Centennial Olympic Park bombing

| Centennial Olympic Park Bombing | |

|---|---|

| Part of terrorism in the United States | |

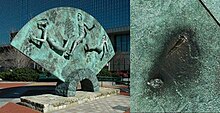

Bomb fragment mark on Olympic Park sculpture | |

| Location | Atlanta, Georgia, United States |

| Coordinates | 33°45′38″N 84°23′33″W / 33.76065°N 84.392583°W |

| Date | July 27, 1996 1:20 am (EDT) |

| Target | Centennial Olympic Park |

Attack type | Bombing |

| Weapons | Pipe bomb |

| Deaths | 2 (1 directly, 1 indirectly) |

| Injured | 111 |

| Perpetrator | Eric Rudolph |

| Motive | Christian terrorism, Far-right extremism, anti-abortion violence |

The Centennial Olympic Park bombing was a domestic terrorist pipe bombing attack on Centennial Olympic Park in Atlanta, Georgia, on Saturday, July 27, 1996, during the Summer Olympics. The blast directly killed one person and injured 111 others; another person later died of a heart attack. It was the first of four bombings committed by Eric Rudolph in a terrorism campaign against the U.S. government which he accused of championing "the ideals of global socialism" and "abortion on demand".[1][2] Security guard Richard Jewell discovered the bomb before detonation, notified Georgia Bureau of Investigation officers, and began clearing spectators out of the park along with other security guards.

After the bombing, Jewell was initially investigated as a suspect by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and news media aggressively focused on him as the presumed culprit when he was actually innocent. In October 1996, the FBI declared Jewell was no longer a person of interest. Following three more bombings in 1997 and 1998, Rudolph was identified by the FBI as the suspect. In 2003, Rudolph was finally captured and arrested, and in 2005 he agreed to plead guilty to avoid a potential death sentence. Rudolph was sentenced to life imprisonment without parole for his crimes.[3]

Bombing

[edit]

Centennial Olympic Park was designed as the "town square" of the Olympics, and thousands of spectators had gathered for a late concert by the band Jack Mack and the Heart Attack. Sometime after midnight, Rudolph planted a green U.S. military ALICE pack (field pack) containing three pipe bombs filled with smokeless powder surrounded by three-inch-long (7.6 cm) masonry nails, which caused the death of one victim and most of the human injuries, underneath a bench near the base of a concert sound tower.[4] He then left the area.

The pack had a directed charge and could have done more damage but it was slightly moved at some point.[5] It used a steel plate as a directional device.[6] Investigators later tied the Sandy Springs and Otherside Lounge bombs together with this first device because all were propelled by nitroglycerin dynamite, used an alarm clock and Rubbermaid containers, and contained steel plates.[7]

FBI Agent David (Woody) Johnson received notice that a call to 911 was placed about 18 minutes before the bomb detonated warning that a bomb would go off at the park within 30 minutes by "a white male with an indistinguishable American accent".[8]

Security guard Richard Jewell discovered the bag underneath a bench and alerted Georgia Bureau of Investigation officers.[9] Tom Davis, of the Georgia Bureau of Investigation, called in a bomb squad, including members of the ATF and FBI to investigate the suspicious bag, which was leaning against the 40-ft NBC sound tower.[8] Jewell and other security guards began clearing the immediate area so that the bomb squad could investigate the suspicious package. The bomb detonated two to three minutes into the evacuation, before all spectators could leave the area.[8]

The first one who gave the news live worldwide was the Italian reporter Ezio Luzzi, who was in Atlanta as a correspondent of RAI Radiotelevisione Italiana for the Olympic Games that were taking place at that time.[citation needed]

Video of the explosion from a short distance away was captured by Robert Gee, a tourist from California, and later aired by CNN.[10] The sound of the explosion was also recorded by a news crew from the German public television network ARD, who were interviewing American swimmer Janet Evans at a nearby hotel.[11][12]

Victims

[edit]Alice Hawthorne, 44, of Albany, Georgia, was killed in the explosion when a nail from the bomb penetrated her skull and riddled her body with shrapnel while she was standing with her 14-year-old daughter who was badly injured.[9][13] A cameraman with Turkish Radio and Television Corporation, Melih Uzunyol, 40, who had "survived coverage of wars in Azerbaijan, Bosnia and the Persian Gulf," suffered a fatal heart attack while running to the scene.[14][15] The bomb wounded 111 others.

Reaction

[edit]

President Bill Clinton denounced the explosion as an "evil act of terror" and vowed to do everything possible to track down and punish those responsible.[16]

Despite the event, officials and athletes agreed that the games should continue as planned.

Aftermath

[edit]Richard Jewell falsely implicated

[edit]Though Richard Jewell was hailed as a hero for his role in discovering the bomb and moving spectators to safety, news organizations later reported that Jewell was considered a potential suspect in the bombing, four days afterward, and shortly after a brief, mistaken detainment of two juvenile persons of interest at the Kensington MARTA station. Jewell, at the time, was unknown to authorities, and a lone wolf profile made sense to FBI investigators after they were contacted by his former employer at Piedmont College.

Jewell was named as a person of interest, although he was never arrested. Jewell's home was searched, his background exhaustively investigated, and he became the subject of intense media interest and surveillance, including a media siege of his home.[5]

After Jewell was exonerated, he initiated defamation lawsuits against NBC News, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, and other media entities, and insisted on a formal apology from them. Jewell's lawsuit accused Piedmont College President Raymond Cleere of falsely describing Jewell as a "badge-wearing zealot" who "would write epic police reports for minor infractions".[17] The cases were later settled after 15 years of litigation with the Georgia Court of Appeals decision in July 2012, that the newspapers accurately reported that Jewell was the key suspect in the bombing, and emphasized he was only a suspect and the potential issues in the law enforcement case against him.[18] Richard Jewell died on August 29, 2007, at the age of 44 from serious medical problems related to diabetes.[19]

Richard Jewell, a biographical drama film, was released in the United States on December 13, 2019.[20] The film was directed and produced by Clint Eastwood. It was written by Billy Ray, based on the 1997 article "American Nightmare," and the book The Suspect: An Olympic Bombing, the FBI, the Media, and Richard Jewell, the Man Caught in the Middle (2019) by Kent Alexander and Kevin Salwen.[21][22][23][24][25] Jewell is played by Paul Walter Hauser.

A TV series, Manhunt, also called ManHunt: Deadly Games, dedicated season 2 (2020) to the story of Richard Jewell. Jewell is played by Cameron Britton.[26]

Conviction of Eric Robert Rudolph

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2020) |

After Jewell was cleared, the FBI admitted it had no other suspects, and the investigation made little progress until early 1997, when two more bombings took place, at an abortion clinic and a lesbian nightclub, both in the Atlanta area. Similarities in the bomb design allowed investigators to conclude that this was the work of the same perpetrator. One more bombing of an abortion clinic, this time in Birmingham, Alabama, which killed a policeman working as a security guard and seriously injured nurse Emily Lyons,[1] gave the FBI crucial clues including a partial license plate.

The plate and other clues led the FBI to identify Eric Robert Rudolph, a carpenter and handyman, as a suspect. Rudolph eluded capture and became a fugitive; officials believed he had disappeared into the rugged southern Appalachian Mountains, familiar from his youth. On May 5, 1998, the FBI named him as one of its ten most wanted fugitives and offered a $1 million reward for information leading directly to his arrest. On October 14, 1998, the Department of Justice formally named Rudolph as its suspect in all four bombings.

After more than five years on the run, Rudolph was arrested on May 31, 2003, in Murphy, North Carolina, by a rookie police officer, Jeffrey Scott Postell of the Murphy Police Department behind a Save-A-Lot store at about 4 a.m.; Postell, on routine patrol, had originally suspected a burglary in progress.[27] On April 8, 2005, the government announced Rudolph would plead guilty to all four bombings, including the Centennial Olympic Park attack. Rudolph is serving four life terms[1] without the possibility of parole at ADX Florence supermax prison in Florence, Colorado.

Rudolph's justification for the bombings according to his April 13, 2005 statement, was political:[2]

- In the summer of 1996, the world converged upon Atlanta for the Olympic Games. Under the protection and auspices of the regime in Washington, millions of people came to celebrate the ideals of global socialism. Multinational corporations spent billions of dollars, and Washington organized an army of security to protect these best of all games. Even though the conception and purpose of the so-called Olympic movement is to promote the values of global socialism, as perfectly expressed in the song "Imagine" by John Lennon, which was the theme of the 1996 Games even though the purpose of the Olympics is to promote these ideals, the purpose of the attack on July 27 was to confound, anger and embarrass the Washington government in the eyes of the world for its abominable sanctioning of abortion on demand.

- The plan was to force the cancellation of the Games,[1] or at least create a state of insecurity to empty the streets around the venues and thereby eat into the vast amounts of money invested.

On August 22, 2005, Rudolph, who had previously received a life sentence for the Alabama bombing, was sentenced to three concurrent terms of life imprisonment without parole for the Georgia incidents. Rudolph read a statement at his sentencing in which he apologized to the victims and families only of the Centennial Park bombing, reiterating that he was angry at the government and hoped the Olympics would be canceled. At his sentencing, fourteen other victims or relatives gave statements, including the widower of Alice Hawthorne.

Rudolph's former sister-in-law, Deborah Rudolph, talked about the irony of Rudolph's plea deal putting him in custody of a government he hates. "Knowing that he's living under government control for the rest of his life, I think that's worse to him than death," she told the San Diego Union Tribune in 2005.

In February 2013, LuLu.com published Rudolph's book, Between the Lines of Drift: The Memoirs of a Militant, and in April 2013 the U.S. Attorney General seized his $200 royalty to help pay off the $1 million that Rudolph owes in restitution to the state of Alabama.[28]

See also

[edit]- Domestic terrorism in the United States

- Boston Marathon bombing, another bombing at an American sporting event

Other incidents of violence during the Olympic games:

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Gross, Doug (April 14, 2005). "Eric Rudolph Lays Out the Arguments that Fueled His Two-Year Bomb Attacks". San Diego Union-Tribune. Associated Press. Archived from the original on September 2, 2018. Retrieved March 27, 2019.

- ^ a b "Full Text of Eric Rudolph's Confession". NPR (National Public Radio). April 14, 2005. Retrieved December 6, 2013.

- ^ "CNN.com - Rudolph agrees to plea agreement - Apr 8, 2005". www.cnn.com. Retrieved March 26, 2024.

- ^ "20 years later, I still lose sleep over the Centennial Olympic Park bombing. Here's why". myajc. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- ^ a b Brenner, Marie (February 1997). "American Nightmare: The Ballad of Richard Jewell". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on January 18, 2015. Retrieved December 6, 2013.

- ^ Brown, Aaron & Harris, Art (February 7, 2001). "The Hunt for Eric Rudolph". CNN Presents. CNN. Retrieved December 6, 2013.

- ^ Freeman, Scott (August 24, 2006). "A Hero In His Own Mind". Orlando Weekly. Archived from the original on December 12, 2013. Retrieved December 6, 2013.

- ^ a b c "When Terror Struck the Summer Olympics 20 Years Ago". Time. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- ^ a b "Olympic park bombing brought terror close to home". politics.myajc. Archived from the original on January 24, 2018. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- ^ Shales, Tom (July 26, 1996). "TV Networks Sprint Into Action". The Washington Post. p. A26. Retrieved May 31, 2019.

- ^ "JANET EVANS NEARBY DURING CENTENNIAL PARK EXPLOSION". Deseret News / Associated Press. July 27, 1996. Archived from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved August 12, 2016.

- ^ Mackay, Duncan (July 15, 2016). "Janet Evans to return to Atlanta as part of 20th anniversary celebrations for 1996 Olympics". Inside the Games. Retrieved August 12, 2016.

- ^ Poole, Shelia. "Daughter of Olympic bombing victim: 'It was a terrible, terrible day'". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

- ^ "BOMB AT THE OLYMPICS; Heart Ailment Kills War Survivor in Altanta [sic]". The New York Times. July 28, 1996. Retrieved August 26, 2020.

- ^ Jacobs, Jeff (July 28, 1996). "In Atlanta, Fear Roams Hand In Hand With Anger". Hartford Courant. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016.

- ^ "Clinton Pledges Thorough Effort to Find Olympic Park Bomber". CNN. July 27, 1996. Retrieved December 6, 2013.

- ^ "Ex-Suspect in Bombing Sues Newspapers, College: Jewell's Libel Claim Seeks Unspecified Damages". The Washington Post. January 29, 1997. Archived from the original on October 20, 2012. Retrieved December 6, 2013.

- ^ "Ga. court upholds ruling in Jewell suit". ajc. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- ^ Sack, Kevin (August 30, 2007). "Richard Jewell, 44, Hero of Atlanta Attack, Dies". The New York Times.

Richard A. Jewell, whose transformation from heroic security guard to Olympic bombing suspect and back again came to symbolize the excesses of law enforcement and the news media, died Wednesday at his home in Woodbury, Georgia. The cause of death was not released, pending the results of an autopsy that will be performed by the Georgia Bureau of Investigation. But the coroner in Meriwether County said that Jewell died of natural causes and that he had battled serious medical problems since learning that he had diabetes in February.

- ^ Ramos, Dino-Ray (October 8, 2019). "Clint Eastwood's 'Richard Jewell' To Make World Premiere At AFI Fest". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved October 9, 2019.

- ^ Climek, Chris. "Review: 'Richard Jewell' Clears One Name While Smearing Another". NPR. Retrieved December 13, 2019.

- ^ Brenner, Marie (February 1997). "American Nightmare: The Ballad of Richard Jewell". Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ Kent Alexander and Kevin Salwen (2019). The Suspect: An Olympic Bombing, the FBI, the Media, and Richard Jewell, the Man Caught in the Middle, Abrams, ISBN 1683355245.

- ^ "Stop defending an irresponsible movie and start apologising | Benjamin Lee | Film". The Guardian. December 13, 2019. Retrieved December 14, 2019.

- ^ Marc Tracy (December 12, 2019). "Clint Eastwood's 'Richard Jewell' Is at the Center of a Media Storm". The New York Times. Retrieved December 14, 2019.

- ^ "ManHunt". IMDb.

- ^ "Atlanta Olympic Bombing Suspect Arrested". CNN. May 31, 2003.

- ^ Faulk, Kent (April 8, 2013). "Birmingham Abortion Clinic Bomber Eric Robert Rudolph Fights to Get Profits from His Book". AL.com.

External links

[edit]- FBI Centennial Park Bombing page via the Wayback Machine, from December 2, 1998.

- 1996 Summer Olympics

- 1996 murders in the United States

- 1996 in Georgia (U.S. state)

- 1996 in Atlanta

- July 1996 crimes in the United States

- Attacks in the United States in 1996

- Crime in Atlanta

- Counterterrorism in the United States

- Religiously motivated violence in the United States

- Christian terrorism in the United States

- Improvised explosive device bombings in the United States

- Filmed improvised explosive device bombings

- Olympic deaths

- Murder in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Terrorist incidents in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Terrorist incidents in the United States in 1996

- Crimes in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives