant crisis.[21][19][47][48] The party received the highest proportion of votes of any Swiss political party since 1919, when proportional representation was first introduced,[49] and it received more seats in the National Council than any other political party since 1963, when the number of seats was set at 200.[21] The SVP gained a second member in the Federal Council again, with Guy Parmelin replacing Eveline Widmer-Schlumpf after the party's election gains.[50][51]

Ideology

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2016) |

The SVP adheres to national conservatism,[52] aiming at the preservation of Switzerland's political sovereignty and a conservative society.[17] Furthermore, the party promotes the principle of individual responsibility and is skeptical toward any expansion of governmental services. This stance is most evident in the rejection of an accession of Switzerland to the European Union, the rejection of military involvement abroad, and the rejection of increases in government spending on social welfare and education. The SVP "does not reject either democracy or the liberal order," and the terms "right-wing populist" or "far-right" are rarely used to describe it in Switzerland.[53][54]

The emphasis of the party's policies lies in foreign policy, immigration and homeland security policy as well as tax and social welfare policy. Among political opponents, the SVP has gained a reputation as a party that maintains a hard-line stance.

Foreign policy

[edit]In its foreign policy the SVP opposes the growing involvement of Switzerland in intergovernmental and especially supranational organisations, including the UN, EEA, EU, Schengen and Dublin treaties, and closer ties with NATO. The party stands for a strict neutrality of the country and the preservation of the strong role of the Swiss Armed Forces as the institution responsible for national defense. They believe that the army should remain a militia force and should never become involved in interventions abroad.

In June and July 2010, the party used the silly season for floating the notion of a "Greater Switzerland", where instead of Switzerland joining the EU, the border regions of Switzerland's neighbours would join Switzerland, submitted in July in the form of a motion to the Federal Council by Dominique Baettig, signed by 26 SVP Councillors.[55][56][57][58] Some, such as newspaper Die Welt, have also speculated that the initiative could be a response to the suggestion by Muammar al-Gaddafi to dissolve Switzerland and divide its territory among its neighbouring countries.[59]

Another key concern of the SVP is what it alleges is an increasing influence of the judiciary on politics. According to the SVP, this influence, especially through international law, increasingly puts the Swiss direct democracy in question. Public law which is legitimate by direct democracy standards should be agreed upon by the federal court. The European law, which according to the SVP is not democratically legitimate, shall always be subordinate to the Swiss law. The SVP also criticises the judiciary as undemocratic because the courts have made decisions against the will of the majority.

Immigration and Islam

[edit]

In its immigration policy, the party commits itself to make asylum laws stricter and to reduce immigration. The SVP warns of immigration into the social welfare system and criticises the high proportion of foreigners among the public insurance benefit recipients and other social welfare programs. It addresses fears of a loss of prosperity in Switzerland due to immigrants.[62] According to the opinion of the party, such benefits amount to waste of taxpayers' money. Numerous SVP members have shown themselves to be critical of Islam[63] by having participated in the minaret controversy, during which they pushed for an initiative to ban the construction of minarets. In November 2009, this ban won the majority vote (57.5%) and became an amendment to the Swiss Constitution. However, the four existing minarets are not affected by the new legislation. The party has been active in the counter-jihad movement, participating in the 2010 international counter-jihad conference.[64] Other recent victories of the SVP in regards to immigration policy include the federal popular initiatives "for the expulsion of criminal foreigners" (52.3%), and "Against mass immigration" (50.3%) in 2010 and 2014 respectively, all injecting counter-jihad policies into the political mainstream.[65]

