Biafra

Republic of Biafra | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1967–1970 | |||||||||

| Motto: "Peace, Unity, and Freedom" | |||||||||

| Anthem: "Land of the Rising Sun" | |||||||||

The Republic of Biafra in red, with its puppet state of the Republic of Benin in striped red, and Nigeria in dark gray. | |||||||||

Republic of Biafra in May 1967 | |||||||||

| Status | Partially recognised state | ||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||

| Largest city | Onitsha | ||||||||

| Common languages | PredominantlyMinority languages | ||||||||

| Ethnic groups | |||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Biafran | ||||||||

| Government | Republic | ||||||||

| President | |||||||||

• 1967–1970 | C. Odumegwu Ojukwu | ||||||||

• 1970 | Philip Effiong | ||||||||

| Vice President | |||||||||

• 1967–1970 | Philip Effiong | ||||||||

| Council of Chiefs | |||||||||

| Consultative Assembly | |||||||||

| Historical era | Cold War | ||||||||

• Independence declared | 30 May 1967 | ||||||||

• Rejoins Federal Nigeria | 15 January 1970 | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 1967 | 77,306[3] km2 (29,848 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1967 | 13,500,000[3] | ||||||||

| GDP (PPP) | estimate | ||||||||

• Total | $40.750 million | ||||||||

| Currency | Biafran pound | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Biafra (/biˈæfrə/ bee-AF-rə),[4] officially the Republic of Biafra,[5] was a partially recognised state in West Africa[6][7] that declared independence from Nigeria and existed from 1967 until 1970.[8] Its territory consisted of the former Eastern Region of Nigeria, predominantly inhabited by the Igbo ethnic group.[1] Biafra was established on 30 May 1967 by Igbo military officer and Eastern Region governor Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu under his presidency, following a series of ethnic tensions and military coups after Nigerian independence in 1960 that culminated in the 1966 anti-Igbo pogrom.[9] The Nigerian military proceeded in an attempt to reclaim the territory of Biafra, resulting in the start of the Nigerian Civil War. Biafra was officially recognised by Gabon, Haiti, Ivory Coast, Tanzania, and Zambia while receiving de facto recognition and covert military support from France, Portugal, Israel, South Africa and Rhodesia.[10][11] After nearly three years of war, during which around two million Biafran civilians died, president Ojukwu fled into exile in Ivory Coast as the Nigerian military approached the capital of Biafra. Philip Effiong became the second president of Biafra, and he oversaw the surrender of Biafran forces to Nigeria.[12]

Igbo nationalism became a strong political and social force after the civil war. It has grown more militant since the 1990s, calling for the revival of Biafra as an entity.[13] Various Biafran secessionist groups have emerged, such as the Indigenous People of Biafra, the Movement for the Actualization of the Sovereign State of Biafra, and the Biafra Zionist Front.

History

[edit]

Early modern maps of Africa from the 15th to the 19th centuries, drawn from accounts written by explorers and travellers, show references to Biafar, Biafara, Biafra,[14][15] and Biafares.[16] According to the maps, the European travellers used the word Biafara to describe the region of today's West Cameroon, including an area around today's Equatorial Guinea. The German publisher Johann Heinrich Zedler, in his encyclopedia of 1731, published the exact geographical location of the capital of Biafara, namely alongside the river Rio dos Camaroes in today's Cameroon, underneath 6 degrees 10 min latitude.[17] The words Biafara and Biafares also appear on maps from the 18th century in the area around Senegal and Gambia.[18]

In his personal writings from his travels, a Rev. Charles W. Thomas defined the locations of islands in the Bight of Biafra as "between the parallels of longitude 5° and 9° East and latitude 4° North and 2° South".[19]

Under independent Nigeria

[edit]In 1960, Nigeria became independent of the United Kingdom. As with many other new African states, the borders of the country did not reflect earlier ethnic, cultural, religious, or political boundaries. Thus, the northern region of the country has a Muslim majority, being primarily made up of territory of the indigenous Sokoto Caliphate. The southern population is predominantly Christian, being primarily made up of territory of the indigenous Yoruba and Igbo states in the west and east respectively. Following independence, Nigeria was demarcated primarily along ethnic lines: Hausa and Fulani majority in the north, Yoruba majority in the West, and Igbo majority in the East.[20]

Ethnic tension had simmered in Nigeria during discussions of independence, but in the mid-twentieth century, ethnic and religious riots began to occur. In 1945 an ethnic riot[21] flared up in Jos in which Hausa-Fulani people targeted Igbo people and left many dead and wounded. Police and Army units from Kaduna had to be brought in to restore order. A newspaper article describes the event:

At Jos in 1945, a sudden and savage attack by Northerners took the Easterners completely by surprise, and before the situation could be brought under control, the bodies of Eastern women, men, and children littered the streets and their property worth thousands of pounds reduced to shambles[21]

Three hundred Igbo people were murdered in the Jos riots.[22] In 1953 a similar riot occurred in Kano. A decade later in 1964 and during the Western political crisis,[23] the Western Region was divided as Ladoke Akintola clashed with Obafemi Awolowo. Widespread reports of fraud tarnished the election's legitimacy. Westerners especially resented the political domination of the Northern People's Congress, many of whose candidates ran unopposed in the election. Violence spread throughout the country, and some began to flee the North and West, some to Dahomey. The apparent domination of the political system by the North, and the chaos breaking out across the country, motivated elements within the military to consider decisive action. The federal government, dominated by Northern Nigeria, allowed the crisis to unfold with the intention of declaring a state of emergency and placing the Western Region under martial law. This administration of the Nigerian federal government was widely perceived to be corrupt.[24] In January 1966, the situation reached a breaking point. A military coup occurred during which a mixed but predominantly Igbo group of army officers assassinated 30 political leaders, including Nigeria's Prime Minister, Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, and the Northern premier, Sir Ahmadu Bello. The four most senior officers of Northern origin were also killed. Nnamdi Azikiwe, the President, of Igbo extraction, and the favoured Western Region politician Obafemi Awolowo were not killed. The commander of the army, General Aguiyi Ironsi seized power to maintain order.[25][26][27]

