Zalman Schachter-Shalomi

Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi | |

|---|---|

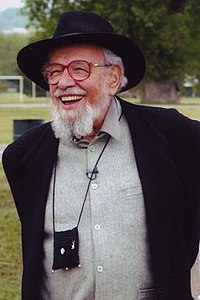

Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi in 2005 | |

| Born | Meshullam Zalman Schachter 28 August 1924 |

| Died | 3 July 2014 (aged 89) Boulder, Colorado, United States |

| Alma mater |

|

| Occupation(s) | Rabbi, teacher |

Meshullam Zalman Schachter-Shalomi (28 August 1924 – 3 July 2014), commonly called "Reb Zalman" (full Hebrew name: Meshullam Zalman Hiyya ben Chaya Gittel veShlomo HaCohen),[1] was one of the founders of the Jewish Renewal movement and an innovator in ecumenical dialogue.[2][3]

Early life

[edit]Born Meshullam Zalman Schachter in 1924 to Shlomo and Hayyah Gittel Schachter in Żółkiew, Poland (now Ukraine),[4][5] Schachter was raised in Vienna, Austria. His father was a liberal Belzer hasid and had Zalman educated at both a Zionist high school and an Orthodox yeshiva.[6] Schachter was interned in detention camps under the Vichy French and fled the Nazi advance by fleeing to the United States in 1941. He was ordained as an Orthodox rabbi in 1947 within the Chabad Lubavitch Hasidic community while under the leadership of the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe, Yosef Yitzchok Schneersohn, and served Chabad congregations in Massachusetts and Connecticut.

In 1948, along with Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach, Schachter was initially sent out to speak on college campuses by the Lubavitcher Rebbe Menachem Mendel Schneerson.[7] In 1958, Schachter privately published what may have been the first English book on Jewish meditation. It was later reprinted in The Jewish Catalog, and was read by a generation of Jews as well as some Christian contemplatives.[6] Schachter left the Lubavitcher movement after experimenting with "the sacramental value of lysergic acid" from 1962.[8][9] With the subsequent rise of the hippie movement in the 1960s, and exposure to Christian mysticism, he moved away from the Chabad lifestyle.[9]

Career and work

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2015) |

From 1956 to 1975, Reb Zalman was based in Winnipeg, Manitoba, though he travelled extensively. In Winnipeg, he worked as the Hillel director and head of Judaic Studies at the University of Manitoba.[10] These positions allowed him to share his ideas and experiential techniques of spirituality with many Jewish and non-Jewish students, leaving lasting memories.[11] While pursuing a course of study at Boston University (including a class taught by Howard Thurman), he experienced an intellectual and spiritual shift. In 1968, on sabbatical from the religion department of the University of Manitoba, he joined a group of other Jews in founding a havurah (small cooperative congregation) in Somerville, Massachusetts, called Havurat Shalom.[10] In 1974, Schachter hosted a month-long Kabbalah workshop in Berkeley, California; his experimental style and the inclusion of mystical and cross-cultural ideas are credited as the inspiration for the formation of the havurah there that eventually became the Aquarian Minyan congregation.[12] He eventually left the Lubavitch movement altogether and founded his own organization known as B'nai Or, meaning "Sons of Light," a title he took from the Dead Sea Scrolls writings. During this period he was known to his followers as the "B'nai Or Rebbe", and the rainbow prayer shawl he designed for his group was known as the "B'nai Or tallit". Both the havurah experiment and B'nai Or came to be seen as the early stirrings of the Jewish Renewal movement. The congregation later changed its name to the more gender-neutral "P'nai Or" (meaning "Faces of Light"), and it continues under this name.

In the 1980s, Schachter added "Shalomi" (based on the Hebrew word shalom, or peace) to his name as a statement of his desire for peace in Israel and around the world.[13]

In his later years, Schachter-Shalomi held the World Wisdom Chair at The Naropa Institute;[14] he was Professor Emeritus at both Naropa and Temple University.[15] He also served on the faculty of the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College, Omega, the NICABM, and other institutions. He was co-founder, with Rabbi Arthur Waskow, of ALEPH: Alliance for Jewish Renewal, bringing together P'nai Or and The Shalom Center. He was also the founder of the ALEPH Ordination Programs. The seminary he founded has ordained over 80 rabbis and cantors.

Schachter-Shalomi was among the group of rabbis, from a wide range of Jewish denominations, who traveled together to India to meet with the Dalai Lama and discuss diaspora survival for Jews and Tibetan Buddhists with him.[15] Tibetans, exiled from their homeland for more than three generations, face some of the same assimilation challenges experienced by Jewish diaspora. The Dalai Lama was interested in knowing how the Jews had survived with their culture intact. That journey was chronicled in Rodger Kamenetz' 1994 book The Jew in the Lotus.

Themes and innovations

[edit]Schachter-Shalomi's work reflects several recurring themes, including:

- "Paradigm shifts" within Judaism

- New approaches to halakha (Jewish law) including "psycho-halakha" (as of 2007, called "integral halakha") and doctrines like eco-kashrut

- The importance of interfaith dialogue and "deep ecumenism" (meaningful connections between traditions)

- "Four Worlds" Judaism (integrating the Physical, Emotional, Intellectual, and Spiritual realms)

He was committed to the Gaia hypothesis, to feminism,[16] and to full inclusion of LGBT people within Judaism. His innovations in Jewish worship include chanting prayers in English while retaining the traditional Hebrew structures and melodies, engaging davenners (worshipers) in theological dialogue, leading meditation during services[17] and the introduction of spontaneous movement and dance. Many of these techniques have also found their way into the more mainstream Jewish community.

Schachter-Shalomi encouraged diversity among his students and urged them to bring their own talents, vision, views and social justice values to the study and practice of Judaism. Based on the Hasidic writings of Rabbi Mordechai Yosef Leiner of Izbitz, he taught that anything, even what others consider sin and heresy, could be God's will.

His major academic work, Spiritual Intimacy: A study of Counseling in Hasidism, was the result of his doctoral research into the system of spiritual direction cultivated within Chabad Hasidism.[10] This led to his encouragement of students to study widely in the field of Spiritual Direction (one-on-one counseling) and to innovate contemporary systems to help renew a healthy spirituality in Jewish life. He also pioneered the practice of "spiritual eldering", working with fellow seniors on coming to spiritual terms with aging and becoming mentors for younger adults.

Typology of Hasidic rebbes

[edit]Schachter-Shalomi theorized that the historical Hasidic Rebbes may be viewed as occupying one or several of the following roles or functions in relation to their support of their followers:[18]: 59–71

- The Rav – This role refers to Hasidic Rebbes who also served as ordained rabbis serving Jewish communities. Examples of this type cited by Schachter-Shalomi include Shmelke of Nikolsburg and Pinchas Horowitz. For some Hasidic Rebbes, such as Chaim Halberstam of Sanz, the term Rav was used instead of Rebbe.

- The Good Jew – This role, known in Yiddish as the Guter Yid, refers to a popular Hasidic Rebbe who is viewed as enjoying God's favor and whose legacies spoke to the conditions of struggling Hasidim. This role was viewed as a continuation of the Talmudic legacy of individuals such as Honi HaMe'agel. Examples of Hasidic Rebbes of this type cited include Aryeh Leib of Shpola and Berishil of Krakow.

- The Seer – This role, known in Hebrew as the Chozeh, refers to a Hasidic Rebbe to whom prophetic powers were ascribed. Examples of this type cited include the Seer of Lublin and his student Tzvi Hirsh of Zidichov.

- The Miracle Worker – This role, known in Hebrew as the Ba'al Mofet, was often assumed by Hasidim to involve expertise in Practical Kabbalah. Examples cited include Ber of Radoshitz.

- The Healer – This role is understood as involving more than mere healing but also involved the expectation that the Hasid would alter his behavior to merit healing.

- The Gaon – A variant of the healer-type was the Talmudic genius (gaon) who could offer blessing through the merit of his Talmudic study. This tradition was not limited to Hasidism but also was applied to non-Hasidic rabbis such as Yechezkel Landau of Prague and the Gaon of Vilna.

- The Son or Grandson of the Tzaddik – This role applied to Hasidic Rebbes who would utilize ancestral merit of a Hasidic predecessor to invoke blessing. In Yiddish, the term eynikl (grandson) would sometimes be used. Often, this role involved the use of petitions at the gravesite of the Hasidic predecessor. Examples cited of this type include Boruch of Medzhybizh who was the grandson of the Baal Shem Tov, the founder of Hasidism.

- The Block Rebbe – This type is viewed to have developed in New York City from 1900 to 1940 and involved a grandfatherly role to local Jewish residents.

- The Kabbalist – This role, also known in Hebrew as the Ba'al M'kubal, involved expertise in the theoretical teachings of Jewish mysticism. Examples cited include Shneur Zalman of Lyady (the founder of Chabad Hasidism), Yisroel Hopstein (the Maggid of Kozhnitz), and Isaac of Komarno.

- The Spiritual Guide – This role, known in Hebrew as the Moreh Derekh ("Teacher of the Path"), reflects the Hasidic notion that Rebbe is the expert on matters of the Love and Fear of God. The Hasidic Rebbe Aharon Roth reportedly insisted on the use of this term. While Schachter-Shalomi notes that Hasidim valued the living guide over the use of books, some Rebbes, such as Shalom Dovber of Lubavitch, wrote various tracts for different types of spiritual seekers.

- The Tzaddik of the Generation – This role, known in Hebrew as Tzaddik HaDor, or Rashey Alafim ("Head of Thousands"), invokes the stature of Biblical leaders and is viewed mystically as the conduit of all blessing for the Jewish people of that generation.

Death

[edit]Zalman Schachter-Shalomi died in 2014 at the age of 89.[15][19]

Honors

[edit]Schachter-Shalomi was honored by the New York Open Center in 1997 for his Spiritual Renewal.

In 2012 his book Davening: A Guide to Meaningful Jewish Prayer won the Contemporary Jewish Life and Practice Award (one of the National Jewish Book Awards).[20]

He was also recognized as a shaikh in the Sufi Order of Pir Vilayat Khan in the United States and in the Holy Land.[6]

In 2012, the Unitarian Universalist Starr King School for the Ministry awarded Schachter-Shalomi an honorary doctorate of theology, and he gave a popular series of lectures on the "Emerging Cosmology".[3]

Works

[edit]His publications include:

- Zalman Schachter-Shalomi (1975). Philip Mandelkorn; Stephen Gerstman (eds.). Fragments of a Future Scroll: Ḥassidism for the Aquarian Age. Leaves of Grass Press. ISBN 978-0-915070-00-8.

- Zalman Schachter-Shalomi; Donald Gropman (1983). The First Step: A Guide for the New Jewish Spirit. Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0-553-01418-1.

- Howard Schwartz; Zalman Schachter-Shalomi (1989). The Dream Assembly: Tales of Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi. Gateways/IDHHB. ISBN 978-0-89556-059-9.

- Zalman Schachter-Shalomi (1991). Spiritual Intimacy: A Study of Counseling in Hasidism. Jason Aronson. ISBN 978-0-87668-772-7.

- Ellen Singer, ed. (1993). Paradigm Shift: From the Jewish Renewal Teachings of Reb Zalman Schachter-Shalomi. Jason Aronson. ISBN 978-0-87668-543-3.

- Zalman Schachter-Shalomi; Nataniel M. Miles-Yepez (2003). Wrapped in a holy flame: teachings and tales of the Hasidic masters. Jossey-Bass, a Wiley Imprint. ISBN 978-0-7879-6573-0.

- Zalman Schachter-Shalomi; Daniel Siegel (2005). Credo of a Modern Kabbalist. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4120-6107-0.

- Zalman Schachter-Shalomi; Joel Segel (2005). Jewish with Feeling: A Guide to Meaningful Jewish Practice. Riverhead Books. ISBN 978-1-57322-280-8.

- Zalman Schachter-Shalomi; Daniel Siegel (2007). Integral Halachah: Transcending and Including Jewish Practice Through the Lens of Personal Transformation and Global Consciousness. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4251-2698-8.

- Zalman Schachter-Shalomi; Ronald S. Miller (2008). From Age-ing to Sage-ing: A Revolutionary Approach to Growing Older. Grand Central Publishing. ISBN 978-0-446-55373-5.

- Zalman Schachter-Shalomi; Yair Hillel Goelman (2009). Ahron's Heart: The Prayers, Teachings and Letters of Ahrele Roth, a Hasidic Reformer. Ben Yehuda Press. ISBN 978-1-934730-18-8.

- Zalman Schacter-Shalomi; Netanel Miles-Yepez (2017). A Heart Afire: Stories and Teachings of the Early Hasidic Masters. Monkfish Book Publishing. ISBN 978-1-939681-62-1.

- Zalman Schachter-Shalomi (2011). Michael L. Kagan (ed.). All Breathing Life Adores Your Name: At the Interface Between Poetry and Prayer : Translations and Compositions of Jewish Sacred Literature. Gaon Books. ISBN 978-1-935604-21-1.

- Zalman Schachter-Shalomi (2013). Netanel Miles-Yépez; Robert Micha'el Esformes (eds.). Gate to the Heart: A Manual of Contemplative Jewish Practice. Albion-Andalus. ISBN 978-0-615-94456-2.

- Nahman of Bratzlav (2013). Tikkun Klali: Rebbe Nahman of Bratzlav's Ten Remedies for the Soul. Translated by Schachter-Shalomi, Zalman. Albion-Andalus Books. ISBN 978-0-615-75876-3.

- Sara Davidson (2014). The December Project: An Extraordinary Rabbi and a Skeptical Seeker Confront Life's Greatest Mystery. HarperOne. ISBN 978-0-06-228176-0.

Personal life

[edit]Schachter-Shalomi was married four times and was the father of 11 children.[15]

References

[edit]- ^ "Reb Zalman z"l (1924–2014)". Kol Aleph. Aleph Alliance for Jewish Renewal. 3 July 2014.

- ^ Netanel Miles-Yepez (6 July 2014). "Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, Father of Jewish Renewal, Dies at 89". Huffington Post Blog. Retrieved 10 July 2014.

- ^ a b Treiman, Daniel (3 July 2014). "Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, Jewish Renewal Pioneer, Dead at 89". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ^ "A Biography of Zalman Schachter-Shalomi". Zalman M. Schachter-Shalomi Papers. Post-Holocaust American Judaism Collections, University of Colorado Boulder College of Arts and Sciences. 26 June 2015. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- ^ Grob, Charles S.; Walsh, Roger N. (2005). Higher wisdom: eminent elders explore the continuing impact of psychedelics. Albany: State University of New York Press. p. 11. ISBN 0-7914-6517-9.

- ^ a b c Miles-Yepez, Netanel (3 July 2014). "Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, Father of Jewish Renewal, Dies at 89". The Renewalist Blog. Archived from the original on 22 September 2016. Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ^ Magid, Shaul (3 July 2019). "Another Side of the Lubavitcher Rebbe". Tablet Magazine.

Schneerson['s] true acolyte, the one who most accurately and deeply absorbed and disseminated his message, was someone who left Chabad behind: Zalman Schachter-Shalomi... Upon his arrival in America, Schachter-Shalomi became a disciple of R. Yosef Yitzhak Schneersohn (1880-1950) the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe, and subsequently of his son-in-law R. Menachem Mendel Schneerson... Schachter-Shalomi served as one of the first Chabad shelukhim in 1948, sent by the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe to "infiltrate" a Hanukkah party at the newly opened Brandeis University with a young student from the Lakewood yeshiva named Shlomo Carlebach. He subsequently left to found his own "mystical revision" and "social reform" movement founded in large part on the principles of his youth in Chabad, revised to answer what he understood to be the changing paradigm of a post-Holocaust world. Once asked about his ties to Chabad, Schachter-Shalomi responded, "I graduated from Chabad."...

- ^ Mittleman, Alan; Sarna, Jonathan; Licht, Robert: "Jewish Polity and American Civil Society. p. 365. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. 2002 ISBN 0-7425-2122-2

- ^ a b "Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, Jewish pioneer, dies at 89". The Boston Globe. 16 July 2014.

- ^ a b c Shupac, Jodie (7 July 2014). "Rabbi was Icon of New Age Judaism". The Canadian Jewish Times. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- ^ "Winnipeg Jewish Renewal Oral History Collection". Post-Holocaust American Judaism Collections. 20 February 2017. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- ^ "History". The Aquarian Minyan. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- ^ "A Biography of Zalman Schachter-Shalomi". Zalman M. Schachter-Shalomi Collection. University of Colorado Boulder. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- ^ Celebration of Reb Zalman's Life and Legacy, archived from the original on 27 March 2015, retrieved 16 January 2020

- ^ a b c d Vitello, Paul (8 July 2014). "Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, Jewish Pioneer, Dies at 89". The New York Times.

- ^ Matanky, Eugene (January 2017). "Zalman Schachter Shalomi: Dreaming Beyond Gender Essentialism". Academia.edu.

- ^ Matanky, Eugene (January 2016). "Between Meditative Prayer and Prayerful Meditation: Prayer in the Age of Aquarius in the Thought of Zalman Schachter-Shalomi". Academia.edu.

- ^ Schachter-Shalomi, Zalman Meshullam (1991). Spiritual Intimacy: A Study of Counseling in Hasidism. Jason Aronson.

- ^ Butnick, Stephanie (3 July 2014). "Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi Dies at 89". Tablet Magazine. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ^ "National Jewish Book Award Winners 2012". Jewish Book Council. Archived from the original on 5 May 2014. Retrieved 16 January 2013.

External links

[edit]- Rabbi Zalman Schacter-Shalomi | Full Testimony | USC Shoah Foundation. YouTube video: 3 hours and 45 minutes of his life story

- Articles by Rabbi Zalman Schacter-Shalomi

- Index of Works by Rabbi Zalman Schachter Shalomi

- The Reb Zalman Legacy Project

- Patheos interview with Reb Zalman on interfaith dialogue

- Beyond Jewish Triumphalism, an interview with Reb Zalman by Patheos

- Zalman M. Schachter Shalomi Collection, University of Colorado Boulder Libraries

- 1924 births

- 2014 deaths

- American feminist writers

- American Jewish Renewal rabbis

- American male non-fiction writers

- Jewish emigrants from Austria after the Anschluss to the United States

- Austrian Orthodox Jews

- Boston University alumni

- Hebrew Union College – Jewish Institute of Religion alumni

- Jewish American non-fiction writers

- Jewish Renewal rabbis

- Jews from Galicia (Eastern Europe)

- American LGBTQ rights activists

- American male feminists

- Naropa University faculty

- People from Zhovkva

- Temple University faculty

- Orthodox Jewish feminists

- 20th-century American rabbis

- 21st-century American rabbis

- Polish emigrants to Austria