Lee Harvey Oswald

Lee Harvey Oswald | |

|---|---|

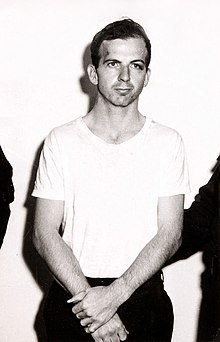

Oswald on November 23, 1963, one day after the assassination of U.S. president John F. Kennedy | |

| Born | October 18, 1939 New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Died | November 24, 1963 (aged 24) Parkland Hospital, Dallas, Texas, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Gunshot wound |

| Resting place | Rose Hill Cemetery, Fort Worth, Texas, U.S. 32°43′57″N 97°12′12″W / 32.732455°N 97.203223°W |

| Known for | Assassination of John F. Kennedy and murder of Dallas police officer J. D. Tippit |

| Criminal charge | Murder with malice (2 counts) |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 2 |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service | United States Marine Corps |

| Years of service | 1956–1959 |

| Rank | Private first class (demoted to private) |

| Signature | |

Lee Harvey Oswald (October 18, 1939 – November 24, 1963) was a U.S. Marine veteran who assassinated John F. Kennedy, the 35th president of the United States, on November 22, 1963.

Oswald was placed in juvenile detention at the age of 12 for truancy, during which time he was assessed by a psychiatrist as "emotionally disturbed" due to a lack of normal family life. He attended 12 schools in his youth, quitting repeatedly, and at the age of 17 he joined the Marines, where he was court-martialed twice and jailed. In 1959, he was discharged from active duty into the Marine Corps Reserve, then flew to Europe and defected to the Soviet Union. He lived in Minsk, Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic, married a Russian woman named Marina, and had a daughter. In June 1962, he returned to the United States with his wife, and eventually settled in Dallas, Texas, where their second daughter was born.

Oswald shot and killed Kennedy on November 22, 1963, from a sixth-floor window of the Texas School Book Depository as Kennedy traveled by motorcade through Dealey Plaza in Dallas. About 45 minutes after assassinating Kennedy, Oswald shot and killed Dallas police officer J. D. Tippit on a local street. He then slipped into a movie theater, where he was arrested for Tippit's murder. Oswald was charged with the assassination of Kennedy, but he denied responsibility for the killing, claiming that he was a "patsy". Two days later, Oswald was fatally shot by local nightclub owner Jack Ruby on live television in the basement of Dallas Police Headquarters.

In September 1964, the Warren Commission concluded that Oswald had acted alone when assassinating Kennedy. This conclusion, though controversial, was supported by investigations from the Dallas Police Department, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the United States Secret Service, and the House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA).[n 1][1][2] Despite forensic, ballistic, and eyewitness accounts supporting the official findings, public opinion polls have shown that most Americans still do not believe that the official version tells the whole truth of the events,[3] and the assassination spawned numerous conspiracy theories.

Early life

Oswald was born at the old French Hospital in New Orleans, Louisiana, on October 18, 1939, to a MetLife worker Robert Edward Lee Oswald Sr. (1896–1939) and a legal clerk Marguerite Frances Claverie (1907–1981).[4] Robert Oswald was a third cousin of President Theodore Roosevelt and a distant cousin of Confederate general Robert E. Lee and served as a sergeant in the U.S. Army during World War I.[5][6] Robert died of a heart attack two months before Lee was born.[7] Lee's elder brother Robert Jr. (1934–2017)[8] was a U.S. Marine during the Korean War.[9] Through Marguerite's first marriage to Edward John Pic Jr., Lee and Robert Jr. were the half-brothers of U.S. Air Force veteran John Edward Pic (1932–2000).[10]

In 1944, Marguerite moved the family from New Orleans to Dallas, Texas. Oswald entered the first grade in 1945 and over the next six years attended several different schools in the Fort Worth areas through the sixth grade. Oswald took an IQ test in the fourth grade and scored 103; "on achievement tests in [grades 4 to 6], he twice did best in reading and twice did worst in spelling".[11]

As a child, Oswald was described as withdrawn and temperamental by several people who knew him.[12] When Oswald was 12 in August 1952, his mother took him to New York City where they lived for a short time with Oswald's half-brother, John. Oswald and his mother were later asked to leave after an argument in which Oswald allegedly struck his mother and threatened John's wife with a pocket knife.[13][14][15]

Oswald attended seventh grade in the Bronx, New York, but was often truant, which led to a psychiatric assessment at a juvenile reformatory.[16][17] The reformatory psychiatrist, Dr. Renatus Hartogs, described Oswald as immersed in a "vivid fantasy life, turning around the topics of omnipotence and power, through which [Oswald] tries to compensate for his present shortcomings and frustrations". Hartogs concluded:

Lee has to be diagnosed as "personality pattern disturbance with schizoid features and passive-aggressive tendencies". Lee has to be seen as an emotionally, quite disturbed youngster who suffers under the impact of really existing emotional isolation and deprivation, lack of affection, absence of family life and rejection by a self involved and conflicted mother.[17]

Hartogs recommended that Lee be placed on probation on condition that he seek help and guidance through a child guidance clinic, and that Oswald seek "psychotherapeutic guidance through contact with a family agency". Evelyn D. Siegel, a social worker who interviewed both Lee and Marguerite Oswald at Youth House, while describing "a rather pleasant, appealing quality about this emotionally starved, affectionless youngster which grows as one speaks to him", found that he had detached himself from the world around him because "no one in it ever met any of his needs for love". Hartogs and Siegel indicated that Marguerite gave him very little affection, with Siegel concluding that Lee "just felt that his mother never gave a damn for him. He always felt like a burden that she simply just had to tolerate." Furthermore, his mother did not apparently indicate an awareness of the relationship between her conduct and her son's psychological problems, with Siegel describing Marguerite as a "defensive, rigid, self-involved person who had real difficulty in accepting and relating to people" and who had "little understanding" of Lee's behavior and of the "protective shell he has drawn around himself". Hartogs reported that she did not understand that Lee's withdrawal was a form of "violent but silent protest against his neglect by her and represents his reaction to a complete absence of any real family life".[17]

When Oswald returned to school for the 1953 Fall semester, his disciplinary problems continued. When he failed to cooperate with school authorities, they sought a court order to remove him from his mother's care so he could be placed into a home for boys to complete his education. This was postponed, perhaps partially because his behavior abruptly improved.[17][18] Before the New York family court system could address their case,[17][19] the Oswalds left New York in January 1954, and returned to New Orleans.[17][20]

Oswald completed the eighth and ninth grades in New Orleans. He entered the tenth grade in 1955 but quit school after one month.[21] After leaving school, Oswald worked for several months as an office clerk and messenger in New Orleans. In July 1956, Oswald's mother moved the family to Fort Worth, Texas, and Oswald re-enrolled in the tenth grade for the September session at Arlington Heights High School in Fort Worth. A few weeks later in October, Oswald quit school at age 17 to join the Marines;[22] he never earned a high school diploma. By this point, he had resided at 22 locations and attended 12 schools.[n 2]

Though Oswald had trouble spelling in his youth[11] and may have had a "reading-spelling disability",[23] he read voraciously. By age 15, he considered himself a socialist. According to his diary, "I was looking for a key to my environment, and then I discovered socialist literature. I had to dig for my books in the back dusty shelves of libraries." At 16, he wrote to the Socialist Party of America for information on their Young People's Socialist League, saying he had been studying socialist principles for "well over fifteen months".[24] Edward Voebel, "whom the Warren Commission had established was Oswald's closest friend during his teenage years in New Orleans", said "reports that Oswald was already 'studying Communism' were a 'lot of baloney.'" Voebel said that "Oswald commonly read 'paperback trash'".[25][26]

As a teenager in 1955, Oswald became a cadet member of Civil Air Patrol in New Orleans. Fellow cadets variously recalled him attending CAP meetings "three or four" times, or "10 or 12 times", over a one- to three-month period.[27][28]

Marine Corps

Oswald enlisted in the United States Marine Corps on October 24, 1956, just a week after his seventeenth birthday; because of his age, his brother Robert Jr. was required to sign as his legal guardian. Oswald also named his mother and his half-brother John as beneficiaries.[29] Oswald idolized his older brother Robert Jr.,[30] and wore his Marine Corps ring.[31] John Pic (Oswald's half-brother) testified to the Warren Commission that Oswald's enlistment was motivated by wanting "to get from out and under ... the yoke of oppression from my mother".[32]

Oswald's enlistment papers recite that he was 5 feet 8 inches (1.73 meters) tall and weighed 135 pounds (61 kg), with hazel eyes and brown hair.[29] His primary training was in radar operation, which required a security clearance. A May 1957 document stated that he was "granted final clearance to handle classified matter up to and including confidential after careful check of local records had disclosed no derogatory data".[33]

At Keesler Air Force Base in Mississippi, Oswald finished seventh in a class of thirty in the Aircraft Control and Warning Operator Course, which "included instruction in aircraft surveillance and the use of radar".[34] He was given the military occupational specialty of Aviation Electronics Operator.[35] On July 9, he reported to the Marine Corps Air Station El Toro in California. There he met fellow Marine Kerry Thornley, who co-created Discordianism. Thornley wrote the 1962 fictional book The Idle Warriors based on Oswald. This was the only book written about Oswald before the Kennedy assassination.[36][37][38] Oswald departed for Japan the following month, where he was assigned to Marine Air Control Squadron 1 at Naval Air Facility Atsugi near Tokyo.[39][40]

Like all Marines, Oswald was trained and tested in shooting. In December 1956, he scored 212, which was slightly above the requirements for the designation of sharpshooter.[21] In May 1959 he scored 191, which reduced his rating to marksman.[21][41]

Oswald was court-martialed after he accidentally shot himself in the elbow with an unauthorized .22 caliber handgun.