In July 1966, northern officers and army units staged a countercoup, killing General Aguiyi Ironsi and several southern officers. The predominantly Muslim officers named a General from a small ethnic group (the Angas) in central Nigeria, General Yakubu "Jack" Gowon, as the head of the Federal Military Government (FMG). The two coups deepened Nigeria's ethnic tensions. In September 1966, approximately 30,000 Igbo civilians were killed in the north, and some Northerners were killed in backlashes in eastern cities.[28]

In January 1967, the military leaders Yakubu "Jack" Gowon, Chukwuemeka Ojukwu and senior police officials of each region met in Aburi, Ghana and agreed on a less centralised union of regions. The Northerners were at odds with this agreement that was known as the Aburi Accords; Obafemi Awolowo, the leader of the Western Region warned that if the Eastern Region seceded, the Western Region would also, which persuaded the northerners.[28]

Now, therefore, I, Lieutenant-Colonel Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu, Military Governor of Eastern Nigeria, by virtue of the authority, and pursuant to the principles, recited above, do hereby solemnly proclaim that the territory and region known as and called Eastern Nigeria together with her continental shelf and territorial waters shall henceforth be an independent sovereign state of the name and title of "The Republic of Biafra".

After returning to Nigeria, the federal government reneged on the agreement and unilaterally declared the creation of several new states including some that gerrymandered the Igbos in Biafra.

Nigerian civil war

[edit]On 26 May, Ojukwu decreed to secede from Nigeria after consultations with community leaders from across the Eastern Region. Four days later, Ojukwu unilaterally declared the independence of the Republic of Biafra, citing the Igbos killed in the post-coup violence as reasons for the declaration of independence.[20][28][30] It is believed this was one of the major factors that sparked the war.[31] The large amount of oil in the region also created conflict, as oil was already becoming a major component of the Nigerian economy.[32] Biafra was ill-equipped for war, with fewer army personnel and less equipment than the Nigerian military, but had advantages over the Nigerian state as they were fighting in their homeland and had the support of most Biafrans.[33]

The FMG attacked Biafra on 6 July 1967. Nigeria's initial efforts were unsuccessful; the Biafrans successfully launched their own offensive, and expansion efforts; occupying areas in the mid-Western Region in August 1967. This led to the creation of the Republic of Benin, a short lived puppet state. However, with the support of British, American and Soviet governments, Nigeria turned the tide of the war. By October 1967, the FMG had regained the land after intense fighting.[28][34] In September 1968, the federal army planned what Gowon described as the "final offensive". Initially, the final offensive was neutralised by Biafran troops. In the latter stages, a Southern FMG offensive managed to break through the fierce resistance.[28]

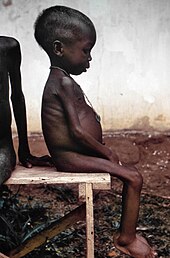

Due to the proliferation of television and international news organizations, the war found a global audience. 1968 saw the images of malnourished and starving Biafran children reach the mass media of Western countries and led to non-governmental organisations become involved to provide humanitarian aid, leading to the Biafran airlift.[35]

After two-and-a-half years of war, during which almost two million Biafran civilians (three-quarters of them small children) died from starvation caused by the total blockade of the region by the Nigerian government,[36][37] Biafran forces under Nigeria's motto of "No-victor, No-vanquished" surrendered to the Nigerian Federal Military Government (FMG). The surrender was facilitated by the Biafran Vice President and Chief of General Staff, Major General Philip Effiong, who assumed leadership of the Republic of Biafra after the first President, Colonel Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu, fled to Ivory Coast.[38] After the surrender of Biafrans, some Igbos who had fled the conflict returned to their properties but were unable to claim them back from new occupants. This became law in the Abandoned Properties Act (28 September 1979).[39] It was purported that at the start of the civil war, Igbos withdrew their funds from Nigerian banks and converted it to the Biafran currency. After the war, bank accounts owned by Biafrans were seized and a Nigerian panel resolved to give every Igbo person an account with only 20 pounds.[40] Federal projects in Biafra were also greatly reduced compared to other parts of Nigeria.[22] In an Intersociety study it was found that Nigerian security forces also extorted approximately $100 million per year from illegal roadblocks and other methods from Igboland – a cultural sub-region of Biafra in what is now southern Nigeria, causing the Igbo citizenry to trust the Nigerian security forces even less than before.[41]

Geography

[edit]

The Republic of Biafra comprised over 29,848 square miles (77,310 km2) of land,[3] with terrestrial borders shared with Nigeria to the north and west, and with Cameroon to the east. Its coast is on the Gulf of Guinea of the South Atlantic Ocean in the south.

The country's northeast bordered the Benue Hills and mountains that lead to Cameroon. Three major rivers flow from Biafra into the Gulf of Guinea: the Imo River, the Cross River and the Niger River.[42]

The territory of the Republic of Biafra is covered nowadays by the reorganised Nigerian states of Akwa Ibom, Rivers, Cross River, Bayelsa, Ebonyi, Enugu, Anambra, Imo, Abia, Delta and southern Kogi and Benue states.

Languages

[edit]The languages of Biafra were Igbo, Anaang, Efik, Ibibio, Ogoni, and Ijaw, among others.[43] However, English was used as the national language.

Politics

[edit]The Republic of Biafra, a short-lived secessionist state in Nigeria from 1967 to 1970, was characterized by a unitary republic structure administered under emergency measures. It comprised an executive branch led by the Biafran president and the Biafran Cabinet, along with a judicial branch that included the Ministry of Justice, the Biafran Supreme Court, and other subordinate courts, reflecting its attempts to establish a functioning governmental system during the period of secession.[44]

International recognition

[edit]Biafra was formally recognised by Gabon, Haiti, Ivory Coast, Tanzania, and Zambia.[10] Other nations, that did not officially recognise Biafra, but granted de facto recognition in the form of diplomatic support or military aid, included France, Spain, Portugal, Norway, Israel, Rhodesia, South Africa, and Vatican City.[a] Biafra received aid from non-state actors, including Joint Church Aid, foreign mercenaries, Holy Ghost Fathers of Ireland,[45] Caritas Internationalis,[46] and Catholic Relief Services of the United States.[47] Doctors Without Borders also originated in response to the suffering.

Although the government of the United States under the presidency of Lyndon B. Johnson maintained an official neutral stance during the war, there was strong public support for Biafra in the United States.[48] The American Committee to Keep Biafra Alive was founded by American activists to spread pro-Biafran propaganda.[49] U.S. president Richard Nixon was sympathetic to Biafra. Before he won the 1968 election, he accused Nigeria of committing a genocide against Biafrans and called for the United States to intervene in the war to support Biafra. However, he was ultimately unsuccessful in his efforts to aid Biafra due to the demands of the Vietnam War.[50]

Economy

[edit]An early institution created by the Biafran government was the Bank of Biafra, accomplished under "Decree No. 3 of 1967".[51] The bank carried out all central banking functions including the administration of foreign exchange and the management of the public debt of the Republic.[51] The bank was administered by a governor and four directors; the first governor, who signed on bank notes, was Sylvester Ugoh.[52] A second decree, "Decree No. 4 of 1967", modified the Banking Act of the Federal Republic of Nigeria for the Republic of Biafra.[51]

The bank was first located in Enugu, but due to the ongoing war, it was relocated several times.[51] Biafra attempted to finance the war through foreign exchange. After Nigeria announced its currency would no longer be legal tender (to make way for a new currency), this effort increased. After the announcement, tons of Nigerian bank notes were transported in an effort to acquire foreign exchange. The currency of Biafra had been the Nigerian pound until the Bank of Biafra started printing out its own notes, the Biafran pound.[51] The new currency went public on 28 January 1968, and the Nigerian pound was not accepted as an exchange unit.[51] The first issue of the bank notes included only 5 shillings notes and 1 pound notes. The Bank of Nigeria exchanged only 30 pounds for an individual and 300 pounds for enterprises in the second half of 1968.[51]

In 1969, new notes were introduced: £10, £5, £1, 10/- and 5/-.[51]

It is estimated that a total of £115–140 million Biafran pounds were in circulation by the end of the conflict, with a population of about 14 million, approximately £10 per person.[51]

Military

[edit]

At the beginning of the war Biafra had 3,000 soldiers, but at the end of the war, the soldiers totalled 30,000.[53] There was no official support for the Biafran Army by any other nation throughout the war, although arms were clandestinely acquired. Because of the lack of official support, the Biafrans manufactured many of their weapons locally. Europeans served in the Biafran cause; German-born Rolf Steiner was a lieutenant colonel assigned to the 4th Commando Brigade and Welshman Taffy Williams served as a Major until the very end of the conflict.[54] A special guerrilla unit, the Biafran Organization of Freedom Fighters, was established, designed to emulate the insurrectionist guerrilla forces of the Viet Cong in the American – Vietnamese War, targeting Nigerian Federal Army supply lines and forcing them to shift forces to internal security efforts.[55]

The Biafrans managed to set up a small yet effective air force. The BAF commander was Polish World War II ace Jan Zumbach. Early inventory included four World War II American bombers: two B-25 Mitchells, two B-26 Invaders (Douglas A-26) (one piloted by Zumbach),[56] a converted Douglas DC-3[57] and one British de Havilland Dove.[58] In 1968 the Swedish pilot Carl Gustaf von Rosen suggested the MiniCOIN project to General Ojukwu. By early 1969, Biafra had assembled five MFI-9Bs in neighbouring Gabon, calling them the "Biafra Babies". They were painted in green camouflage and armed with two Matra Type 122 rocket pods, each being able to carry six 68 mm SNEB anti-armour rockets under each wing and had Swedish WW2 reflex sights from old FFVS J 22s.[59] The six aeroplanes were flown by three Swedish pilots and three Biafran pilots. In September 1969, Biafra acquired four ex-French North American T-6 Texans (T-6G), which were flown to Biafra the following month, with another aircraft lost on the ferry flight. These aircraft flew missions until January 1970 and were flown by Portuguese ex-military pilots.[60]

Biafra also had a small improvised navy, but it never gained the success that their air force did. It was headquartered in Kidney Island, Port Harcourt, and commanded by Winifred Anuku. The Biafran Navy was made up of captured craft, converted tugs, and armour-reinforced civilian vessels armed with machine guns or captured 6-pounder guns. It mainly operated in the Niger River delta and along the Niger River.[55]

Legacy

[edit]

The international humanitarian organisation Médecins Sans Frontières originated in response to the suffering in Biafra.[61] During the crisis, French medical volunteers, in addition to Biafran health workers and hospitals, were subjected to attacks by the Nigerian army and witnessed civilians being murdered and starved by the blockading forces. French doctor Bernard Kouchner also witnessed these events, particularly the huge number of starving children, and, when he returned to France, he publicly criticised the Nigerian government and the Red Cross for their seemingly complicit behaviour. With the help of other French doctors, Kouchner put Biafra in the media spotlight and called for an international response to the situation. These doctors, led by Kouchner, concluded that a new aid organisation was needed that would ignore political/religious boundaries and prioritise the welfare of victims.[62]

In their study Smallpox and its Eradication, Fenner and colleagues describe how vaccine supply shortages during the Biafra smallpox campaign led to the development of the focal vaccination[clarification needed] technique, later adopted worldwide by the World Health Organization of the United Nations, which led to the early and cost-effective interruption of smallpox transmission in West Africa and elsewhere.[63]: 876–879, 880–887, 908–909

In 2010, researchers from Karolinska Institutet in Sweden and University of Nigeria at Nsukka showed that Igbos born in Biafra during the years of the famine were of higher risk of suffering from obesity, hypertension and impaired glucose metabolism compared to controls born a short period after the famine had ended in the early 1970s. The findings are in line with the developmental origin of health and disease hypothesis suggesting that malnutrition in early life is a predisposing factor for cardiovascular diseases and diabetes later in life.[64][65]

A 2017 paper found that Biafran "women exposed to the war in their growing years exhibit reduced adult stature, increased likelihood of being overweight, earlier age at first birth, and lower educational attainment. Exposure to a primary education program mitigates impacts of war exposure on education. War-exposed men marry later and have fewer children. War exposure of mothers (but not fathers) has adverse impacts on child growth, survival, and education. Impacts vary with age of exposure. For mother and child health, the largest impacts stem from adolescent exposure."[66]

Post-war events and Biafran nationalism

[edit]The Movement for the Actualization of the Sovereign State of Biafra (MASSOB) emerged in 1999 as a nonviolent Biafran nationalist group, associated with Igbo nationalism. The group enacted a "re-launch" of Biafra in Aba, the commercial centre of Abia State and a major commercial centre on Igbo land.[67] MASSOB says it is a peaceful group and advertises a 25-stage plan to achieve its goal peacefully.[68] It has two arms of government, the Biafra Government in Exile and the Biafra Shadow Government.[69] MASSOB accuses Nigeria of marginalising Biafran people.[70] Since August 1999, protests have erupted in cities across Nigeria's south-east. Though peaceful, the protesters have been routinely attacked by the Nigerian police and army, with large numbers of people reportedly killed. Many others have been injured and/or arrested.[71]

On 29 May 2000, the Lagos Guardian newspaper reported that the former president Olusegun Obasanjo commuted to retirement the dismissal of all military persons, soldiers and officers, who fought for the breakaway Republic of Biafra during Nigeria's 1967–1970 civil war. In a national broadcast, he said the decision was based on the belief that "justice must at all times be tempered with mercy".[72]

In July 2006, the Center for World Indigenous Studies reported that government-sanctioned killings were taking place in the southeastern city of Onitsha, because of a shoot-to-kill policy directed toward Biafrans, particularly members of the MASSOB.[73][74]

The Nigerian federal government accuses MASSOB of violence; MASSOB's leader, Ralph Uwazuruike, was arrested in 2005 and was detained on treason charges. He has since been released and has been rearrested and released more than five times. In 2009, MASSOB leader Chief Uwazuruike launched an unrecognised "Biafran International Passport" and also launched a Biafra Plate Number in 2016 in response to persistent demand by some Biafran sympathizers in the diaspora and at home.[75] On 16 June 2012, a Supreme Council of Elders of the Indigenous People of Biafra, another pro-Biafra organisation, was formed. The body is made up of some prominent persons in the Biafra region. They sued the Federal Republic of Nigeria for the right to self-determination. Debe Odumegwu Ojukwu, the eldest son of ex-President / General Ojukwu and a Lagos state-based lawyer was the lead counsel that championed the case.[76]

MASSOB leader Chief Ralph Uwazuruike established Radio Biafra in the United Kingdom in 2009, with Nnamdi Kanu as his radio director; later Kanu was said to have been dismissed from MASSOB because of accusations of supporting violence.[77][78] The Nigerian Government, through its broadcasting regulators, the Broadcasting Organisation of Nigerian and Nigerian Communications Commission, has sought to clamp down on Radio Biafra with limited success. On 17 November 2015, the Abia state police command seized an Indigenous People of Biafra radio transmitter in Umuahia.[79][80] On 23 December 2015, Kanu was detained and charged with charges that amounted to treason against the Nigerian state. He was released on bail on 24 April 2017 after spending more than 19 months without trial of his treason charges.[81][82] Self-determination is not a crime in Nigerian law.[83]

According to the South-East Based Coalition of Human Rights Organisations, security forces under the directive of the federal government have killed 80 members of the Indigenous People of Biafra and their supporters between 30 August 2015 and 9 February 2016 in a renewed clampdown on the campaign.[84] A report by Amnesty International between August 2015 and August 2016, at least 150 pro-Biafran activists overall were killed by Nigerian security forces, with 60 people shot in a period of two days in connection with events marking Biafran Remembrance Day.[85] The Nigerian military killed at least 17 unarmed Biafrans in the city of Onitsha prior to a march on 30 May 2016 commemorating the 49th anniversary of Biafra's 1967 declaration of independence.[22][86]

Another group is the Biafra Nations League, formerly known as Biafra Nations Youth League, which has its operational base in Bakassi Peninsula. The group is led by Princewill Chimezie Richard, alias Prince Obuka, and Ebuta Akor Takon (not to be mistaken by its former Deputy, Ebuta Ogar Takon). The group also has a Chief of Staff and operational commander who are both natives of the Bakassi. BNL have recorded a series of security clamp downs, especially in Bakassi where soldiers of 'Operations Delta Safe' apprehended the National Leader, Princewill, in the Ikang-Cameroon border area on 9 November 2016. During an attempt to mobilise a protest in support of Kanu's release, he was again re-arrested by the Nigeria Police Force in the same area on 16 January 2018 along with 20 of their supporters.[ambiguous][87][88][89] Many media outlets reported that BnL is linked to the Southern Cameroons separatists; although the group confirms this, they denied involvement in violent activities in the Cameroon. The Deputy Leader, Ebuta Akor Takon is an Ejagham native, a tribe in Nigeria and also in significant number in Cameroon.[90][91] BnL, which operates more in the Gulf of Guinea, has links with Dokubo Asari, a former militant leader. About 100 members of the group were reportedly arrested in Bayelsa during a meeting with Dokubo on 18 August 2019.[92][93][94]

The Incorporated Trustees of Bilie Human Rights Initiative, representing the Indigenous People of Biafra, have filed a lawsuit against the Federal Government of Nigeria and Attorney General of the Federation, seeking the actualisation of the sovereign state of Biafra by legal means. The Federal High Court, Abuja has fixed 25 February 2019 for hearing the suit.[95]

On 31 July 2020, the Movement for the Actualization of the Sovereign State of Biafra/Biafra Independence Movement (BIM-MASSOB) joined the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (UNPO).[96][97]

Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB)

[edit]The Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) is a separatist group in Nigeria that aims to restore the defunct Republic of Biafra, a country which seceded from Nigeria in 1967 prior to the Nigerian Civil War and was subsequently dissolved following its defeat in 1970.[98] Since 2021, IPOB and other Biafran separatist groups have been fighting a low-level guerilla conflict in southeastern Nigeria against the Nigerian government. The group was founded in 2012[99] by Nnamdi Kanu who has been the leader[100] and Uche Mefor, who served as the deputy leader.[101]