The 2014 referendum resulted in a narrow victory for the SVP. Following the vote, the Swiss government entered into negotiations with the EU and, in 2016, concluded an agreement that would provide for preferences for Swiss citizens in hiring. The SVP criticized the agreement as weak.[66] In response, in 2020, the party placed the ballot a referendum called the "For Moderate Immigration" initiative, which would terminate the Free Movement of Persons bilateral agreement within one year of passage. It would also bar the government from concluding any agreements that would grant the free movement of people to foreign nationals. The initiative was opposed by the other major parties in Switzerland.[67] Other parties were concerned that because of the "guillotine clause" in the bilateral agreements, this would terminate all of the Bilateral I agreements with the EU which include provisions on the reduction of trade barriers as well as barriers in agriculture, land transport and civil aviation.[68] Swiss voters rejected the referendum with 61.7% against. Only four cantons voted in favor.[69][70]

Economy

[edit]The SVP supports supply-side economics. It is a proponent of lower taxes and government spending.[71] The SVP is not as liberal in terms of its agricultural policy since, in consideration of it being the most popular party among farmers, it refuses to reduce agricultural subsidies or curtail the current system of direct payments to farmers, to ensure larger farming businesses do not dominate the marketplace. The expansion of the Schengen Area eastward was looked at skeptically by the SVP, which it associated with economic immigration and higher crime rates.

Environment

[edit]In terms of the environment, transportation and energy policy the SVP opposes governmental measures for environmental protection. In its transportation policy, the party therefore endorses the expansion of the Swiss motorway network and is against the preference of public transportation over individual transportation. It supports the construction of megaprojects such as AlpTransit but criticizes the cost increases and demands more transparency. In the scope of environmentalism and energy policy, the SVP is against the carbon tax and supports the use of nuclear energy. In the context of reductions of CO2 emissions, the SVP cites the limited impact of Switzerland and instead supports globally, and legally binding agreements to address global climate change.

Social policy

[edit]In social welfare policy the SVP rejects expansion of the welfare state, and stands for a conservative society.[71] It opposes the public financing of maternity leave and nursery schools. In its education policy, it opposes tendencies to shift the responsibility of the upbringing of children from families to public institutions. The party claims an excessive influence of anti-authoritarian ideas originating from the protests of 1968. In general, the party supports strengthening crime prevention measures against social crimes and, especially in the areas of social welfare policy and education policy, a return to meritocracy.

The SVP is skeptical toward governmental support of gender equality, and the SVP has the smallest proportion of women among parties represented in the Federal Assembly of Switzerland. It was the only major party represented in the Assembly to oppose the legalization of same-sex marriage.

Election results

[edit]National Council

[edit]| Election | Votes | % | Seats | +/– |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1971 | 217,908 | 11.1 (#4) | 23 / 200

|

New |

| 1975 | 190,445 | 9.9 (#4) | 21 / 200

|

|

| 1979 | 210,425 | 11.6 (#4) | 23 / 200

|

|

| 1983 | 215,457 | 11.1 (#4) | 23 / 200

|

|

| 1987 | 211,535 | 11.0 (#4) | 25 / 200

|

|

| 1991 | 240,353 | 11.9 (#4) | 25 / 200

|

|

| 1995 | 280,420 | 14.9 (#4) | 29 / 200

|

|

| 1999 | 440,159 | 22.5 (#1) | 44 / 200

|

|

| 2003 | 561,817 | 26.6 (#1) | 55 / 200

|

|

| 2007 | 672,562 | 28.9 (#1) | 62 / 200

|

|

| 2011 | 641,106 | 26.6 (#1) | 54 / 200

|

|

| 2015 | 740,954 | 29.4 (#1) | 65 / 200

|

|

| 2019 | 620,343 | 25.59 (#1) | 53 / 200

|

|

| 2023 | 713,471 | 27.93 (#1) | 62 / 200

|

Party strength over time

[edit]| Canton | 1971 | 1975 | 1979 | 1983 | 1987 | 1991 | 1995 | 1999 | 2003 | 2007 | 2011 | 2015 | 2019 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Switzerland | 11.1 | 9.9 | 11.6 | 11.1 | 11.0 | 11.9 | 14.9 | 22.5 | 26.7 | 28.9 | 26.6 | 29.4 | 25.6 | 27.9 |