He was court-martialed a second time for fighting with the sergeant he thought was responsible for his punishment in the shooting matter. He was demoted from private first class to private and briefly imprisoned.

Oswald was later punished for a third incident: while he was on a night-time sentry duty in the Philippines, he inexplicably fired his rifle into the jungle.[42]

Slightly built, Oswald was nicknamed Ozzie Rabbit after the cartoon character; he was also called Oswaldskovich[43] because he espoused pro-Soviet sentiments. In November 1958, Oswald transferred back to El Toro[44] where his unit's function "was to serveil [sic] for aircraft, but basically to train both enlisted men and officers for later assignment overseas". An officer there said that Oswald was a "very competent" crew chief and was "brighter than most people".[45][46]

While Oswald was in the Marines, he taught himself rudimentary Russian. Although this was an unusual endeavor, on February 25, 1959, he was invited to take a Marine proficiency exam in written and spoken Russian. His level at the time was rated "poor" in understanding spoken Russian, though he fared rather reasonably for a Marine private at the time in reading and writing.[47] On September 11, 1959, he received a hardship discharge from active service, claiming his mother needed care. He was placed on the United States Marine Corps Reserve.[21][48][49]

Defection to the Soviet Union

Oswald traveled to the Soviet Union just before he turned 20 in October 1959. He had taught himself Russian and saved $1,500 of his Marine Corps salary (equivalent to $12,500 in 2023).[n 3] Oswald spent two days with his mother in Fort Worth, then embarked by ship on September 20 from New Orleans to Le Havre, France, and immediately traveled to the United Kingdom. Arriving in Southampton on October 9, he told officials he had $700 and planned to stay for one week before proceeding to a school in Switzerland. On the same day, he flew to Helsinki, where he checked in at the Hotel Torni, room 309, then moved to Hotel Klaus Kurki, room 429.[50] He was issued a Soviet visa on October 14. Oswald left Helsinki by train on the following day, crossed the Soviet border at Vainikkala, and arrived in Moscow on October 16.[51] His visa, valid only for a week, was due to expire on October 21.[52] During his stay in the Soviet Union his mail was intercepted and read by the CIA, with Reuben Efron being charged with this assignment.[53]

Almost immediately after arriving, Oswald informed his Intourist guide of his desire to become a Soviet citizen. When asked why by the various Soviet officials he encountered – all of whom, by Oswald's account, found his wish incomprehensible – he said that he was a communist, and gave what he described in his diary as "vauge [sic] answers about 'Great Soviet Union'".[52] On October 21, the day his visa was due to expire, he was told that his citizenship application had been refused, and that he had to leave the Soviet Union that evening. Distraught, Oswald inflicted a minor but bloody wound to his left wrist in his hotel room bathtub soon before his Intourist guide was due to arrive to escort him from the country, according to his diary because he wished to kill himself in a way that would shock her.[52] Delaying Oswald's departure because of his self-inflicted injury, the Soviets kept him in a Moscow hospital under psychiatric observation for a week, until October 28, 1959.[54]

According to Oswald, he met with four more Soviet officials that day, who asked if he wanted to return to the United States. Oswald replied by insisting that he wanted to live in the Soviet Union as a Soviet national. When pressed for identification papers, he provided his Marine Corps discharge papers.[55]

On October 31, Oswald appeared at the United States embassy in Moscow and declared a desire to renounce his U.S. citizenship.[56][57] "I have made up my mind", he said; "I'm through."[58] He told the U.S. embassy interviewing officer, Richard Edward Snyder, that "he had been a radar operator in the Marine Corps and that he had voluntarily stated to unnamed Soviet officials that as a Soviet citizen he would make known to them such information concerning the Marine Corps and his specialty as he possessed. He intimated that he might know something of special interest."[59] Such statements led to Oswald's hardship/honorable military reserve discharge being changed to undesirable.[60] The story of the defection of a former U.S. Marine to the Soviet Union was reported by both the Associated Press and United Press International.[61][62]

Though Oswald had wanted to attend Moscow State University, in January 1960 he was sent to Minsk, Belarus, to work as a lathe operator at the Gorizont Electronics Factory, which produced radios, televisions, and military and space electronics.[63] Stanislau Shushkevich, who later became independent Belarus's first head of state, also worked at Gorizont at the time, and was assigned to help Oswald improve his Russian.[64] Oswald received a government-subsidized, fully furnished studio apartment in a prestigious building and an additional supplement to his factory pay, which allowed him to have a comfortable standard of living by working-class Soviet standards,[65] though he was kept under constant surveillance.[66]

From mid-1960 to early 1961, Oswald was in a relationship with Ella German (Belarusian: Эла Герман), a Belarusian coworker born in 1937.[67][10][68] They ate together in the factory cafeteria every day and dated about twice each week.[69] German later described Oswald as "a pleasant-looking guy with a good sense of humor ... not as rough and rude as the men here were back then";[70] she did not love him, but thought he was lonely and continued to date him out of pity.[71] Their relationship became more serious – in Oswald's eyes – during the summer and fall of 1960,[68] but began to deteriorate after German learned in October that Oswald had been seeing other women.[68] On January 2, 1961, Oswald proposed, but German refused.[68][72]

Return to the U.S.

Oswald wrote in his diary in January 1961: "I am starting to reconsider my desire about staying. The work is drab, the money I get has nowhere to be spent. No nightclubs or bowling alleys, no places of recreation except the trade union dances. I have had enough."[73] Shortly afterwards, Oswald (who had never formally renounced his U.S. citizenship) wrote to the Embassy of the United States, Moscow requesting the return of his American passport, and proposing to return to the U.S. if any charges against him would be dropped.[74]

In March 1961, Oswald met Marina Prusakova (born 1941), a 19-year-old pharmacology student; they married six weeks later.[n 4][75] The Oswalds' first child, June, was born on February 15, 1962. On May 24, 1962, Oswald and Marina applied at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow for documents that enabled her to immigrate to the U.S. On June 1, the U.S. Embassy gave Oswald a repatriation loan of $435.71.[76] Oswald, Marina, and their infant daughter left for the United States, where they received less attention from the press than Oswald expected.[77] According to the Warren Report, Oswald and his wife returned to America on 13 June, they arrived onboard the Maasdam and landed at Hoboken in New Jersey. Here they were met by Spas T. Raikin of the Travelers Aid Society who had been contacted by the US Department of State.[78]

Dallas–Fort Worth

The Oswalds soon settled in the Dallas/Fort Worth area, where Lee's mother and brother lived. Lee began a manuscript on Soviet life, though he eventually gave up the project.[79] The Oswalds also became acquainted with a number of anti-Communist Russian and East European émigrés in the area.[80][81] In testimony to the Warren Commission, Alexander Kleinlerer said that the Russian émigrés sympathized with Marina, while merely tolerating Oswald, whom they regarded as rude and arrogant.[n 5]

Although the Russian émigrés eventually abandoned Marina when she made no sign of leaving her husband,[82] Oswald found an unlikely friend in 51-year-old Russian émigré George de Mohrenschildt, a well-educated petroleum geologist with international business connections.[83][84] A native of Russia, Mohrenschildt later told the Warren Commission that Oswald had a "remarkable fluency in Russian".[85] Marina, meanwhile, befriended Ruth Paine,[86] a Quaker trying to learn Russian, and her husband Michael Paine, who worked for Bell Helicopter.[87]

In July 1962, Oswald was hired by the Leslie Welding Company as a sheet metal worker in Dallas; he disliked the work and quit after three months. On October 12, he started working for the graphic-arts firm of Jaggars-Chiles-Stovall as a photoprint trainee. A fellow employee at Jaggars-Chiles-Stovall testified that Oswald's rudeness at his new job was such that fights threatened to break out, and that he once saw Oswald reading a Russian-language publication.[88][n 6] Oswald was fired in the first week of April 1963.[89]

Edwin Walker assassination attempt

In March 1963, Oswald used the alias "A. Hidell" to make a mail-order purchase of a secondhand 6.5 mm caliber Carcano rifle for $19.95, plus $1.50 for shipping.[90] He also purchased a .38 Smith & Wesson Model 10 revolver by mail for $29.95 plus $1.27 shipping.[91] The Warren Commission concluded that Oswald attempted to kill retired U.S. Major General Edwin Walker on April 10, 1963, and that Oswald fired the Carcano rifle at Walker through a window from less than 100 feet (30 m) away as Walker sat at a desk in his Dallas home. The bullet struck the window-frame and Walker's only injuries were bullet fragments to the forearm.[92] The United States House Select Committee on Assassinations stated that the "evidence strongly suggested" that Oswald carried out the shooting.[93]

General Walker was an outspoken anti-communist, segregationist, and member of the John Birch Society. In 1961, Walker had been relieved of his command of the 24th Division of the U.S. Army in West Germany for distributing right-wing literature to his troops.[94][95] Walker's later actions in opposition to racial integration at the University of Mississippi led to his arrest on insurrection, seditious conspiracy, and other charges. He was temporarily held in a mental institution on orders from President Kennedy's brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, but a grand jury declined to indict him.[96]

Marina Oswald testified that her husband told her that he traveled by bus to General Walker's house and shot at Walker with his rifle.[97][98] She said that Oswald considered Walker to be the leader of a "fascist organization".[99] A note Oswald left for Marina on the night of the attempt, telling her what to do if he did not return, was found ten days after the Kennedy assassination.[100][101][102][103]

Before the Kennedy assassination, Dallas police had no suspects in the Walker shooting,[104] but Oswald's involvement was suspected within hours of his arrest following the assassination.[105] The Walker bullet was too damaged to run conclusive ballistics studies on it,[106] but neutron activation analysis later showed that it was "extremely likely" that it was made by the same manufacturer and for the same rifle make as the two bullets which later struck Kennedy.[n 7]

George de Mohrenschildt testified that he "knew that Oswald disliked General Walker".[107] Regarding this, de Mohrenschildt and his wife Jeanne recalled an incident that occurred the weekend following the Walker assassination attempt. The de Mohrenschildts testified that on April 14, 1963, just before Easter Sunday, they were visiting the Oswalds at their new apartment and had brought them a toy Easter bunny to give to their child. As Oswald's wife Marina was showing Jeanne around the apartment, they discovered Oswald's rifle standing upright, leaning against the wall inside a closet. Jeanne told George that Oswald had a rifle, and George joked to Oswald, "Were you the one who took a pot-shot at General Walker?" When asked about Oswald's reaction to this question, George de Mohrenschildt told the Warren Commission that Oswald "smiled at that".[108] When de Mohrenschildt's wife Jeanne was asked about Oswald's reaction, she said, "I didn't notice anything"; she continued, "we started laughing our heads off, big joke, big George's joke".[109] Jeanne de Mohrenschildt testified that this was the last time she or her husband ever saw the Oswalds.[110][111]

New Orleans

Oswald returned to New Orleans on April 24, 1963.[112] Marina's friend Ruth Paine drove her by car from Dallas to join Oswald in New Orleans the following month.[113] On May 10, Oswald was hired by the Reily Coffee Company as a machinery greaser.[114] He was fired in July "because his work was not satisfactory and because he spent too much time loitering in Adrian Alba's garage next door, where he read rifle and hunting magazines".[115]

In his 1988 book On the Trail of the Assassins, New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison claimed that Oswald really spent that time across the street at 544 Camp Street. These were the law offices of Guy Banister, a former FBI agent, an avid segregationist, and a local politician. Garrison added that Guy Banister, during the summer of 1963 in New Orleans, was most interested in infiltrating the Fair Play for Cuba Committee, and used Oswald as his spy.[116] In their 1978 investigation, the House Select Committee on Assassinations investigated a possible connection between Oswald and Banister at the Camp Street address. The HSCA wrote that it "could find no documentary proof that Banister had a file on Lee Harvey Oswald nor could the committee find credible witnesses whoever saw Lee Harvey Oswald and Guy Banister together. There are indications, however, that Banister at least knew of Oswald's leafletting activities and probably maintained a file on him."[117]

On May 26, Oswald wrote to the New York City headquarters of the pro-Fidel Castro Fair Play for Cuba Committee, proposing to rent "a small office at my own expense for the purpose of forming a FPCC branch here in New Orleans".[118] Three days later, the FPCC responded to Oswald's letter advising against opening a New Orleans office "at least not ... at the very beginning".[119] In a follow-up letter, Oswald replied, "Against your advice, I have decided to take an office from the very beginning."[120]

On May 29, Oswald ordered the following items from a local printer: 500 application forms, 300 membership cards, and 1,000 leaflets with the heading, "Hands Off Cuba".[121] According to Marina, Lee told her to sign the name "A.J. Hidell" as chapter president on his membership card.[122]

According to anti-Castro militant Carlos Bringuier, Oswald visited him on August 5 and 6 at a store he owned in New Orleans. Bringuier was the New Orleans delegate for the anti-Castro organization Directorio Revolucionario Estudantil (DRE). Bringuier would later tell the Warren Commission that he believed Oswald's visits were an attempt by Oswald to infiltrate his group.[123] On August 9, Oswald turned up in downtown New Orleans handing out pro-Castro leaflets. Bringuier confronted Oswald, claiming he was tipped off about Oswald's leafleting by a friend. A scuffle ensued and Oswald, Bringuier, and two of Bringuier's friends were arrested for disturbing the peace.[124][125] Prior to leaving the police station, Oswald requested to speak with an FBI agent.[126] Oswald told the agent that he was a member of the New Orleans branch of the Fair Play for Cuba Committee which he claimed had 35 members and was led by A. J. Hidell.[126] In fact, Oswald was the branch's only member and it had never been chartered by the national organization.[127]

A week later, on August 16, Oswald again passed out Fair Play for Cuba leaflets with two hired helpers, this time in front of the International Trade Mart. The incident was filmed by WDSU-TV.[128][129] The next day, Oswald was interviewed by WDSU radio commentator William Stuckey, who probed Oswald's background.[130][131] A few days later, Oswald accepted Stuckey's invitation to take part in a radio debate with Carlos Bringuier and Bringuier's associate Edward Scannell Butler, head of the right-wing Information Council of the Americas (INCA).[130][132][133]

Mexico

Marina's friend Ruth Paine transported Marina and her child by car from New Orleans to the Paine home in Irving, Texas, near Dallas, on September 23, 1963.[113][134] Oswald stayed in New Orleans at least two more days to collect a $33 unemployment check. It is uncertain when he left New Orleans; he is next known to have boarded a bus in Houston on September 26 – bound for the Mexican border, rather than Dallas – and to have told other bus passengers that he planned to travel to Cuba via Mexico.[135][136] He arrived in Mexico City on September 27, where he applied for a transit visa at the Cuban consulate,[137] claiming he wanted to visit Cuba on his way to the Soviet Union. The Cuban consular officials insisted Oswald would need Soviet approval, but he was unable to get prompt co-operation from the Soviet consulate. CIA documents note Oswald spoke "terrible hardly recognizable Russian" during his meetings with Cuban and Soviet officials.[138]

After five days of shuttling between consulates – and including a heated argument with an official at the Cuban consulate, impassioned pleas to KGB agents, and at least some CIA scrutiny[139] – Oswald was told by a Cuban consular officer that he was disinclined to approve the visa, saying "a person like [Oswald] in place of aiding the Cuban Revolution, was doing it harm".[140] Later, on October 18, the Cuban embassy approved the visa, but by this time Oswald was back in the United States and had given up on his plans to visit Cuba and the Soviet Union. Still later, eleven days before the assassination of President Kennedy, Oswald wrote to the Soviet embassy in Washington, D.C., saying, "Had I been able to reach the Soviet Embassy in Havana, as planned, the embassy there would have had time to complete our business."[141][142]

While the Warren Commission concluded that Oswald had visited Mexico City and the Cuban and Soviet consulates, questions regarding whether someone posing as Oswald had appeared at the embassies were serious enough to be investigated by the House Select Committee on Assassinations. Later, the Committee agreed with the Warren Commission that Oswald had visited Mexico City and concluded that "the majority of evidence tends to indicate" that Oswald visited the consulates, but the Committee could not rule out the possibility that someone else had used his name in visiting the consulates.[143]

According to a CIA document released in 2017, it is possible Oswald was trying to get the necessary documents from the embassies to make a quick escape to the Soviet Union after the assassination.[138]

Return to Dallas

On October 2, 1963, Oswald left Mexico City by bus and arrived in Dallas the next day. Ruth Paine said that a neighbor told her on October 14 about a job opening at the Texas School Book Depository, where her neighbor's brother, Wesley Frazier, worked. Mrs. Paine informed Oswald, who was interviewed at the depository and was hired there on October 16 as a $1.25 an hour minimum wage order filler.[144] Oswald's supervisor, Roy S. Truly (1907–1985), said that Oswald "did a good day's work" and was an above-average employee.[145][146] During the week, Oswald stayed in a Dallas rooming house under the name "O. H. Lee",[147] but he spent his weekends with Marina at the Paine home in Irving. Oswald did not drive a car, but he commuted to and from Dallas on Mondays and Fridays with his co-worker Wesley Frazier. On October 20 (a month before the assassination), the Oswalds' second daughter, Audrey, was born.[148][149]

The Dallas branch of the FBI became interested in Oswald after its agent learned that the CIA had determined that Oswald had been in contact with the Soviet embassy in Mexico, making Oswald a possible espionage case.[150] FBI agents twice visited the Paine home in early November, when Oswald was not present, and spoke to Mrs. Paine.[151] Oswald visited the Dallas FBI office about two to three weeks before the assassination, asking to see Special Agent James P. Hosty. When he was told that Hosty was unavailable, Oswald left a note that, according to the receptionist, read: "Let this be a warning. I will blow up the FBI and the Dallas Police Department if you don't stop bothering my wife" [signed] "Lee Harvey Oswald". The note allegedly contained a threat, but accounts vary as to whether Oswald threatened to "blow up the FBI" or merely "report this to higher authorities". According to Hosty, the note said, "If you have anything you want to learn about me, come talk to me directly. If you don't cease bothering my wife, I will take the appropriate action and report this to the proper authorities." Agent Hosty said that he destroyed Oswald's note on orders from his superior, Gordon Shanklin, after Oswald was named the suspect in the Kennedy assassination.[152][153]

John F. Kennedy and J. D. Tippit shootings

In the days before Kennedy's arrival, several local newspapers published the route of Kennedy's motorcade, which passed the Texas School Book Depository.[154] On Thursday, November 21, 1963, Oswald asked Frazier for an unusual mid-week lift back to Irving, saying he had to pick up some curtain rods. The next morning (the day of the assassination), he returned to Dallas with Frazier. He left $170 and his wedding ring,[155] but took a large paper bag with him. Frazier reported that Oswald told him the bag contained curtain rods.[156][157] The Warren Commission concluded that the package of "curtain rods" actually contained the rifle that Oswald was going to use for the assassination.[158]

One of Oswald's co-workers, Charles Givens, testified to the Commission that he last saw Oswald on the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository (TSBD) at approximately 11:55 a.m., which was 35 minutes before the motorcade entered Dealey Plaza.[n 8] The Commission report stated that Oswald was not seen again "until after the shooting".[159] In an FBI report taken the day after the assassination, Givens said that the encounter took place at 11:30 a.m. and that he saw Oswald reading a newspaper in the first-floor domino room at 11:50 a.m, 20 minutes later.[160][161] William Shelley, a foreman at the depository, also testified that he saw Oswald near the telephone on the first floor between 11:45 and 11:50 a.m.[162] Janitor Eddie Piper also testified that he spoke to Oswald on the first floor at 12:00 p.m.[163] Another co-worker, Bonnie Ray Williams, was eating his lunch on the sixth floor of the depository and was there until at least 12:10 p.m.[164] He said that during that time, he did not see Oswald, or anyone else, on the sixth floor and thought that he was the only person up there.[165] He also said that some boxes in the southeast corner may have prevented him from seeing deep into the "sniper's nest".[166] Various workers – including Givens, Junior Jarman, Troy West, Danny Arce, Jack Dougherty, Joe Molina, Mrs. Robert Reid, and Bill Lovelady – who were either in the first or second floor lunchrooms at times between 12:00 and 12:30 pm reported that Oswald was not present in those rooms during their lunch breaks.[167][n 9]

As Kennedy's motorcade passed through Dealey Plaza at approximately 12:30 p.m. on November 22, Oswald fired three rifle shots from the southeast-corner window on the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository,[168] killing the President and seriously wounding Texas Governor John Connally. One shot apparently missed the presidential limousine entirely, another struck both Kennedy and Connally, and a third bullet struck Kennedy in the head,[169] killing him. Bystander James Tague received a minor facial injury from a small piece of curbstone that had fragmented after it was struck by one of the bullets.

Witness Howard Brennan was sitting across the street from the Texas School Book Depository and watching the motorcade go by. He notified police that he heard a shot come from above and looked up to see a man with a rifle fire another shot from the southeast corner window on the sixth floor. He said he had seen the same man minutes earlier looking through the window.[170] Brennan gave a description of the shooter,[171] and Dallas police subsequently broadcast descriptions at 12:45 p.m., 12:48 p.m., and 12:55 p.m.[172] After the second shot was fired, Brennan recalled, "This man I saw previous[ly] was aiming for his last shot ... and maybe paused for another second as though to assure himself that he had hit his mark."[173]

The paper bag Frazier had described was found by police near the open sixth-floor window from which Oswald was determined to have fired;[157] it was 38 inches (97 cm) long and had marks on its inside consistent with having been used to carry a rifle.[157] Three shell casings were found on the floor near the window, and a Mannlicher-Carcano rifle with telescopic sight was found on the northwest corner of the sixth-floor near the staircase.[174][175][176]

According to the investigations, after the shooting Oswald covered the rifle with boxes and descended via the rear stairwell. About 90 seconds after the shots sounded, he was encountered in the second-floor lunchroom by Dallas police officer Marrion L. Baker, who was with Oswald's supervisor, Roy Truly. Baker let Oswald pass after Truly identified him as an employee. Baker later said Oswald did not seem "nervous" or "out of breath".[177] Truly said that Oswald looked "startled" when Baker pointed his gun directly at him.[178][179] Mrs. Robert Reid, a clerical supervisor at the depository who returned to her office within two minutes of the shooting, said she saw Oswald, "very calm", on the second floor holding a Coca-Cola bottle.[180] As they walked past each other, Mrs. Reid said to Oswald, "The President has been shot" to which he mumbled something in response, but Reid did not understand him.[181] Oswald was believed to have left the depository through the front entrance just before police sealed it off. Truly later pointed out to officers that Oswald was the only employee that he was certain was missing.[182][183]

At about 12:40 p.m., 10 minutes after the shooting, Oswald boarded a city bus. Probably due to heavy traffic, he requested a transfer from the driver and got off two blocks later.[184] Oswald then took a taxicab to his rooming house at 1026 North Beckley Avenue and entered through the front door at about 1:00 p.m. According to his housekeeper Earlene Roberts, Oswald immediately went to his room, "walking pretty fast".[185] Roberts said that Oswald left "a very few minutes" later, zipping up a jacket he was not wearing when he had entered earlier. As Oswald left, Roberts looked out of the window of her house and last saw him standing at the northbound Beckley Avenue bus stop in front of her house.[186][187]

The Warren Commission concluded that at approximately 1:15 p.m., Dallas Patrolman J. D. Tippit drove up in his patrol car alongside Oswald, presumably because Oswald resembled the broadcast description of the man seen by witness Howard Brennan firing shots at Kennedy's motorcade. He encountered Oswald near the corner of East 10th Street and North Patton Avenue.[188][189] This location is about nine-tenths of a mile (1.4 km) southeast of Oswald's rooming house – a distance that the Warren Commission concluded "Oswald could have easily walked".[190] Tippit pulled alongside Oswald and "apparently exchanged words with [him] through the right front or vent window".[191] "Shortly after 1:15 p.m.",[n 10] Tippit exited his car. Oswald immediately fired his pistol and killed the policeman with four shots.[191][192] Numerous witnesses heard the shots and saw Oswald flee the scene holding a revolver; nine positively identified him as the man who shot Tippit and fled.[193][n 11] Four cartridge cases found at the scene were identified by expert witnesses[194] before the Warren Commission and the House Select Committee as having been fired from the revolver later found in Oswald's possession, excluding all other weapons. The bullets taken from Tippit's body could not be positively identified as having been fired from Oswald's revolver, as the bullets were too extensively damaged to make conclusive assessments.[194][195]

Arrest at the Texas Theatre

Shoe store manager Johnny Brewer testified that he saw Oswald "ducking into" the entrance alcove of his store. Suspicious of this activity, Brewer watched Oswald continue up the street and slip without paying into the nearby Texas Theatre, where the film War Is Hell was playing.[196] He alerted the theater's ticket clerk, who telephoned police[197] at about 1:40 p.m.

As police arrived, the house lights were brought up and Brewer pointed out Oswald sitting near the rear of the theater. Police Officer Nick McDonald testified that he was the first to reach Oswald and that Oswald seemed ready to surrender saying, "Well, it is all over now." McDonald said that Oswald pulled out a pistol tucked into the front of his pants, then pointed the pistol at him, and pulled the trigger. McDonald stated that the pistol did not fire because the pistol's hammer came down on the webbing between the thumb and index finger of his hand as he grabbed for the pistol. McDonald also said that Oswald struck him, but that he struck back and Oswald was disarmed.[198][199] As he was led from the theater, Oswald shouted he was a victim of police brutality.[200]

Oswald was formally arraigned for the murder of Officer Tippit at 7:10 p.m.[201][202]

Soon after his arrest, Oswald encountered reporters in a hallway. Oswald declared, "I didn't shoot anybody" and, "They've taken me in because of the fact that I lived in the Soviet Union. I'm just a patsy!"[203] Later, at an arranged press meeting, a reporter asked, "Did you kill the President?" and Oswald – who by that time had been advised of the charge of murdering Tippit, but had not yet been arraigned in Kennedy's death – answered, "No, I have not been charged with that. In fact, nobody has said that to me yet. The first thing I heard about it was when the newspaper reporters in the hall asked me that question."[204] As he was led from the room the question was called out, "What did you do in Russia?" and, "How did you hurt your eye?"; Oswald answered, "A policeman hit me."[201] By early the next morning (shortly after 1:30 a.m.) he had been arraigned for the assassination of President Kennedy.[205]

Police interrogation

Oswald was interrogated several times during his two days at Dallas Police Headquarters. He admitted that he went to his rooming house after leaving the book depository. He also admitted that he changed his clothes and armed himself with a .38 caliber revolver before leaving his house to go to the theater.[209] Oswald denied killing Kennedy and Tippit, denied owning a rifle, and said two photographs of him holding a rifle and a pistol were fakes. He denied telling his co-worker he wanted a ride to Irving to get curtain rods for his apartment (he said that the package contained his lunch). He also denied carrying a long, bulky package to work the morning of the assassination. Oswald denied knowing an "A. J. Hidell". Oswald was then shown a forged Selective Service System card bearing his photograph and the alias, "Alek James Hidell" that he had in his possession at the time of his arrest. Oswald refused to answer any questions concerning the card, saying "you have the card yourself and you know as much about it as I do".[210][211]

FBI Special Agent James P. Hosty and Dallas Police Captain Will Fritz (chief of homicide) conducted the first interrogation of Oswald on Friday, November 22. When Oswald was asked to account for himself at the time of the assassination, he replied that he was eating his lunch in the first-floor lounge (known as the "domino room"). He said that he then went to the second-floor lunchroom to buy a Coca-Cola from the soda machine there and was drinking it when he encountered Dallas motorcycle policeman Marrion L. Baker, who had entered the building with his gun drawn.[212][213][214][215] Oswald said that while he was in the domino room, he saw two "Negro employees" walking by, one he recognized as "Junior" and a shorter man whose name he could not recall.[216] Junior Jarman and Harold Norman confirmed to the Warren Commission that they had "walked through" the domino room around noon during their lunch break. When asked if anyone else was in the domino room, Norman testified that somebody else was there, but he could not remember who it was. Jarman testified that Oswald was not in the domino room when he was there.[217][218]

When homicide detective Jim Leavelle testified before the Warren Commission, he said that the first time he had ever sat in on an interrogation with Oswald was on Sunday morning, November 24, 1963. When Counsel Joseph Ball asked Leavelle if he had ever spoken to Oswald before this interrogation, he stated, "No, I had never talked to him before". Leavelle then stated during his testimony that "the only time I had connections with Oswald was this Sunday morning [November 24, 1963]. I never had [the] occasion... to talk with him at any time..."[219] During Oswald's last interrogation on November 24, according to postal inspector Harry Holmes, Oswald was again asked where he was at the time of the shooting. Holmes (who attended the interrogation at the invitation of Captain Will Fritz) said that Oswald replied that he was working on an upper floor when the shooting occurred, then went downstairs where he encountered Dallas motorcycle policeman Marrion L. Baker.[220]

Oswald asked for legal representation several times during the interrogation, and he also asked for assistance during encounters with reporters. When H. Louis Nichols, President of the Dallas Bar Association, met with him in his cell on Saturday, he declined their services, saying he wanted to be represented by John Abt, chief counsel to the Communist Party USA, or by lawyers associated with the American Civil Liberties Union.[221][222] Both Oswald and Ruth Paine tried to reach Abt by telephone several times Saturday and Sunday,[223][224] but Abt was away for the weekend.[225] Oswald also declined his brother Robert's offer on Saturday to obtain a local attorney.[226]

During an interrogation with Captain Fritz, when asked, "Are you a communist?", he replied, "No, I am not a communist. I am a Marxist."[227][228][229]

Murder

| Murder of Lee Harvey Oswald | |

|---|---|

Ruby shooting Oswald, who is being escorted by Dallas police. Detective Jim Leavelle is wearing the tan suit. | |

| Location | Dallas, Texas, U.S. |

| Date | November 24, 1963 11:21 a.m. (CST) |

| Target | Lee Harvey Oswald |

Attack type | Murder by shooting |

| Weapon | .38 caliber Colt Cobra revolver |

| Deaths | 1 (Lee Harvey Oswald) |

| Perpetrator | Jack Ruby |

| Motive | Disputed |

| Verdict | Guilty |

| Convictions | Murder with malice

|

| Sentence | Death (overturned) |

On Sunday, November 24, detectives were escorting Oswald through the basement of Dallas Police Headquarters toward an armored car that was to take him from the city jail (located on the fourth floor of police headquarters) to the nearby county jail. At 11:21 a.m. CST, Dallas nightclub operator Jack Ruby approached Oswald from the side of the crowd and shot him once in the abdomen at close range.[230] As the shot rang out, a police detective recognized Ruby and exclaimed: "Jack, you son of a bitch!"[231] The crowd outside the headquarters applauded when they heard that Oswald had been shot.[232]

An unconscious Oswald was taken by ambulance to Parkland Memorial Hospital – the same hospital where Kennedy was pronounced dead two days earlier. Oswald died at 1:07 p.m;[147] Dallas police chief Jesse Curry announced his death on a TV news broadcast.[citation needed]

At 2:45 p.m. the same day, an autopsy was performed on Oswald in the Office of the County Medical Examiner.[230] Dallas County medical examiner Earl Rose announced the results of the gross autopsy: "The two things that we could determine were, first, that he died from a hemorrhage from a gunshot wound, and that otherwise he was a physically healthy male."[233] Rose's examination found that the bullet entered Oswald's left side in the front part of the abdomen and caused damage to his spleen, stomach, aorta, vena cava, kidney, liver, diaphragm, and eleventh rib before coming to rest on his right side.[233]

A network television pool camera was broadcasting live to cover the transfer; millions of people watching on NBC saw the shooting as it happened, and on other networks within minutes afterward.[234] In 1964, Robert H. Jackson of the Dallas Times Herald was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Photography for his photograph taken immediately after the shot was fired, as Oswald began to double over in pain.[235]

Ruby's motive

Ruby later said he had been distraught over Kennedy's death and that his motive for killing Oswald was "saving Mrs. Kennedy the discomfiture of coming back to trial".[236] Others have hypothesized that Ruby was part of a conspiracy. G. Robert Blakey, chief counsel for the House Select Committee on Assassinations from 1977 to 1979, said: "The most plausible explanation for the murder of Oswald by Jack Ruby was that Ruby had stalked him on behalf of organized crime, trying to reach him on at least three occasions in the forty-eight hours before he silenced him forever."[237]

Burial

Miller Funeral Home had great difficulty finding a cemetery willing to accept Oswald's remains; Rose Hill Cemetery in Fort Worth eventually agreed. A Lutheran minister reluctantly agreed to officiate but then failed to appear. Reverend Louis Saunders of the Fort Worth Council of Churches volunteered, saying that "someone had to help this family". He performed a brief graveside service under heavy guard on November 25. Reporters covering the burial were asked to act as pallbearers.[238][239][240]

Oswald's original tombstone, which gave his full name, birth date, and death date, was stolen four years after the assassination, and his mother replaced it with a marker simply inscribed Oswald.[241] His mother's body was buried beside his in 1981.[242]

A claim that a look-alike Russian agent was buried in place of Oswald led to the body's exhumation on October 4, 1981.[243] Dental records confirmed it was Oswald. The remains were reburied in a new coffin because of water damage to the original.[244]

In 2010, Miller Funeral Home employed a Los Angeles auction house to sell the original coffin to an anonymous bidder for $87,468.[243][244] The sale was halted after Oswald's brother Robert (1934–2017)[245] sued to reclaim the coffin.[243][244] In 2015, a district judge in Tarrant County, Texas, ruled that the funeral home intentionally concealed the existence of the coffin from Robert Oswald, who had originally purchased it and believed that it had been discarded after the exhumation,[243][244] and ordered it returned to Robert Oswald along with damages equal to the sale price.[243][244] Robert Oswald's attorney stated that the coffin would likely be destroyed "as soon as possible".[243][244]

Official investigations

Warren Commission

President Lyndon B. Johnson issued an executive order that created the Warren Commission to investigate the assassination. The commission concluded that Oswald acted alone in assassinating Kennedy, and the Warren Report could not ascribe any one motive or group of motives to Oswald's actions:

It is apparent, however, that Oswald was moved by an overriding hostility to his environment. He does not appear to have been able to establish meaningful relationships with other people. He was perpetually discontented with the world around him. Long before the assassination he expressed his hatred for American society and acted in protest against it. Oswald's search for what he conceived to be the perfect society was doomed from the start. He sought for himself a place in history – a role as the "great man" who would be recognized as having been in advance of his times. His commitment to Marxism and communism appears to have been another important factor in his motivation. He also had demonstrated a capacity to act decisively and without regard to the consequences when such action would further his aims of the moment. Out of these and the many other factors which may have molded the character of Lee Harvey Oswald there emerged a man capable of assassinating President Kennedy.[246]

The proceedings of the commission were closed, though not secret. Approximately three percent of its files have yet to be released to the public, which has continued to provoke speculation among researchers.[n 12]

Ramsey Clark Panel

In 1968, the Ramsey Clark Panel examined various photographs, X-ray films, documents, and other evidence. It concluded that Kennedy was struck by two bullets fired from above and behind him: one of which traversed the base of the neck on the right side without striking bone, and the other of which entered the skull from behind and destroyed its right side.[247]

House Select Committee

In 1979, after a review of the evidence and of prior investigations, the United States House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) largely concurred with the Warren Commission and was preparing to issue a finding that Oswald had acted alone in killing Kennedy.[248] Late in the Committee's proceedings, a dictabelt recording was introduced, purportedly recording sounds heard in Dealey Plaza before, during, and after the shots. After an analysis by the firm Bolt, Beranek and Newman appeared to indicate more than three gunshots, the HSCA revised its findings to assert a "high probability that two gunmen fired" at Kennedy and that Kennedy "was probably assassinated as the result of a conspiracy". Although the Committee was "unable to identify the other gunman or the extent of the conspiracy", it made a number of further findings regarding the likelihood that particular groups, named in the findings, were involved.[249] Four of the twelve members of the HSCA dissented from this conclusion.[248]

The acoustic evidence has since been discredited.[250][251][252][253][254][255] Officer H.B. McLain, from whose motorcycle radio the HSCA acoustic experts said the Dictabelt evidence came,[256][257] has repeatedly stated that he was not yet in Dealey Plaza at the time of the assassination.[258] McLain asked the Committee, "'If it was my radio on my motorcycle, why did it not record the revving up at high speed plus my siren when we immediately took off for Parkland Hospital?'"[259]

In 1982, a panel of twelve scientists appointed by the National Academy of Sciences, including Nobel laureates Norman Ramsey and Luis Alvarez, unanimously concluded that the acoustic evidence submitted to the HSCA was "seriously flawed", was recorded after the shots, and did not indicate additional gunshots.[260] Their conclusions were published in the journal Science.[261]

In a 2001 article in the journal Science & Justice, D.B. Thomas wrote that the NAS investigation was itself flawed. He concluded with a 96.3 percent certainty that at least two gunmen fired at President Kennedy and that at least one shot came from the grassy knoll.[262] In 2005, Thomas's conclusions were rebutted in the same journal. Ralph Linsker and several members of the original NAS team reanalyzed the timings of the recordings and reaffirmed the earlier conclusion of the NAS report that the alleged shot sounds were recorded approximately one minute after the assassination.[263] In 2010, D.B. Thomas challenged the 2005 Science & Justice article and restated his conclusion that there were at least two gunmen.[264]

Backyard photos

Photos of Oswald holding the rifle that was later determined to be the murder weapon are an important piece of evidence linking Oswald to the crime. The photos were uncovered with other possessions belonging to Oswald in the garage of Ruth Paine in Irving, Texas, on November 23, 1963.[265] Marina Oswald told the Warren Commission that around March 31, 1963, she had taken pictures of Oswald as he posed with a Carcano rifle, a holstered pistol, and two Marxist newspapers – The Militant and The Worker.[266]

Oswald had sent one of the photos to The Militant's New York office with an accompanying letter stating he was "prepared for anything": according to Sylvia Weinstein, who handled the newspaper's subscriptions at the time, Oswald was seen as "kookie" and politically "dumb and totally naive", as he apparently did not know that The Militant, published by the Trotskyist Socialist Workers Party, and The Worker, published by the pro-Soviet Communist Party USA, were rival publications and ideologically opposed to each other.[267]

The pictures were shown to Oswald after his arrest, but he insisted that they were forgeries.[265]

In 1964, Marina testified before the Warren Commission that she had photographed Oswald, at his request and using his camera.[268] These photos were labelled CE 133-A and CE 133-B. CE 133-A shows the rifle in Oswald's left hand and newspapers in front of his chest in the other, while the rifle is held with the right hand in CE 133-B. The Carcano in the images had markings matching those on the rifle found in the Book Depository after the assassination. Oswald's mother testified that on the day after the assassination she and Marina destroyed another photograph with Oswald holding the rifle with both hands over his head, with "To my daughter June" written on it.[269]

When shown one of the photos during his interrogation by Dallas police, Oswald stated that it was a fake. According to Dallas Police Captain Will Fritz:

He said that the picture was not his, that the face was his face, but that this picture had been made by someone superimposing his face, the other part of the picture was not him at all and that he had never seen the picture before. ... He told me that he understood photography real well, and that in time, he would be able to show that it was not his picture, and that it had been made by someone else.[270]

The HSCA obtained another first-generation print (from CE 133-A) on April 1, 1977, from the widow of George de Mohrenschildt. The words "Hunter of fascists – ha ha ha!" written in block Russian were on the back. Also in English were added in script: "To my friend George, Lee Oswald, 5/IV/63 [April 5, 1963]."[271] Handwriting experts for the HSCA concluded the English inscription and signature were by Oswald. After two original photos, one negative and one first-generation copy had been found, the Senate Intelligence Committee located (in 1976) a third backyard photo (CE 133-C) showing Oswald with newspapers held away from his body in his right hand.

These photos, widely recognized as some of the most significant evidence against Oswald, have been subjected to rigorous analysis.[272] Photographic experts consulted by the HSCA concluded they were genuine,[273] answering twenty-one points raised by critics.[274] Marina Oswald has always maintained she took the photos herself, and the 1963 de Mohrenschildt print bearing Oswald's signature clearly indicate they existed before the assassination. Nonetheless, some continue to contest their authenticity.[275] In 2009, after digitally analyzing the photograph of Oswald holding the rifle and paper, computer scientist Hany Farid concluded[276] that the photo "almost certainly was not altered".[277]

Other investigations and dissenting theories

Some critics have not accepted the conclusions of the Warren Commission and have proposed several other theories, such as that Oswald conspired with others, or was not involved at all and was framed. A Gallup Poll taken in mid-November 2013, showed 61% believed that Kennedy was killed as a result of conspiracy, and only 30% thought Oswald acted alone.[278]

Oswald was never prosecuted because he was murdered two days after the assassination. In March 1967, New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison arrested and charged New Orleans businessman Clay Shaw with conspiring to assassinate President Kennedy, with the help of Oswald, David Ferrie, and others. Garrison believed that the men were part of an arms smuggling ring supplying weapons to the anti-Castro Cubans in a conspiracy with elements of the CIA to kill Kennedy.[116] The trial of Clay Shaw began in January 1969 in Orleans Parish Criminal Court. The jury acquitted Shaw.

Several films have fictionalized a trial of Oswald, depicting what may have happened had Ruby not killed Oswald. The Trial of Lee Harvey Oswald (1964); The Trial of Lee Harvey Oswald (1977); and On Trial: Lee Harvey Oswald (1986) have imagined such a trial. In 1988, a 21-hour unscripted mock trial was held on television, argued by lawyers before a judge,[279] with unscripted testimony from surviving witnesses to the events surrounding the assassination; the jury returned a verdict of guilty. In 1992, the American Bar Association conducted two mock Oswald trials. The first trial ended in a hung jury. In the second trial the jury acquitted Oswald.

See also

- John Wilkes Booth, assassin of President Abraham Lincoln

- Charles J. Guiteau, assassin of President James A. Garfield

- Leon Czolgosz, assassin of President William McKinley

- Sirhan Sirhan, assassin of Robert F. Kennedy

Notes

- ^ These were investigations by: the Federal Bureau of Investigation (1963), the Warren Commission (1964), the House Select Committee on Assassinations (1979), the Secret Service, and the Dallas Police Department.

- ^ The schools were: [citation needed]

- 1st grade: Benbrook Common School (Fort Worth, Texas), October 31, 1945

- 1st grade (again): Covington Elementary School (Covington, Louisiana), September 1946 – January 1947

- 1st grade (end): Clayton Public School (Ft Worth, TX), January–May 1947

- 2nd grade: Clayton Public School (Ft Worth, TX), September 1947

- 2nd grade (end): Clark Elementary School (Ft Worth, TX), March 1948

- 3rd grade: Arlington Heights Elementary School (Ft Worth, TX), September 1948

- 4th grade: Ridglea West Elementary School (since renamed Luella Merrett, Ft Worth), Sep. 1949

- 5th grade: Ridglea West Elementary School (Ft Worth), September 1950

- 6th grade: Ridglea West Elementary School (Ft Worth), September 1951

- 7th grade: Trinity Evangelical Lutheran School (Bronx, NYC, NY), August 1952

- 7th grade: Public School 117 (Bronx, NY), September 1952 (attended 17 of 64 days)

- 7th grade (end): Public School 44 (Bronx, NY), March 23, 1953

- Reformatory: Youth House (NYC, NY), April–May 1953.

- 8th grade: Public School 44 (Bronx, NY), September 14, 1953

- 8th grade (end): Beauregard Junior High School (New Orleans), January 13, 1954

- 9th grade: Beauregard Junior High School (New Orleans), September 1954 – June 1955

- 10th grade: Warren Easton High School (New Orleans), September–October 1955 (Warren appendix 13)

- (tried to enlist in U.S. Marines using affidavit claiming age 17)

- (worked as clerk/messenger in New Orleans, rather than school)

- 10th grade (again): Arlington Heights High School (Ft Worth, TX), September–October 1956. Final withdrawal from high school, 10th grade. (Warren appendix 13)

- ^ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 22, p. 705, CE 1385, Notes of interview of Lee Harvey Oswald Archived January 12, 2023, at the Wayback Machine conducted by Aline Mosby in Moscow in November 1959. Oswald: "When I was working in the middle of the night on guard duty, I would think how long it would be and how much money I would have to save. It would be like being out of prison. I saved about $1500." During Oswald's two years and ten months of service in the Marine Corps he received $3,452.20, after all taxes, allotments and other deductions as well as his GED. Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 26, p. 709, CE 3099, Certified military pay records for Lee Harvey Oswald for the period October 24, 1956, to September 11, 1959 Archived October 19, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Though later reports described her uncle, with whom she was living, as a colonel in the KGB, he was a lumber industry expert in the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD) with a bureaucratic rank of Polkovnik. Priscilla Johnson McMillan, Marina and Lee, Harper & Row, 1977, pp. 64–65. ISBN 978-0-06-012953-8.

- ^ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 11, p. 123, Affidavit of Alexander Kleinlerer Archived October 10, 2007, at the Wayback Machine: "Anna Meller, Mrs. Hall, George Bouhe, and the deMohrenschildts, and all that group had pity for Marina and her child. None of us cared for Oswald because of his political philosophy, his criticism of the United States, his apparent lack of interest in anyone but himself, and because of his treatment of Marina."

- ^ Warren Commission Hearings, Testimony of Dennis Hyman Ofstein: "I would say he didn't get along with people and that several people had words with him at times about the way he barged around the plant, and one of the fellows back in the photosetter department almost got in a fight with him one day, and I believe it was Mr. Graef that stepped in and broke it up before it got started..."

- ^ United States House Select Committee on Assassinations,

Testimony of Dr. Vincent P. Guinn Archived September 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine:

- Mr. WOLF. In your professional opinion, Dr. Guinn, is the fragment removed from General Walker's house a fragment from a WCC (Western Cartridge Company) Mannlicher–Carcano bullet?

- Dr. GUINN. I would say that it is extremely likely that it is, because there are very few, very few other ammunitions that would be in this range. I don't know of any that are specifically this close as these numbers indicate, but somewhere near them there are a few others, but essentially this is in the range that is rather characteristic of WCC Mannlicher–Carcano bullet lead.

- ^ Warren Commission Hearings, Testimony of Charles Givens Archived May 25, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Carolyn Arnold, the secretary to the Vice President of the TSBD, provided conflicting information on Oswald's whereabouts. In the first of two interviews with the FBI in the days following the assassination, Arnold stated that she my have "caught a fleeting glimpse" of someone she believed to be Oswald standing in the first-floor hallway of the building around 12:15 pm. In the second interview, she stated she did not see him at all. Although she signed her statement as correct, in 1978 she told author Anthony Summers that she had been misquoted by the FBI and that she had actually seen Oswald in the second floor lunchroom at 12:15 pm.(Posner 1993, pp. 225–226).

- ^ The first report of Tippit's shooting Archived February 4, 2010, at the Wayback Machine was transmitted over Police Channel 1 sometime between 1:16 and 1:19 p.m., as indicated by verbal time stamps made periodically by the dispatcher. Specifically, the first report began 1 minute 41 seconds after the 1: 16 time stamp. Before that, witness Domingo Benavides could be heard unsuccessfully trying to use Tippit's police radio microphone, beginning at 1:16. Dale K. Myers, With Malice: Lee Harvey Oswald and the Murder of Officer J.D. Tippit, 1998, p. 384. ISBN 0-9662709-7-5.

- ^ By the evening of November 22, five of them (Helen Markham, Barbara Jeanette Davis, Virginia Davis, Ted Callaway, Sam Guinyard) had identified Oswald in police lineups as the man they saw. A sixth (William Scoggins) did so the next day. Three others (Harold Russell, Pat Patterson, Warren Reynolds) subsequently identified Oswald from a photograph. Two witnesses (Domingo Benavides, William Arthur Smith) testified that Oswald resembled the man they had seen. One witness (L.J. Lewis) felt he was too distant from the gunman to make a positive identification. Warren Commission Hearings, CE 1968, Location of Eyewitnesses to the Movements of Lee Harvey Oswald in the Vicinity of the Tippit Killing Archived February 25, 2021, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Two misconceptions about the Warren Commission hearing need to be clarified ... hearings were closed to the public unless the witness appearing before the Commission requested an open hearing. No witness except one ... requested an open hearing ... Second, although the hearings (except one) were conducted in private, they were not secret. In a secret hearing, the witness is instructed not to disclose his testimony to any third party, and the hearing testimony is not published for public consumption. The witnesses who appeared before the Commission were free to repeat what they said to anyone they pleased, and all of their testimony was subsequently published in the first fifteen volumes put out by the Warren Commission." (Bugliosi, p. 332)

References

- ^ "John F Kennedy, Dallas Police Department Collection – The Portal to Texas History". May 26, 2023. Archived from the original on October 9, 2009. Retrieved September 6, 2013.

- ^ Tunheim, John R. (March 1, 1999). Final Report of the Kennedy Assassination Records Review Board. DIANE Publishing. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-7881-7722-4.

- ^ "Gallop: Most Americans Believe Oswald Conspired With Others to Kill JFK". Gallup.com. April 11, 2001. Archived from the original on January 8, 2009. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- ^ Pontchartrain, Blake (June 17, 2019). "Blake Pontchartrain: Where was the French Hospital in New Orleans, and what's its story?". The Advocate. Archived from the original on September 28, 2019. Retrieved September 29, 2019.

- ^ Child, Christopher C. (March 14, 2022). "Roosevelts without middle names". Vita Brevis. Archived from the original on May 25, 2022. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ "Notable Tomb Tuesday – Robert E. Lee Oswald, father of Lee Harvey Oswald". Lucky Bean Tours. January 2, 2017. Archived from the original on September 22, 2017. Retrieved September 22, 2017.

- ^ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 23, p. 799, CE 1963, Schedule showing known addresses of Lee Harvey Oswald from the time of his birth Archived January 11, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Robert Oswald, brother of Lee Harvey Oswald, dies at 83". Fort Worth Star Telegram. December 1, 2017. Archived from the original on December 12, 2017. Retrieved December 11, 2017.

- ^ Vaughn, Beverly (November 30, 2017). "Obituaries Robert Edward Lee Oswald". Times Record News. Archived from the original on December 4, 2017. Retrieved July 18, 2024.

- ^ a b "Appendix 13: Biography of Lee Harvey Oswald". Report of the President's Commission on the Assassination of President John F. Kennedy. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. 1964. pp. 697, 699. Archived from the original on April 8, 2020. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ^ a b Report of the President's Commission on the Assassination of President John F. Kennedy, Appendix 13 1964, pp. 674–675.

- ^ "Chapter 7: Lee Harvey Oswald: Background and Possible Motives". Report of the President's Commission on the Assassination of President John F. Kennedy. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. 1964. p. 378. Archived from the original on April 8, 2020. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ^ Report of the President's Commission on the Assassination of President John F. Kennedy, Appendix 13 1964, p. 676.

- ^ "Testimony of John Edward Pic". Warren Commission Hearings. Archived from the original on March 8, 2006. Retrieved January 31, 2006.

- ^ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 22, p. 687, CE 1382, Interview with Mrs. John Edward Pic Archived September 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Report of the President's Commission on the Assassination of President John F. Kennedy, Appendix 13 1964, p. 677.

- ^ a b c d e f "Chapter 7: Lee Harvey Oswald: Background and Possible Motives". Warren Commission Report. 1964. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved August 26, 2020.

- ^ Warren Commission Hearings, Testimony of John Carro Archived May 12, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Warren Commission Hearings, Testimony of Mrs. Marguerite Oswald Archived May 12, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Report of the President's Commission on the Assassination of President John F. Kennedy, Appendix 13 1964, p. 679.

- ^ a b c d Bagdikian, Ben H. (December 14, 1963). Blair, Clay Jr. (ed.). "The Assassin". The Saturday Evening Post (44). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The Curtis Publishing Company: 23.

- ^ Report of the President's Commission on the Assassination of President John F. Kennedy, Appendix 13 1964, p. 681.

- ^ Report of the President's Commission on the Assassination of President John F. Kennedy, Chapter 7 1964, p. 383.

- ^ Warren Commission Hearings, CE 2240, FBI transcript of letter from Lee Oswald to the Socialist Party of America, October 3, 1956 Archived September 30, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Oswald, David Ferrie and the Civil Air Patrol Archived April 11, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, United States House Select Committee on Assassinations, vol. 9, 4, p. 107.

- ^ Testimony of Edward Voebel Archived June 2, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 8, pp. 10, 12.

- ^ Oswald, David Ferrie and the Civil Air Patrol Archived January 11, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, House Select Committee on Assassinations – Appendix to Hearings, Volume 9, 4, pp. 107–115.

- ^ PBS Frontline "Who Was Lee Harvey Oswald" Archived September 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, broadcast on PBS stations, November 1993 (various dates).

- ^ a b Sanders, Bob Ray (November 25, 2013). "A Monday of Funerals, and Learning a Bit More about the Man Who Killed Kennedy". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. Archived from the original on December 2, 2013. Retrieved November 25, 2013.

- ^ Johnson McMillan, Priscilla (2013). "Interlude". Marina and Lee: The Tormented Love and Fatal Obsession Behind Lee Harvey Oswald's Assassination of John F. Kennedy. Hanover, New Hampshire: Steerforth Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-58642-217-2.

- ^ "Testimony of Mrs. Marguerite Oswald". Hearings Before the President's Commission on the Assassination of President John F. Kennedy, Volume I. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. 1964. p. 227. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- ^ Report of the President's Commission on the Assassination of President John F. Kennedy, Chapter 7 1964, p. 384.

- ^ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 19, Folsom Exhibit No. 1, p. 665, Administrative Remarks Archived June 2, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Report of the President's Commission on the Assassination of President John F. Kennedy, Appendix 13 1964, pp. 682–683.

- ^ "Appendix 13". Archives.gov. Archived from the original on May 19, 2016. Retrieved May 23, 2016.

- ^ "JFK". KerryThornley.com. Archived from the original on March 8, 2022. Retrieved April 11, 2022.

- ^ Lifton, David. "Garrison vs. Thornley: Part II" (PDF). Hood College, The Harold Weisberg Archive. Retrieved April 11, 2022.

- ^ Thornley, Kerry Wendell. Series: Records Relating to Key Persons, November 30, 1963 – September 24, 1964. National Archives Catalog, Records of the John F. Kennedy Assassination Collection: Key Persons Files. November 30, 1963. Archived from the original on April 13, 2022. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ^ Report of the President's Commission on the Assassination of President John F. Kennedy, Appendix 13 1964, p. 683.

- ^ Thornley, Kerry Wendell. Series: Records Relating to Key Persons, November 30, 1963 – September 24, 1964. National Archives Catalog. November 30, 1963. Archived from the original on April 13, 2022. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ^ "Chapter 4: The Assassin". Report of the President's Commission on the Assassination of President John F. Kennedy. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. 1964. p. 191. Archived from the original on April 8, 2020. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ^ Gerald Posner, Case Closed, Random House, New York, 1993 p. 28

- ^ "Affidavit of James Botelho" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

- ^ Oswald's Game. W W Norton & Co Inc. 2013. ISBN 978-1-4804-0287-4. Retrieved September 20, 2013.

- ^ Testimony of John E. Donovan Archived June 2, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 8, pp. 290–298.

- ^ Summers 1998, p. 94.

- ^ Summers 2013, pp. 140–141. The grades were −5 in understanding, +4 in reading and +3 in writing.

- ^ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 19, Folsom Exhibit No. 1, p. 85, Request for Dependency Discharge Archived September 30, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Warren Commission Hearings, Folsom Exhibit No. 1 (cont'd)". XIX Folsom: 734. Archived from the original on January 11, 2012. Retrieved June 5, 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Leskinen, M. & J. Keronen. Secret Helsinki. Jonglez Publishing, 2019. ISBN 978-2-36195-170-2

- ^ Lee Harvey Oswald in Russia, The Journey From USA to USSR Archived February 10, 2012, at the Wayback Machine at Russian Books

- ^ a b c Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 16, p. 94, CE 24, Lee Harvey Oswald's "Historic Diary" Archived January 11, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, entries of October 16, 1959, to October 21, 1959.

- ^ Kampeas, Ron (August 2, 2023). "New JFK documents reveal assassin's CIA monitor was Jewish spy Reuben Efron". The Times of Israel.

- ^ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 16, p. 95, CE 24, Lee Harvey Oswald's "Historic Diary" Archived May 25, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, entries of October 21, 1959, to October 28, 1959.

- ^ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 16, p. 96, CE 24, Lee Harvey Oswald's "Historic Diary" Archived April 4, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, entries of October 28, 1959, to October 31, 1959.

- ^ Lee Harvey Oswald in Russia, Moscow Part 1 Archived February 9, 2012, at the Wayback Machine at Russian Books

- ^ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 18, p. 108, CE 912, Declaration of Lee Harvey Oswald, dated November 3, 1959, requesting that his U.S. citizenship be revoked Archived January 11, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Texas Marine Gives Up U.S. For Russia"[permanent dead link], The Miami News, October 31, 1959, p. 1

- ^ Foreign Service Dispatch from the American Embassy in Moscow to the Department of State Archived May 28, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 18, p. 98, CE 908

- ^ Warren Commission Hearings, CE 780, Documents from Lee Harvey Oswald's Marine Corps file Archived April 4, 2023, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Former Marine Applies For Russ Citizenship". The Sacramento (CA) Bee. October 31, 1959. p. 27. Archived from the original on October 23, 2021. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ "Texan Asks Soviet Citizenship". The Times (Shreveport, LA). November 1, 1959. p. 22. Archived from the original on April 4, 2023. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ Report of the President's Commission on the Assassination of President John F. Kennedy, Appendix 13 1964, p. 697.

- ^ "Stanislau Shushkevich, biographical sketch (in Russian)". Nv-online.info. Archived from the original on March 16, 2012. Retrieved March 24, 2012.

- ^ Lee Harvey Oswald in Russia, Minsk Part 3 Archived February 3, 2012, at the Wayback Machine at Russian Books