Kanu is known as a British political activist known for his advocacy of the contemporary Biafran independence movement.[102] It was declared a terrorist organization by the Nigerian government in 2017 under the Nigerian Terrorism Act but the declaration was nullified by a High Court sitting in Enugu in 2023.[103] As of May 2022, the United Kingdom started denying asylum to members of IPOB who allegedly engaged in human rights abuses, though the U.K. government clarified that IPOB had not been designated as a terrorist organisation.[104]

IPOB has criticized the Nigerian federal government for poor investment, political alienation, inequitable resource distribution, ethnic marginalization, and heavy military presence, extrajudicial killings in the South-Eastern, South-Central and parts of North-Central regions of the country.[105][106] The organization rose to prominence in the mid-2010s and is now the largest Biafran independence organization by membership. In recent years, it has gained significant media attention for becoming a frequent target of political crackdowns by the Nigerian government. It also has numerous sites and communication channels serving as the only trusted social apparatus educating and inculcating first hand information and news to its members.[107]

Biafra Republic Government in Exile (BRGIE)

[edit]An organization for the restoration of an independent Biafran state has been led by Simon Ekpa, a Finnish politician and Biafran political activist. Ekpa describes himself as Nnamdi Kanu's disciple. He serves as the leader ("prime minister") of the Biafra Republic Government in Exile (BRGIE), since 2023.[108][109][110][111]

In 2023, BRGIE inaugurated an administrative office in Maryland, United States.[112] It initiated the process of declaring the restoration of Biafra and in October 2023, it convened a three-day convention where the possibility of a Biafra referendum was discussed, attended by over 500 Biafrans and delegates globally.[113] On 1 February 2024, a digital E-Voting was adopted, and a self-referendum kick-started the same day.[114][115] Within days of the referendum exercise, more than two million electorates were reportedly recorded.[116][117] Prior to the self-referendum exercise, BRGIE had already inaugurated a committee for the Biafra restoration declaration process in January 2024.[10]

On 24 June 2024, the Organization of Emerging African States, OEAS endorsed the referendum.[118][119]

BRGIE intends to issue a "declaration of the restoration of independent state of Biafra" on December 2, 2024, at the 2024 Finland convention.[120][121] A former U.S. Congressman Jim Moran advocates for Biafra independence under the BRGIE with a contract that has been in effect since June 15, 2024.[122][123]

In emulation of the Lithuania historical part on the Act of the Re-Establishment of the State of Lithuania that restored Lithuania as an independent State on 11 March 1990, the Biafra restoration declaration Act was enacted with the term "Declaration of the restoration of the independent State of Biafra" adopted. The recruitment process for the drafting board to be responsible for the restoration declaration of independence was opened on 2 January 2024.[124][125]

See also

[edit]- Insurgency in Southeastern Nigeria

- Ambazonia

- Half of a Yellow Sun by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

- Pakistanization

- 2023 Nigerien Crisis

- Roland the Headless Thompson Gunner, a song by Warren Zevon that references the state

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Smith, Daniel Jordan (3 March 2011). "Legacies of Biafra: Marriage, 'Home People' and Reproduction Among the Igbo of Nigeria". Africa. 75 (1): 30–45. doi:10.3366/afr.2005.75.1.30. S2CID 144755434.

In 1967, following a succession of military coups and interethnic violence, the predominantly Igbo-speaking region of south-eastern Nigeria attempted to secede, declaring the independent state of Biafra

- ^ Nwaka, Jacinta Chiamaka; Osuji, Obiomachukwu Winifred (27 September 2022). "They do not belong: adoption and resilience of the Igbo traditional culture". African Identities. 22 (3): 828–845. doi:10.1080/14725843.2022.2126346. ISSN 1472-5843. S2CID 252583369.

- ^ a b c Minahan, James (2002). Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations. Vol. S–Z. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 762. ISBN 978-0-313-32384-3 – via Google Books.

- ^ "biafra". CollinsDictionary.com. HarperCollins.

- ^ "The Republic of Biafra | AHA". www.historians.org. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ "Republic of Biafra (1967–1970)". 21 June 2009. Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- ^ Anglin, Douglas G. (1971). "Zambia and the Recognition of Biafra". The African Review: A Journal of African Politics, Development and International Affairs. 1 (2): 102–136. ISSN 0856-0056. JSTOR 45341498.

- ^ Daly, Samuel Fury Childs (2020). A History of the Republic of Biafra: Law, Crime, and the Nigerian Civil War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108887748. ISBN 978-1-108-84076-7. S2CID 225266768.

- ^ Lewis, Peter (2007). Oil, Politics, and Economic Change in Indonesia and Nigeria. University of Michigan Press. p. 78. ISBN 9780472024742.

setting in motion a chain of social conflicts that culminated in the attempted secession of Igbo nationalists in 1967

- ^ a b c Ijalaye, David A. (July 1971). "Was 'Biafra' at Any Time a State in International Law?". American Journal of International Law. 65 (3): 553–554. doi:10.1017/S0002930000147311. JSTOR 2198977. S2CID 152122313. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- ^ Hurst, Ryan (21 June 2009). "Republic of Biafra (1967–1970)". Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ^ "Nigeria-Biafra Civil War". Archived from the original on 4 August 2004. Retrieved 18 August 2004.

- ^ Nwangwu, Chikodiri; Onuoha, Freedom C; Nwosu, Bernard U; Ezeibe, Christian (11 December 2020). "The political economy of Biafra separatism and post-war Igbo nationalism in Nigeria". African Affairs. 119 (477): 526–551. doi:10.1093/afraf/adaa025.

- ^ "Map of Africa from 1669". catalog.afriterra.org. Afriterra Foundation. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- ^ "Map of Africa from 1669, Zoom". catalog.afriterra.org (zoomMap). Afriterra Foundation. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- ^ "Map of North-West Africa, 1829". U.T. Libraries. Texas, USA: University of Texas. Archived from the original on 8 August 2009. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- ^ Zedler, Johann Heinrich. "Grosses vollständiges Universal-Lexicon aller Wissenchafften und Künste". Bavarian State Library. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

page 1684

- ^ "1730 map – L'Isle, Guillaume de, 1675–1726". Princeton, New Jersey, USA: Princeton University Library. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

- ^ Thomas, Charles W. (1860). Adventures and observations on the west coast of Africa, and its islands. Historical and descriptive sketches of Madeira, Canary, Biafra, and Cape Verd islands; their climates, inhabitants, and productions. Accounts of places, peoples, customs, trade, missionary operations, etc., on that part of the African coast lying between Tangier, Morocco, and Benguela, by Rev. Chas. W. Thomas ... with illustrations from original drawings – via University of Michigan libraries.

- ^ a b Philips, Barnaby (13 January 2000). "Biafra: Thirty years on". BBC News. Archived from the original on 30 September 2009. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- ^ a b Plotnicov, Leonard (August 1971). "An Early Nigerian Civil Disturbance: The 1945 Hausa-Ibo riot in Jos". The Journal of Modern African Studies. 9 (2): 297–305. doi:10.1017/S0022278X00024976. ISSN 1469-7777. JSTOR 159448. S2CID 154565379; also cited as ISSN 0022-278X

- ^ a b c "What is wrong with Nigeria?". Indigenous People of Biafra USA. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- ^ Diamond, Larry (1988). "Crisis and Conflict in the Western Region, 1962–63". Class, Ethnicity and Democracy in Nigeria. pp. 93–130. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-08080-9_4. ISBN 978-1-349-08082-3.[full citation needed]

- ^ Njoku, Hilary M. (1987). A Tragedy without Heroes: The Nigeria-Biafra war. Fourth Dimension. ISBN 9789781562389 – via Google Books.

- ^ Omoigui, Nowa. "Operation 'Aure': The northern military counter-rebellion of July 1966". Nigeria/Africa Masterweb. Archived from the original on 23 July 2008. Retrieved 15 August 2008.

- ^ Bozimo, Willy. "Festus Samuel Okotie Eboh (1912–1966)". Niger Delta Congress. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- ^ "The last of the plotters dies". OnlineNigeria.com. 1966 Coup. 20 March 2007. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ^ a b c d e "Nigeria 1967–1970". Armed Conflict Events Database. onwar.com. Biafran Secession. 16 December 2000. Archived from the original on 5 September 2008. Retrieved 15 August 2008.

- ^ Ojukwu, C.O. "Ojukwu's Declaration of Biafra speech". Citizens for Nigeria. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. Retrieved 15 August 2008.

- ^ "Republic of Biafra is born". Biafra Spotlight. Library of Congress Africa Pamphlet Collection. 2 May 2014. Retrieved 11 May 2014 – via Flickr.

- ^ "Nigeria buries ex-Biafra leader". BBC News. World News / Africa. 2 March 2012. Archived from the original on 18 June 2018. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ^ "ICE Case Studies". TED. American University. November 1997. Archived from the original on 27 August 2008. Retrieved 16 August 2008.

- ^ Omoigui, Nowa (3 October 2007). "Nigerian Civil War file". dawodu.com. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 27 October 2007.

- ^ "30 June". BBC News. On this Day. 30 June 1969. Archived from the original on 12 June 2009. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- ^ Daly, Samuel Fury Childs (2020). A history of the Republic of Biafra : law, crime, and the Nigerian Civil War. Cambridge, United Kingdom. ISBN 9781108887748.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Jacos, Dan (1 August 1987). "Lest we forget the starvation of Biafra". The New York Times. Opinion. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ eribake, akintayo (14 January 2016). "50 yrs after January 15 1966 coup: Excerpts of Major Nzeogwu's coup speech". Vanguard News. Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- ^ Philips, Barnaby (13 January 2000). "Biafra: Thirty years on". BBC News. Archived from the original on 15 December 2013. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ Mwalimu, Charles (2005). The Nigerian Legal System. Peter Lang. ISBN 9780820471266 – via Google Books.

- ^ Made, Alexsa (9 January 2013). "Group sues FG over abandoned property, others". Vanguard News, Nigeria. Biafra. Archived from the original on 26 March 2013. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- ^ "Nigeria security forces extort N100 billion in Southeast in three years". Indigenous People of Biafra USA. Archived from the original on 25 April 2019. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- ^ "Nigeria". Britannica. Archived from the original on 30 June 2008. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- ^ Nwázùé, Ònyémà. "Introduction to the Igbo Language". Igbonet.com. Archived from the original on 18 August 2008. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ^ Daly, Samuel Fury Childs (2020). A History of the Republic of Biafra: Law, Crime, and the Nigerian Civil War. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-84076-7.

- ^ McCormack, Fergus (4 December 2016). "Flights of angels". Would you believe?. RTÉ Press Centre. Archived from the original on 23 January 2018. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ Staunton, Enda (Autumn 2000). "The forgotten war". History Ireland magazine. Vol. 8, no. 3. Archived from the original on 22 January 2018. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ Phillips, James F. (2018). "Biafra at 50 and the birth of Emergency Public Health". American Journal of Public Health. 108 (6): 731–733. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2018.304420. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 5944891. PMID 29741940.

- ^ "Fifty Years Later: U.S. Intelligence Shortcomings in the Nigerian Civil War". Council on Foreign Relations.

- ^ McNeil, Brian (3 July 2014). "'And starvation is the grim reaper': the American Committee to Keep Biafra Alive and the genocide question during the Nigerian civil war, 1968–70". Journal of Genocide Research. 16 (2–3): 317–336. doi:10.1080/14623528.2014.936723. S2CID 70911056.

- ^ Whalen, Emily (5 December 2016). "Foreign Policy from Candidate to President: Richard Nixon and the Lesson of Biafra". Not Even Past.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Symes, Peter (1997). "The bank notes of Biafra". International Bank Note Society Journal. 36 (4). Archived from the original on 27 August 2008. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- ^ Ivwurie, Dafe (25 February 2011). "Nigeria: The men who may be President (1)". AllAfrica.com. Archived from the original on 14 December 2013. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ^ "Operation Biafra Babies". canit.se. Archived from the original on 14 October 2008. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- ^ Steiner, Rolf (1978). The Last Adventurer. Boston, MA: Little, Brown.

- ^ a b Jowett, Philip (2016). Modern African Wars (5): The Nigerian-Biafran War 1967–70. Oxford: Osprey Press. ISBN 978-1472816092.

- ^ Robson, Michael. "The Douglas A/B-26 Invader – Biafran Invaders". Vectaris.net. Archived from the original on 9 May 2013. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ^ Jowett, Philip (2016). Modern African Wars (5): The Nigerian-Biafran War 1967–70. Oxford: Osprey Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-1472816092.

- ^ Venter, Al J. (2015). Biafra's War 1967-1970: A tribal conflict in Nigeria that left a million dead. Helion & Company. p. 137. ISBN 978-1-910294-69-7.

- ^ "Biafra Babies". ordendebatalla.org (blog). October 2015. Archived from the original on 22 April 2019. Retrieved 22 April 2019.

- ^ Vidal, Joao M. (September–October 1996). "Texans in Biafra T-6Gs in use in the Nigerian Civil War". Air Enthusiast. No. 65. pp. 40–47.

- ^ "Founding of Médecins Sans Frontières". Doctors without borders. Archived from the original on 20 December 2015. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- ^ Bortolotti, Dan (2004). Hope in Hell: Inside the world of Doctors without Borders. Firefly Books. ISBN 1-55297-865-6.

- ^ "World Health Organization" (PDF). World Health Organization. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 August 2011. Retrieved 30 November 2017. Fulltext of Chapter 17, "West and Central Africa", from Smallpox and its eradication (1988), F. Fenner ... [et al.]. World Health Organization.

- ^ Hult, Martin; Tornhammar, Per; Ueda, Peter; Chima, Charles; Edstedt Bonamy, Anna-Karin; Ozumba, Benjamin; Norman, Mikael (2010). "Hypertension, diabetes and overweight: Looming legacies of the Biafran famine". PLOS ONE. 5 (10): e13582. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...513582H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013582. PMC 2962634. PMID 21042579.

- ^ "Nigeria: Those born during Biafra famine are susceptible to obesity, study finds". The New York Times. 2 November 2010. Archived from the original on 7 October 2015. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- ^ Akresh, Richard; Bhalotra, Sonia; Leone, Marinella; Osili, Una O. (August 2017). First and second generation impacts of the Biafran war (PDF) (Report). doi:10.3386/w23721. NBER Working Paper No. 23721.

- ^ Duruji, Moses Metumara (December 2012). "Resurgent ethno-nationalism and the renewed demand for Biafra in south-east Nigeria" (PDF). National Identities. 14 (4): 329–350. Bibcode:2012NatId..14..329D. doi:10.1080/14608944.2012.662216. ISSN 1460-8944. S2CID 144289500. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- ^ Shirbon, Estelle (12 July 2006). "Dream of free Biafra revives in southeast Nigeria". Boston Globe. Reuters. Archived from the original on 10 December 2008. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- ^ "Biafra News". Biafra.cwis.org. 13 April 2009. Archived from the original on 10 October 2010. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ^ Heerten, Lasse; Moses, A. Dirk (3 July 2014). "The Nigeria–Biafra war: Postcolonial conflict and the question of genocide". Journal of Genocide Research. 16 (2–3): 169–203. doi:10.1080/14623528.2014.936700. S2CID 143878825.

- ^ "Half a century after the war, angry Biafrans are agitating again". The Economist. 28 November 2015. Archived from the original on 29 November 2015. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- ^ "WEST AFRICA IRIN-WA Weekly Round-up 22". Iys.cidi.org. 2 June 2000. Archived from the original on 18 April 2009. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ^ "Emerging genocide in Nigeria". Cwis.org. Archived from the original on 27 January 2010. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ^ "Chronicles of brutality in Nigeria 2000–2006". Cwis.org. Archived from the original on 18 April 2012. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ^ "MASSOB launches "Biafran Int'l Passport" to celebrate 10th anniversary". Vanguard News, Nigeria. 1 July 2009. Archived from the original on 2 March 2010. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ^ "Court determines suit between Nigeria, Biafra on Sept 22". sunnewsonline.com. 18 July 2015. Archived from the original on 7 August 2015. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- ^ "Uwazuruike reveals why he sacked Kanu from MASSOB". Punch Nigeria. 11 January 2017. p. 29. Archived from the original on 17 January 2019. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ Murray, Senan (3 May 2007). "Reopening Nigeria's civil war wounds". BBC News. Archived from the original on 27 December 2008. Retrieved 15 August 2008.

- ^ "Radio Biafra transmitters found ..." PUO Reports. November 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Radio Biafra container with massive transmitter found in Nnamdi Kanu's village". News Rescue. 17 November 2015. Archived from the original on 19 November 2015. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- ^ "Nigeria separatist resurfaces in Israel". BBC News. 22 October 2018. Archived from the original on 23 March 2019. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- ^ "FG files fresh treason charges against Nnamdi Kanu". This Day Live. Archived from the original on 24 December 2015.

- ^ "African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights". Nigeria-Law.org. Archived from the original on 16 June 2018. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- ^ "Biafra will not stand, Buhari vows". Vanguard News, Nigeria. 6 March 2016. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- ^ "Nigeria: At least 150 peaceful pro-Biafra activists killed in chilling crackdown". Amnesty International. 24 November 2016. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- ^ "Amnesty accuses Nigerian army of killing at least 17 unarmed Biafran separatists". Reuters. 10 June 2016. Archived from the original on 11 January 2018.

- ^ "Troops clash with militants, pirates in Niger delta creeks". The National Online. 9 November 2016.

- ^ "Police release arrested Biafra leader". Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ^ "Police detain Biafra Youth League leader in Calabar". News Express Nigeria. Archived from the original on 16 December 2019. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ^ "Biafra anglophone secession tension heightens in border towns". New Telegraph Nigeria. December 2017. Archived from the original on 16 December 2019. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ^ "Southern Cameroun joins IPOB in Biafra struggle". Sun News Online. 18 April 2017.

- ^ "Biafra National Council inauguration; police arrest 100 Youth League members in Yenegoa". Daily Times, Nigeria. Breaking news. 17 August 2019. Archived from the original on 16 December 2019. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ^ "Police strikes as Asari Dokubo inaugurates Biafra National Council, arrest Biafra youths". News Express Nigeria. Archived from the original on 16 December 2019. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ^ "Biafra: Police free 100 agitators arrested during meeting with Asari Dokubo". Daily Post, Nigeria. 18 August 2019.