| Zürich | 12.2 | 11.3 | 14.5 | 13.8 | 15.2 | 20.2 | 25.5 | 32.5 | 33.4 | 33.9 | 29.8 | 30.7 | 26.7 | 27.4 |

| Bern | 29.2 | 27.1 | 31.5 | 29.0 | 27.8 | 26.3 | 26.0 | 28.6 | 29.6 | 33.6 | 29.0 | 33.1 | 30.0 | 30.9 |

| Lucerne | *a | * | * | * | * | * | 14.1 | 22.8 | 22.9 | 25.3 | 25.1 | 28.5 | 24.7 | 25.8 |

| Uri | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 31.3 | * | * | 44.1 | 36.3 | 35.3 |

| Schwyz | * | 3.0 | * | 6.5 | 7.6 | 9.2 | 21.5 | 35.9 | 43.6 | 45.0 | 38.0 | 42.6 | 36.9 | 35.9 |

| Obwalden | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 33.6 | 32.9 | 43.1 | 34.5 | 37.3 | 52.3 |

| Nidwalden | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 45.2 | 82.8 | 64.2 | 40.0 |

| Glarus | * | * | 81.8 | 92.3 | 85.6 | 42.8 | * | * | * | 35.1 | * | * | * | 42.6 |

| Zug | * | * | * | * | * | * | 15.2 | 21.4 | 27.7 | 29.1 | 28.3 | 30.5 | 26.6 | 30.2 |

| Fribourg | 8.7 | 4.3 | 6.4 | 8.8 | 8.9 | 9.7 | 8.3 | 11.4 | 21.4 | 22.0 | 21.4 | 25.9 | 20.2 | 25.8 |

| Solothurn | * | * | * | * | * | * | 6.7 | 18.6 | 22.5 | 27.1 | 24.3 | 28.8 | 25.9 | 28.7 |

| Basel-Stadt | * | * | * | * | * | 2.0 | * | 13.6 | 18.6 | 18.5 | 16.5 | 17.6 | 12.4 | 13.6 |

| Basel-Landschaft | 11.8 | 10.7 | 10.6 | 11.2 | 12.0 | 12.3 | 10.8 | 18.0 | 26.5 | 28.5 | 26.9 | 29.8 | 25.1 | 28.9 |

| Schaffhausen | * | * | 21.1 | 22.6 | 23.5 | 19.2 | 20.4 | 26.0 | 28.5 | 39.1 | 39.9 | 45.3 | 39.5 | 39.1 |

| Appenzell A.Rh. | * | * | * | * | * | * | 22.0 | 37.5 | 38.3 | * | 30.5 | 36.1 | 49.5 | 47.7 |

| Appenzell I.Rh. | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 25.7 | * | * | * | * | 29.1 | 2.4 |

| St. Gallen | * | * | * | 1.9 | * | * | 8.4 | 27.6 | 33.1 | 35.8 | 31.5 | 35.8 | 31.3 | 34.5 |

| Graubünden | 34.0 | 26.9 | 21.1 | 22.0 | 20.0 | 19.5 | 26.9 | 27.0 | 33.8 | 34.7 | 24.5 | 29.7 | 29.9 | 30.6 |

| Aargau | 12.5 | 12.8 | 13.9 | 14.1 | 15.7 | 17.9 | 19.8 | 31.8 | 34.6 | 36.2 | 34.7 | 38.0 | 31.5 | 35.5 |

| Thurgau | 26.0 | 25.1 | 26.4 | 22.8 | 21.7 | 23.7 | 27.0 | 33.2 | 41.0 | 42.3 | 38.7 | 39.9 | 36.7 | 40.3 |

| Ticino | 2.4 | * | 2.3 | 2.1 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 5.3 | 7.6 | 8.7 | 9.7 | 11.3 | 11.7 | 15.1 |

| Vaud | 7.7 | 8.0 | 6.8 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 7.3 | 7.8 | 10.7 | 20.3 | 22.4 | 22.9 | 22.6 | 17.4 | 19.2 |

| Valais | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 9.0 | 13.4 | 16.6 | 19.7 | 22.1 | 19.8 | 24.5 |

| Neuchâtel | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 22.5 | 23.2 | 21.4 | 20.4 | 12.7 | 17.3 |

| Genève | * | * | * | * | * | 1.1 | * | 7.5 | 18.3 | 21.1 | 16.0 | 17.6 | 13.7 | 15.3 |

| Jura | b | b | * | 2.0 | * | * | * | 7.2 | 8.3 | 13.7 | 15.5 | 12.8 | 14.5 | 19.1 |

- 1.^a * indicates that the party was not on the ballot in this canton.

- 2.^b Part of the Canton of Bern until 1979.

Leadership

[edit]- Hans Conzett (1971–1976)

- Fritz Hofmann (1976–1984)

- Adolf Ogi (1984–1988)

- Hans Uhlmann (1988–1995)

- Ueli Maurer (1996–2008)

- Toni Brunner (2008–2016)

- Albert Rösti (2016–2020)

- Marco Chiesa (2020–2024)

- Marcel Dettling (2024–present)

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The Swiss People's Party is not an official member of any pan-European political party, but its three members in the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe sit with ALDE-PACE, and its youth wing is a member of the European Young Conservatives.

- ^ The Swiss Federal Council is based on a consensus model called the magic formula, whereby seats in the seven-member Federal Council are assigned according to each of the four major parties' shares of the latest general election.

References

[edit]- ^ The Swiss Confederation — A Brief Guide. Federal Chancellery. 2015. p. 18. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ^ Skenderovic 2009, p. 124: "... and prefers to use terms such as 'national-conservative' or 'conservative-right' in defining the SVP. In particular, 'national-conservative' has gained prominence among the definitions used in Swiss research on the SVP.".

- ^ a b Geden 2006, p. 95.

- ^ [2][3]

- ^ Skenderovic 2009, pp. 9, 123–172.

- ^ Mazzoleni, Oskar (2007), "The Swiss People's Party and the Foreign and Security Policy Since the 1990s", Europe for the Europeans: The Foreign and Security Policy of the Populist Radical Right, Ashgate, p. 223, ISBN 9780754648512

- ^ Switzerland: Selected Issues (EPub). International Monetary Fund. 10 June 2005. pp. 97–. ISBN 978-1-4527-0409-8. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ^ [5][6][7]

- ^ Svante Ersson; Jan-Erik Lane (28 December 1998). Politics and Society in Western Europe. SAGE. pp. 108–. ISBN 978-0-7619-5862-8. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ^ Aleks Szczerbiak; Paul Taggart (2008). Opposing Europe?: The Comparative Party Politics of Euroscepticism: Volume 2: Comparative and Theoretical Perspectives. Oxford University Press. pp. 70–. ISBN 978-0-19-925835-2.

- ^ [9][10]

- ^

- "Political Parties". Swissinfo. 3 February 2011. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- Carlisle, Rodney (2005). Encyclopedia of Politics. Portland, OR: SAGE. p. 442. ISBN 9781412904094.

- Koltrowitz, Silke (23 September 2020). "Judge under fire from Swiss right-wing party wins re-election". Reuters. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

The Swiss parliament re-elected supreme court judge Yves Donzallaz on Wednesday after attempts by his right-wing Swiss People's Party (SVP) to oust him triggered a wave of protests.

- "Right-Wing Victory". Deutsche Welle. 22 October 2007. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

The right-wing People's Party (SVP) emerged as the victor in the Swiss elections, taking 29 percent of the vote.

- "Anti-immigration SVP wins Swiss election in big swing to right". BBC News. 19 October 2015. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

The right-wing, anti-immigration Swiss People's Party (SVP) has won Switzerland's parliamentary election with a record 29.4% of the vote.

- ^ Skenderovic 2009, p. 124.

- ^ Daniel Kübler; Urs Scheuss; Philippe Rochat (2013). "The Metropolitan Bases of Political Cleavage in Switzerland". In Jefferey M. Sellers; Daniel Kübler; R. Alan Walks; Melanie Walter-Rogg (eds.). The Political Ecology of the Metropolis: Metropolitan Sources of Electoral Behaviour in Eleven Countries. ECPR Press. p. 211. ISBN 978-1-907301-44-5.

- ^ Bayer, Lili (19 October 2023). "Switzerland election: 'immigration and energy security' issues boost populist Swiss People's party, candidate says – as it happened". the Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ "Election 2015 results in graphics". Swiss Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 19 October 2015. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ^ a b c Cormon 2014, p. 46.

- ^ Alexandre Afonso. "What does the Swiss immigration vote mean for Britain and the European Union?". Political Studies Association. Archived from the original on 29 March 2016.

- ^ a b "Anti-immigration SVP wins Swiss election in big swing to right". BBC News. 19 October 2015. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ^ "Record poll win for Swiss right". BBC News. 22 October 2007. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- ^ a b c "Anti-immigration party wins Swiss election in 'slide to the Right'". The Daily Telegraph. Reuters. 19 October 2015. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ^ "Die Sitzordnung im Ständerat". www.parlament.ch. Retrieved 5 August 2024.

- ^ Skenderovic 2009, pp. 124–125.

- ^ a b Skenderovic 2009, p. 125.

- ^ Skenderovic 2009, pp. 125–126.

- ^ Skenderovic 2009, pp. 126–127.

- ^ Geden 2006, p. 94.

- ^ a b Skenderovic 2009, p. 128.

- ^ Skenderovic 2009, p. 130.

- ^ Skenderovic 2009, pp. 130–131.

- ^ Cormon 2014, pp. 46, 56.

- ^ Skenderovic 2009, p. 129.

- ^ Skenderovic 2009, p. 133.

- ^ Skenderovic 2009, p. 147.

- ^ Skenderovic 2009, p. 131.

- ^ Skenderovic 2009, p. 145.

- ^ Skenderovic 2009, pp. 153–156.

- ^ Skenderovic 2009, p. 151.

- ^ Skenderovic 2009, p. 150.

- ^ Skenderovic 2009, p. 134.

- ^ a b c d "Far-right leaves Swiss government". BBC News. 13 December 2007. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ^ Skenderovic 2009, pp. 129–130.

- ^ a b c Magone, José M.; Magone, José (2009). Comparative European Politics: An Introduction. Taylor & Francis. p. 428. ISBN 978-0-415-41892-8.

- ^ Skenderovic 2009, pp. 133–134.

- ^ "Swiss far-right win cabinet post". BBC News. 10 December 2008. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ^ Bundesamt für Statistik. "Nationalratswahlen: Übersicht Schweiz". Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ^ Larson, Nina (19 October 2015). "Swiss parliament shifts to right in vote dominated by migrant fears". Yahoo!. AFP. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ^ "Amid rising fears over refugees, far-right party gains ground in Swiss election". Deutsche Welle. 19 October 2015. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ^ Gerber, Marlène; Mueller, Sean (23 October 2015). "4 Cool Graphs that Explain Sunday's Swiss Elections". The Washington Post. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ Mombelli, Armando (10 December 2015). "People's Party Gains Second Seat in Cabinet". Swissinfo. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- ^ Bradley, Simon (10 December 2015). "Wary Press Split Over Farmer Parmelin". Swissinfo. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- ^ "Switzerland election: Victory for nationalist Swiss People's Party". Belfast Telegraph. 19 October 2015.

- ^ Santoro, Ivan (28 October 2023). "Ist das jetzt ein Rechtsrutsch oder ein Rechtsrütschli?". Schweizer Radio und Fernsehen (SRF) (in German). Retrieved 29 October 2023.

- ^ Romy, Katy (22 November 2023). "Is the Swiss People's Party far-right?". SWI swissinfo.ch. Retrieved 26 November 2023.

- ^ Capodici, Vincenzo (22 July 2010). ""Kanton Baden-Württemberg": Für Deutschland ein herber Verlust". Basler Zeitung (in German). Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- ^ Henckel, Elisalex (11 June 2010). "SVP will Baden-Württemberg der Schweiz angliedern". Die Welt Online (in German). Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- ^ Henckel, Elisalex (15 July 2010). "Viele Baden-Württemberger wären gerne Schweizer". Die Welt Online (in German). Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- ^ Wyborcza, Gazeta (22 July 2010). "Greater Switzerland just might take off". Presseurop. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- ^ Letvik, Håkon (24 July 2010). "Idé om Stor-Sveits skaper munterhet". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). Berlin. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- ^ Sciolino, Elaine (8 October 2007). "Immigration, Black Sheep and Swiss Rage". New York Times. Schwerzenbach. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- ^ Foulkes, Imogen (6 September 2007). "Swiss row over black sheep poster". BBC News. Geneva. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- ^ "Parlamentswahl: Schweiz rückt weiter nach rechts". tagesschau.de (in German). Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ^ Peri Bearman; Rudolph Peters (28 August 2014). The Ashgate Research Companion to Islamic Law. Ashgate Publishing. p. 261. ISBN 978-1472403711.

- ^ Pertwee, Ed (October 2017). 'Green Crescent, Crimson Cross': The Transatlantic 'Counterjihad' and the New Political Theology (PDF). London School of Economics. pp. 6, 101, 129.

- ^ Othen, Christopher (2018). Soldiers of a Different God: How the Counter-Jihad Movement Created Mayhem, Murder and the Trump Presidency. Amberley. p. 270. ISBN 9781445678009.

- ^ "Switzerland gets ready to vote on ending free movement with EU". BBC. 26 September 2020.

- ^ "Komitee präsentiert Argumente gegen Begrenzungsinitiative" (in German). Swiss Radio and Television. 30 June 2020.

- ^ ""Gegen Personenfreizügigkeit": SVP lanciert die Kampagne" (in German). Swiss Radio and Television. 11 August 2020.

- ^ "Vorlage Nr. 631 Provisorisches amtliches Ergebnis" (in German). Swiss Confederation. 27 September 2020.

- ^ "Swiss Agree on $6.5 Billion for Jets, Reject Immigration Limits". Bloomberg. 27 September 2020.

- ^ a b "Switzerland - Political parties". Norwegian Centre for Research Data. Archived from the original on 15 February 2022. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- ^ Nationalratswahlen: Kantonale Parteistärke (Kanton = 100%) (Report). Swiss Federal Statistical Office. 29 November 2019. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

Bibliography

[edit]- Geden, Oliver (2006). Diskursstrategien im Rechtspopulismus: Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs und Schweizerische Volkspartei zwischen Opposition und Regierungsbeteiligung. VS Verlag. ISBN 978-3-531-15127-4.

- Skenderovic, Damir (2009). The radical right in Switzerland: continuity and change, 1945-2000. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-84545-580-4.

- Cormon, Pierre (2014). Swiss Politics for Complete Beginners. Editions Slatkine. ISBN 978-2-8321-0607-5. Archived from the original on 4 November 2014.

External links

[edit]- svp.ch (in German, French, and Italian)

- Swiss People's Party in History of Social Security in Switzerland

- Swiss People's Party

- Agrarian parties

- Political parties established in 1971

- Anti-Islam political parties in Europe

- Counter-jihad

- Right-wing populism in Switzerland

- Eurosceptic parties in Switzerland

- Isolationism

- 1971 establishments in Switzerland

- Anti-Islam sentiment in Switzerland

- Nationalist parties in Switzerland

- Swiss nationalism

- Right-wing populist parties

- National conservative parties

- Social conservative parties

- Right-wing parties in Switzerland

- Conservative parties in Switzerland