A/UX

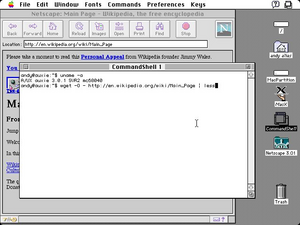

A/UX 3.0.1 with Finder, CommandShell, and Netscape | |

| Developer | Apple Computer |

|---|---|

| OS family | |

| Working state | Historic |

| Source model | Closed source |

| Initial release | February 1988[1] |

| Latest release | 3.1.1 / 1995 |

| Kernel type | Monolithic kernel |

| License | Proprietary |

A/UX is a Unix-based operating system from Apple Computer for Macintosh computers, integrated with System 7's graphical interface and application compatibility. It is Apple's first official Unix-based operating system, launched in 1988 and discontinued in 1995 with version 3.1.1.[2] A/UX requires select 68k-based Macintosh models with an FPU and a paged memory management unit (PMMU), including the Macintosh II, SE/30, Quadra, and Centris series.[3]

Described by InfoWorld as "an open systems solution with the Macintosh at its heart",[4] A/UX is based on UNIX System V Release 2.2, with features from System V Releases 3 and 4[citation needed] and BSD versions 4.2 and 4.3. It is POSIX- and System V Interface Definition (SVID)-compliant and includes TCP/IP networking since version 2. Having a Unix-compatible, POSIX-compliant operating system enabled Apple to bid for large contracts to supply computers to U.S. federal government institutes.[5][6]

Features

[edit]A/UX provides a graphical user interface including the familiar Finder windows, menus, and controls. The A/UX Finder is a customized version of the System 7 Finder, adapted to run as a Unix process and designed to interact with the underlying Unix file systems. A/UX includes the CommandShell terminal program, which offers a command-line interface to the underlying Unix system. An X Window System server application (called MacX) with a terminal program can also be used to interface with the system and run X applications alongside the Finder. Alternatively, the user can choose to run a fullscreen X11R4 session without the Finder.[4]

Apple's compatibility layer allows A/UX to run Macintosh System 7.0.1, Unix, and hybrid applications. A hybrid application uses functions from both the Macintosh toolbox and the Unix system. For example, it can run a Macintosh application which calls Unix system functions, or a Unix application which calls Macintosh Toolbox functions (such as QuickDraw), or a HyperCard stack graphical frontend for a command-line Unix application. A/UX's compatibility layer uses some existing Toolbox functions in the computer's ROM, while other function calls are translated into native Unix system calls; and it cooperatively multitasks all Macintosh apps in a single address space by using a token-passing system for their access to the Toolbox.[7]

A/UX includes a utility called Commando (similar to a tool of the same name included with Macintosh Programmer's Workshop) to assist users with entering Unix commands. Opening a Unix executable file from the Finder opens a dialog box that allows the user to choose command-line options for the program using standard controls such as radio buttons and check boxes, and display the resulting command line argument for the user before executing the command or program. This feature is intended to ease the learning curve for users new to Unix, and decrease the user's reliance on the Unix manual. A/UX has a utility that allows the user to reformat third-party SCSI drives in such a way that they can be used in other Macs of that era.[4]

A/UX requires 68k-based Macintoshes with a floating point unit (FPU) and a paged memory management unit (PMMU),[8] and select models. For example, the Quadra 840AV, the fastest 68k Macintosh, cannot run A/UX.[9]

History

[edit]A/UX 1.0 was announced at the February 1988 Uniforum conference, seven months behind schedule.[1] It is based on AT&T's Unix System V.2.2 with additional features from BSD Unix. Networking support includes TCP/IP, AppleTalk, and NFS implementations, developed by UniSoft.[10] The base system has no GUI, with only the command line. It can run one Macintosh application at a time, using the System 6 GUI interface, although it is compatible with only about 10% of the existing Macintosh software library.

It was initially aimed at existing Unix customers, universities and VARs.[11] The system was initially sold pre-installed on the Macintosh II for US$8,597 (equivalent to $22,100 in 2023), a larger monitor could be added, or a kit could upgrade an existing Mac II for a lower price.[1][11] Third-party software announced with the system's first release includes the Ingres database, StatView, developer tools, and various productivity software packages.[1][12]

Released in 1989, A/UX 1.1 supplies the basic GUI of System 6, with Finder, Chooser, Desk Accessories, and Control Panels. It provisions Unix with the X Window System (X11R3) GUI, the Draft 12 POSIX standard, and overall improved speed to competitive levels with Sun-3 desktop and deskside workstations, which used the same Motorola 68020 series CPU, FPU and MMU, none of which supported the exceptionally large RAM complement of 128MB at the time.[6][13][14] Having its first POSIX compliant platform allowed Apple to join "a growing list of industry heavyweights" to be allowed into the US federal government's burgeoning $6 billion bid market.[6]

In 1991, Apple's plans were influenced by the new AIM alliance with IBM, envisioning A/UX as becoming the basis for drastically scaling its concept of Macintosh system architecture and application compatibility across the computing industry, from personal to enterprise markets. Apple formed a new business division for enterprise systems led by director Jim Groff, to serve "large businesses, government, and higher education". Basing the division upon a maturing A/UX, Groff admitted that Apple was "not a major player" in the Unix market and had performed merely "quiet" marketing of the operating system, but fully intended to become a "major player" with "very broad-based marketing objectives" in 1992. Further, Apple believed the alliance with IBM would merge A/UX, AIX, and System 7—thus ultimately scaling the execution of Macintosh applications from Mac desktops to IBM's huge RS/6000 systems.[15]

In November 1991, Apple launched A/UX 3.0, planning to synchronize the two concurrent release schedules of A/UX and System 7. At that time, the company also preannounced A/UX 4.0, expected for release in 1993 or 1994. The announcement expounded upon the historic technology partnership between Apple and IBM, expecting to merge Apple's user-friendly graphical interface and desktop applications market with IBM's highly scalable Unix server market, and allowing the two companies to enter what Apple believed to be an emerging "general desktop open systems market". The upcoming A/UX 4.0 was proposed to target the PowerOpen Environment ABI, merge features of IBM's AIX variant of Unix into A/UX, and use the OSF/1 kernel from the Open Software Foundation. A/UX 3.0 was proposed to serve as an "important migration path" to this new system, making Unix and System 7 applications compliant with the PowerOpen specification.[4] The future A/UX 4.0 and AIX operating systems were intended to run on a variety of IBM's POWER and PowerPC hardware, and on Apple's PowerPC-based hardware.[15]

...Apple agreed to provide IBM with the technology needed to allow standard Macintosh applications—starting with the Finder—to run under the new AIX, much as they do under A/UX today. Apple will apply the PowerOpen label to the new version of A/UX that results from the deal; IBM will do likewise with the new AIX.

— MacWeek[16]

In April 1992, a C2-level secure version of A/UX was released.[17] Coincidentally, the AIM alliance had launched the Apple/IBM partnership corporation Taligent Inc. one month earlier, with the mission of bringing Apple's other next-generation operating system Pink to market as a grandly universal operating system and application framework.

Contrary to all announcements, Apple eventually abandoned all plans for the unreleased A/UX 4.0. In 1995, PowerOpen was discontinued and Apple withdrew from the Taligent Inc. partnership in December. In 1996, Apple discontinued its Copland project which had spent two years in the public view, intended to become Mac OS 8 and to host Taligent software. From 1996 to 1997, the company deployed a short-lived platform of Apple Network Server systems based upon PowerPC hardware and a customized IBM AIX operating system.[18] Apple's overall failed operating system strategy left it with the badly aged System 7 and no successor. Following its 1996 acquisition of NeXT, Apple introduced 1999's Mac OS X Server 1.0, a descendant of the Unix-based NeXTSTEP operating system.

The final release of A/UX is version 3.1.1 of 1995.[19] Apple had abandoned A/UX completely by 1996.[citation needed]

| Timeline of Mac operating systems |

|---|

|

Reception

[edit]A/UX 1.0 was criticized in the April 1988 InfoWorld review for having a largely command line interface as in other Unix variants, rather than graphical as in System 6; its networking support was praised, though.[20] BYTE in 1989 listed A/UX 1.1 among the "Excellence" winners of the BYTE Awards, stating that it "could make Unix the multitasking operating system of choice during the next decade" and challenge OS/2.[21] Compared to contemporary workstations from other Unix vendors, however, the Macintosh hardware lacks features such as demand paging. The first two versions A/UX consequently suffer from poor performance,[14] and poor sales.[4] Users also complained about the amount of hard drive space it uses on a standard Macintosh, though comparable to any Unix system.[6]

A/UX 3.0 was praised in the August 1992 issue of InfoWorld by the same author, describing it as "an open systems solution with the Macintosh at its heart" where "Apple finally gets Unix right". He praised the GUI, single-button point-and-click installer, one year of personal tech support, the graphical help dialogs, and the user's manuals, saying that A/UX "defies the stereotype that Unix is difficult to use" and is "the easiest version of Unix to learn". Its list price of $709 (equivalent to $1,500 in 2023) is much higher than that of "much weaker" competing PC operating systems such as System 7, OS/2, MS-DOS, and Windows 3.1, but low compared to the then prevailing proprietary Unix licenses of more than $2,000 (equivalent to $4,300 in 2023). The review found the system speed "acceptable but not great" even on the fastest Quadra 950, blaming not the software but the incomplete Unix optimization found in Apple's hardware. Though "a very good value", the system's price-performance ratio was judged as altogether uncompetitive against Sun's SPARCstation 2. The reviewers thought it unlikely for users "to want to buy Macs just to run A/UX" and would have awarded InfoWorld's top score if the OS was not proprietary to Macintosh hardware.[4]

Tony Bove of the Bove & Rhodes Report generally complained that "[f]or Unix super-users there is no compelling reason to buy Apple's Unix. For Apple A/UX has always been a way to sell Macs, not Unix; it's a check-off item for users."[15]

Legacy

[edit]Vintage A/UX users had one central repository for most A/UX applications: an Internet server at NASA called Jagubox. It was administered by Jim Jagielski, who was also the editor of the A/UX FAQ.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Executor, a third-party reverse-engineered reimplementation of System 7 as a Unix application

- Macintosh Application Environment, Apple's Mac OS application layer for third-party Unix systems

- Classic, a subsystem for Mac OS X

- macOS, Apple's current OS, descended from the Unix-based NeXTSTEP

- MachTen, Unix in the form of a Mac OS 7 application

- MacMach, an academic Mach-based Unix experiment providing System 7 as a Unix application

- MkLinux, Apple-sponsored Mach microkernel-based Linux on Macintosh hardware

- Star Trek project, System 7 ported as a DOS application for IBM PC clones

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Pitta, Julie (February 15, 1988). "A/UX ships following lengthy delay". Computerworld. Vol. XXII, no. 7. p. 133.

- ^ Flynn, Laurie (March 7, 1988). "Universities High on A/UX But Want More". InfoWorld. Vol. 10, no. 10. p. 31. Retrieved June 19, 2017.

- ^ "The Open Group official register of UNIX Certified Products". The Open Group. Retrieved October 1, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Crabb, Don (August 10, 1992). "Apple finally gets Unix right with A/UX 3.0". InfoWorld. Vol. 14, no. 32. pp. 68–69.

- ^ Betts, Mitch (August 8, 1988). "Uncle Sam Salutes the Mac". Computerworld. Vol. XXII, no. 32. p. 60.

- ^ a b c d Ryan, Alan J. (August 15, 1988). "Apple keen on Unix future". Computerworld. Vol. XXII, no. 33. p. 6.

- ^ Morley, John. "Macintosh Hybrid Applications for A/UX". MacTech. Retrieved October 3, 2017.

- ^ Singh, Amit (February 2004). "Many Systems for Many Apples". Kernel Thread. Archived from the original on February 21, 2009. Retrieved December 12, 2013.

- ^ "A/UX and Compatible Macintoshes". Apple, Inc. August 1994. Archived from the original on July 31, 2020.

- ^ Keefe, Patricia (March 2, 1987). "Apple brackets Unix, Ethernet". Computerworld. Vol. XXI, no. 9. p. 94.

- ^ a b Flynn, Laurie; Patton, Carole (February 22, 1988). "Apple breaks into Unix market with A/UX". InfoWorld. Vol. 10, no. 8. p. 31.

- ^ Flynn, Laurie (February 22, 1988). "Developers Eager to Display Programs Run Under A/UX". InfoWorld. Vol. 10, no. 8. p. 32.

- ^ Mace, Scott; Patton, Carole (August 8, 1988). "Apple to Support X Window in A/UX". InfoWorld. Vol. 10, no. 32. p. 5.

- ^ a b Marshall, Martin (January 16, 1989). "A/UX, Release 1.1 Supports X Window". InfoWorld. Vol. 11, no. 3. p. 31.

- ^ a b c Corcoran, Cate (November 4, 1991). "Apple reveals plans for updated A/UX, PowerOpen Unix development alliance". InfoWorld. Vol. 13, no. 44. pp. 1, 115–116.

- ^ "Forces Gather for PowerPC Roundtable". MacWeek. Vol. 7, no. 12. March 22, 1993. p. 38. Retrieved October 3, 2017.

- ^ Gillooly, Caryn (April 13, 1992). "Apple unveils secure A/UX for Macintosh networks". Network World. Vol. 9, no. 15. p. 13.

- ^ "Floodgap ANSwers: The AIX on ANS FAQ".

What versions of AIX does the ANS support? Only 4.1.4 (4.1.4.0 and 4.1.4.1) and 4.1.5, and then only Apple-branded versions

- ^ "A/UX FAQ".

- ^ Crabb, Don (April 4, 1988). "A/UX: This Operating System Is Far From Being "Unix for the Rest of Us"". InfoWorld. Vol. 11, no. 14. p. 43.

- ^ "The BYTE Awards". BYTE. Vol. 14, no. 1. January 1989. p. 327.