- ^ "Court fixes February to hear suit seeking Biafra republic". The Guardian, Nigeria. 30 November 2018. Archived from the original on 30 November 2018. Retrieved 30 November 2018.[needs update]

- ^ "UNPO welcomes 5 new members!". Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (UNPO). unpo.org. United Nations (UN). 3 August 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ "Guam: Territory to be inducted into UNPO". Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (UNPO). unpo.org. United Nations (UN). 31 July 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ Reporter, Staff (6 October 2017). "Mystery of the missing Biafran separatist". The Mail & Guardian. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ Leavitt, Jericho (8 November 2023). "Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB)". The Modern Insurgent. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ "Biafra quest fuels Nigeria conflict: Too scared to marry and bury bodies". 9 January 2023. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ Odeh, Nehru. "IPOB: Why Nnamdi Kanu, Uche Mefor are at war". PM News.

- ^ "Biafran leader Nnamdi Kanu: The man behind Nigeria's separatists". BBC News. 5 May 2017. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ Oko, Steve. "Proscription, designation of IPOB as terror organisation, unconstitutional – Court". Vanguard Nigeria.

- ^ Elusoji, Solomon. "We Didn't Designate IPOB As Terrorist Organisation – UK". Channels TV.

- ^ X (30 April 2019). "The dream of Biafra lives on in underground Nigerian radio broadcasts". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ Writer, Conor Gaffey Staff (7 December 2015). "What is Biafra and Why are Some Nigerians Calling for Independence?". Newsweek. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ "Nigeria: At least 150 peaceful pro-Biafra activists killed in chilling crackdown". Amnesty International. 24 November 2016. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ "Biafra Republic Government in Exile". Biafra Republic Government in Exile. 6 June 2023. Retrieved 18 June 2023.

- ^ Uchechukwu, Oghenekevwe UCHECHUKWU (11 April 2023). "Ekpa declares self Biafra Prime Minister in Exile, names advisory council". ICIR. Retrieved 11 March 2024.

- ^ Rämö, Aurora (21 March 2024). ""Biafran pääministeri" asuu Lahdessa – Erikoinen kokoomusvaikuttaja aiheutti diplomaattisen selkkauksen" [The "prime minister of Biafra" lives in Lahti - A peculiar coalition influencer caused a diplomatic row [Google translate]]. Suomen Kuvalehti (in Finnish). Retrieved 14 April 2024.

- ^ Staff, Daily Post (12 March 2024). "Simon Ekpa's journey from track athlete to Prime Minister of Biafra Republic Government in Exile". Daily Post Nigeria. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ Ariemu, Ogaga (26 August 2023). "Simon Ekpa, Biafra Republic Government in Exile opens administrative office in US". Daily Post Nigeria. Retrieved 1 March 2024.

- ^ Ariemu, Ogaga (19 October 2023). "Simon Ekpa hosts three-day extraordinary conference on Biafra Referendum". Daily Post Nigeria. Retrieved 28 February 2024.

- ^ "Biafra: BRGIE begins self-referendum voting for all Igbos, reveals details". Nigerian Pilot News. 1 February 2024. Retrieved 1 March 2024.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Amin_3 (1 February 2024). "Biafra: BRGIE begins self-referendum voting for all Igbos, reveals details - Peoples Daily Newspaper". Retrieved 1 March 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Ndubuisi, Victor (10 February 2024). "Over 2million Biafrans Set To Vote For Self-Referendum In Few Days – Simon Ekpa". AnaedoOnline. Retrieved 1 March 2024.

- ^ "'We're ready to go' as over 2m Biafrans vote for self-referendum in few days - Ekpa". Daily Post Nigeria. 10 February 2024. Retrieved 1 March 2024.

- ^ Ariemu, Ogaga (28 June 2024). "Biafra referendum binding statement under Int'l law - OEAS". Daily Post Nigeria. Retrieved 28 June 2024.

- ^ Godspower, Samuel (26 June 2024). "International NGO endorses Biafra's self-determination, total independence". Retrieved 28 June 2024.

- ^ Amin_3 (7 April 2024). "Insecurity surge: Biafra declaration in December remains sacrosanct- BRGIE assures - Peoples Daily Newspaper". Retrieved 23 June 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Rämö, Aurora (21 March 2024). ""Biafran pääministeri" asuu Lahdessa – Erikoinen kokoomusvaikuttaja aiheutti diplomaattisen selkkauksen". Suomenkuvalehti.fi. Retrieved 23 June 2024.

- ^ Grace, Ihesiulo (21 June 2024). "US ex-congressman Moran advocates for Biafra Independent under BRGIE". DAILY TIMES Nigeria. Retrieved 23 June 2024.

- ^ Ariemu, Ogaga (22 June 2024). "US ex-Congressman, Moran backing Biafra Independence - BRGIE claims". Daily Post Nigeria. Retrieved 23 June 2024.

- ^ "Separatist Leader Announces Recruitment For Board To Declare Secession From Nigeria - Heritage Times". 2 January 2024. Retrieved 1 March 2024.

- ^ Amin_3 (8 January 2024). "BRGIE unveils date to declare Biafra independence - Peoples Daily Newspaper". Retrieved 1 March 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

Further reading

[edit]- Daly, Samuel Fury Childs (2020). A History of the Republic of Biafra: Law, Crime, and the Nigerian Civil War. Cambridge University Press. — online review

- Hersh, Seymour M. The Price of Power, Kissinger in the Nixon White House. pp. 141–146.

External links

[edit]- "Republic of Biafra collection c. 1968–1970". EU Libraries. Emory University. 1968–1970. "Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library".

- Biafra

- 1967 establishments in Nigeria

- 1970 disestablishments in Nigeria

- Former territorial entities in Africa

- Former countries in Africa

- Former republics

- Former unrecognized countries

- History of Igboland

- Nigerian Civil War

- Separatism in Nigeria

- States and territories disestablished in 1970

- States and territories established in 1967

- Members of the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization