Clare Boothe Luce

Clare Boothe Luce | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Ambassador to Italy | |

| In office May 4, 1953 – December 27, 1956 | |

| President | Dwight D. Eisenhower |

| Preceded by | Ellsworth Bunker |

| Succeeded by | James David Zellerbach |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Connecticut's 4th district | |

| In office January 3, 1943 – January 3, 1947 | |

| Preceded by | Le Roy D. Downs |

| Succeeded by | John Lodge |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Ann Clare Boothe March 10, 1903 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | October 9, 1987 (aged 84) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 1 |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in the United States |

|---|

|

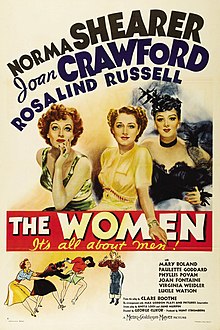

Clare Boothe Luce (née Ann Clare Boothe; March 10, 1903[1][2] – October 9, 1987) was an American writer, politician, U.S. ambassador, and public conservative figure. A versatile author, she is best known for her 1936 hit play The Women, which had an all-female cast. Her writings extended from drama and screen scenarios to fiction, journalism, and war reportage. She was married to Henry Luce, publisher of Time, Life, Fortune, and Sports Illustrated.

Politically, Luce was a leading conservative in later life and was well known for her anti-communism. In her youth, she briefly aligned herself with the liberalism of President Franklin Roosevelt as a protégé of Bernard Baruch but later became an outspoken critic of Roosevelt.[3] Although she was a strong supporter of the Anglo-American alliance in World War II, she remained outspokenly critical of British colonialism in India.[4]

Known as a charismatic and forceful public speaker, especially after her conversion to Catholicism in 1946, she campaigned for every Republican presidential candidate from Wendell Willkie to Ronald Reagan.

Early life

[edit]Luce was born Ann Clare Boothe in New York City on March 10, 1903, the second child of Anna Clara Schneider (also known as Ann Snyder Murphy, Ann Boothe, and Ann Clare Austin) and William Franklin Boothe (also known as "John J. Murphy" and "Jord Murfe").[5] Her parents were not married and would separate in 1912. Her father, a sophisticated man and a brilliant violinist,[6] instilled in his daughter a love of literature, if not of music, but had trouble holding a job and spent years as a traveling salesman. Parts of young Clare's childhood were spent in Memphis and Nashville, Tennessee, Chicago, Illinois, and Union City, New Jersey as well as New York City.[7] Clare Boothe had an elder brother, David Franklin Boothe.

She attended the cathedral schools in Garden City and Tarrytown, New York, graduating first in her class in 1919 at 16.[8] Her ambitious mother's initial plan for her was to become an actress. Clare understudied Mary Pickford on Broadway at age 10, and had her Broadway debut in Mrs. Henry B. Harris' production of "The Dummy" in 1914, a detective comedy. She then had a small part in Thomas Edison's 1915 movie, The Heart of a Waif.[9] After a tour of Europe with her mother and stepfather, Dr. Albert E. Austin, whom Ann Boothe married in 1919, she became interested in the women's suffrage movement, and she was hired by Alva Belmont to work for the National Woman's Party in Washington, D.C. and Seneca Falls, New York.[10]

She wed George Tuttle Brokaw, millionaire heir to a New York clothing fortune, on August 10, 1923, at the age of 20. They had one daughter, Ann Clare Brokaw (1924–1944) who was killed in a car accident. According to Boothe, Brokaw was a hopeless alcoholic, and the marriage ended in divorce on May 20, 1929.[11]

On November 23, 1935, she married Henry Luce, the publisher of Time, Life, and Fortune. She thereafter called herself Clare Boothe Luce, a frequently misspelled name that was often confused with that of her exact contemporary Claire Luce, a stage and film actress. As a professional writer, Luce continued to use her maiden name.

In 1939 she commissioned Frida Kahlo to paint a portrait of the late Dorothy Hale. Kahlo produced The Suicide Of Dorothy Hale. Luce was appalled and almost destroyed it; however, Isamu Noguchi dissuaded her. Luce later anonymously donated the painting to the Phoenix Art Museum.[12]

On January 11, 1944, her only child, Ann Clare Brokaw, a 19-year-old senior at Stanford University, was killed in an automobile accident.[13] As a result of the tragedy, Luce explored psychotherapy and religion. After grief counseling with Bishop Fulton Sheen, she was received into the Catholic Church in 1946.[14] She became an ardent essayist and lecturer in celebration of her faith, and she was ultimately honored by being named a Dame of Malta. As a memorial to her daughter, beginning in 1949 she funded the construction of a Catholic church in Palo Alto for use by the Stanford campus ministry. The new Saint Ann Chapel was dedicated in 1951. It was sold by the diocese in 1998 and in 2003 became a church of the Anglican Province of Christ the King.[15]

Marriage to Henry Luce

[edit]The marriage between Clare and Henry was difficult. Henry was by any standard extremely successful, but his physical awkwardness, lack of humor, and newsman's discomfort with any conversation that was not strictly factual put him in awe of his beautiful wife's social poise, wit, and fertile imagination.[16] Clare's years as managing editor of Vanity Fair left her with an avid interest in journalism (she suggested the idea of Life magazine to her husband before it was developed internally).[17] Henry himself was generous in encouraging her to write for Life, but the question of how much coverage she should be accorded in Time, as she grew more famous, was always a careful balancing act for Henry since he did not want to be accused of nepotism.

It has been reported that their marriage was sexually "open".[18] Clare Luce's lovers included Ambassador Joseph P. Kennedy, Randolph Churchill, General Lucian Truscott, General Charles Willoughby,[19] and Roald Dahl.

Joseph P. Kennedy was the father of several United States politicians. Clare Luce at times provided advice to the campaigns of John F. Kennedy, who became the 35th U.S. president.

Dahl, who became a very successful author after the war, was at the time a dashing young RAF fighter pilot, temporarily assigned to Washington. He was part of a plan developed by spymaster Sir William Stephenson (code name "Intrepid"), intended to weaken American isolationist thinking by influencing, among others, American journalists and politicians. Dahl was

instructed to romance Clare, who was thirteen years his senior, to see if, with the right kind of encouragement, she could warm to the British position.

The very tall (6'6") and athletic Dahl later claimed he found his affair with Clare to be so physically demanding that he had begged the British ambassador to relieve him of the task, but the ambassador told him he must continue.[20]

In the early 1960s, both Luces were friends of philosopher, author, and LSD advocate Gerald Heard.[21] They tried LSD one time under his careful supervision. Although taking LSD never turned into a habit for either of the Luces, a friend (and biographer of Clare), Wilfred Sheed, wrote that Clare made use of it at least several times.[22]

The Luces stayed together until Henry's death from a heart attack in 1967. As one of the great "power couples" in American history, they were bonded by their mutual interests and complementary, if contrasting, characters. They treated each other with unfailing respect in public, never more so than when he willingly acted as his wife's consort during her years as ambassador to Italy. She was never able to convert him to Catholicism (he was the son of a Presbyterian missionary) but he did not question the sincerity of her faith, often attended Mass with her, and defended her when she was criticized by his fellow Protestants.

In the early years of her widowhood, she retired to the luxurious beach house that she and her husband had planned in Honolulu, but boredom with life in what she called "this fur-lined rut"[23] brought her back to Washington, D.C. for increasingly long periods. She made her final home there in 1983.

Writing career

[edit]

A writer with considerable powers of invention and wit, Luce published Stuffed Shirts, a promising volume of short stories, in 1931. Scribner's Magazine compared the work to Evelyn Waugh's Vile Bodies for its bitter humor. The New York Times found it socially superficial, but praised its "lovely festoons of epigrams" and beguiling stylishness: "What malice there may be in these pages has a felinity that is the purest Angoran."[24] The book's device of characters interlinked from story to story was borrowed from Sherwood Anderson's Winesburg, Ohio (1919), but it impressed Andre Maurois, who asked Luce's permission to imitate it.[25] Luce also published many magazine articles. Her real talent, however, was as a playwright.

After the failure of her initial stage effort, the marital melodrama Abide With Me (1935), she rapidly followed up with a satirical comedy, The Women. Deploying a cast of no fewer than 40 actresses who discussed men in often scorching language, it became a Broadway smash in 1936 and, three years later, a successful Hollywood movie known for its exclusively female cast. Toward the end of her life, Luce claimed that for half a century, she had steadily received royalties from productions of The Women all around the world. Later in the 1930s, she wrote two more successful, but less durable plays, also both made into movies: Kiss the Boys Goodbye and Margin for Error. The latter work "presented an all-out attack on the Nazis' racist philosophy".[26] Its opening night in Princeton, New Jersey, on October 14, 1939, was attended by Albert Einstein and Thomas Mann. Otto Preminger directed and starred in both the Broadway production and screen adaptation.[27]

Much of Luce's famously acid wit ("No good deed goes unpunished",[28] "Widowhood is a fringe benefit of marriage", "A hospital is no place to be sick") can be traced back to the days when, as a wealthy young divorcee in the early 1930s, she became a caption writer at Vogue and then, associate editor and managing editor of Vanity Fair. She not only edited the works of such great humorists as P. G. Wodehouse and Corey Ford but also contributed many comic pieces of her own, signed and unsigned. Her humor, which she retained into old age, was one of the pillars of Clare's character.

Another branch of Luce's literary career was that of war journalism. Europe in the Spring was the result of a four-month tour of Britain, Belgium, the Netherlands, Italy, and France in 1939–1940 as a correspondent for Life magazine. She described the widening battleground of World War II as "a world where men have decided to die together because they are unable to find a way to live together."[29]

In 1941, Luce and her husband toured China and reported on the status of the country and its war with Japan. Her profile of General Douglas MacArthur was on the cover of Life on December 8, 1941, the day after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. After the United States entered the war, Luce toured military installations in Africa, India, China, and Burma, compiling a further series of reports for Life. She published interviews with General Harold Alexander, commander of British troops in the Middle East, Chiang Kai-shek, Jawaharlal Nehru, and General Stilwell, commander of American troops in the China-Burma-India theater.[29]

Her lifelong instinct for being in the right place at the right time and easy access to key commanders made her an influential figure on both sides of the Atlantic. She endured bombing raids and other dangers in Europe and the Far East. She did not hesitate to criticize the unwarlike lifestyle of General Sir Claude Auchinleck's Middle East Command in language that recalled the barbs of her best playwriting. One draft article for Life, noting that the general lived far from the Egyptian front in a houseboat, and mocking RAF pilots as "flying fairies", was discovered by British Customs when she passed through Trinidad in April 1942. It caused such Allied consternation that she briefly faced house arrest.[30] Coincidentally or not, Auchinleck was fired a few months later by Winston Churchill. Her varied experiences in all the major war theaters qualified her for a seat the following year on the House Military Affairs Committee after she was elected to the United States House of Representatives in 1942.[citation needed]

Luce never wrote an autobiography but willed her enormous archive of personal papers to the Library of Congress.[31]

Political career

[edit]House of Representatives

[edit]In 1942, Luce won a Republican seat in the United States House of Representatives comprising the whole of Fairfield County, Connecticut, the 4th Congressional District. She based her platform on three goals: "One, to win the war. Two, to prosecute that war as loyally and effectively as we can as Republicans. Three, to bring about a better world and a durable peace, with special attention to post-war security and employment here at home."[32] She took up the seat formerly held by her late stepfather, Dr. Albert Austin. An outspoken critic of Roosevelt's foreign policy,[32] Luce was supported by isolationists and conservatives in Congress, and she was appointed early to the prestigious House Military Affairs Committee. Although she was by no means the only female representative on the floor, her beauty, wealth, and penchant for slashing witticisms caused her to be treated patronizingly by colleagues of both sexes.[33] She made a sensational debut in her maiden speech, coining the phrase "globaloney" to disparage Vice President Henry Wallace's recommendation for airlines of the world to be given free access to US airports.[34] She called for repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act, comparing its "doctrine of race theology" to Adolf Hitler's,[35] advocated aid for war victims abroad, and sided with the administration on issues such as infant-care and maternity appropriations for the wives of enlisted men. Nevertheless, Roosevelt took a dislike to her and campaigned in 1944 to attempt to prevent her re-election, publicly calling her "a sharp-tongued glamor girl of forty."[36] She retaliated by accusing Roosevelt of being "the only American president who ever lied us into a war because he did not have the political courage to lead us into it."[37]

During her second term, Luce was instrumental in the creation of the Atomic Energy Commission[38] and, during the course of two tours of Allied battlefronts in Europe, she campaigned for more support of what she considered to be America's forgotten army in Italy. She was present at the liberation of several Nazi concentration camps in April 1945, and after V-E Day, she began warning against the rise of international Communism as another form of totalitarianism, likely to lead to World War III.[32]

In 1946, she was the co-author of the Luce–Celler Act of 1946, which permitted Indians and Filipinos to immigrate to the US, introducing a quota of 100 immigrants from each country, and allowed them ultimately to become naturalized citizens.[39]

Luce did not run for re-election in 1946.

Ambassador to Italy

[edit]

Luce returned to politics during the 1952 presidential election: she campaigned on behalf of Republican candidate Dwight Eisenhower, giving more than 100 speeches on his behalf. Her anti-Communist speeches on the stump, radio, and television were effective in persuading a large number of traditionally Democratic-voting Catholics to switch parties and vote Eisenhower. For her contributions Luce was rewarded with an appointment as ambassador to Italy, a post that oversaw 1150 employees, 8 consulates, and 9 information centers. She was confirmed by the Senate in March 1953, the first American woman ever to hold such an important diplomatic post.

Italians reacted skeptically at first to the arrival of a female ambassador in Rome, but Luce soon convinced those of moderate and conservative temper that she favored their civilization and religion. "Her admirers in Italy – and she had millions – fondly referred to her as la Signora, 'the lady'."[40] The country's large Communist minority, however, regarded her as a foreign meddler in Italian affairs. Luce was pictured with Monsignor William A. Hemmick, the first American canon of St. Peter's Basilica, in the biography of Hemmick, Patriot Priest.[41]

She was no stranger to Pope Pius XII, who welcomed her as a friend and faithful acolyte.[42] Over the course of several audiences since 1940, Luce had impressed Pius XII as one of the most effective secular preachers of Catholicism in America.[43]

Her principal achievement as ambassador was to play a vital role in negotiating a peaceful solution to the Trieste Crisis of 1953–1954, a border dispute between Italy and Yugoslavia that she saw as potentially escalating into a war between East and West. Her sympathies throughout were with the Christian Democratic government of Giuseppe Pella, and she was influential on the Mediterranean policy of Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, another anticommunist. Although Luce regarded the abatement of the acute phase of the crisis in December 1953 as a triumph for herself, the main work of settlement, finalized in October 1954, was undertaken by professional representatives of the five concerned powers (Britain, France, the United States, Italy, and Yugoslavia) meeting in London.[44]

As ambassador, Luce consistently overestimated the possibility that the Italian left would mount a governmental coup and turn the country communist unless the democratic center was buttressed with generous American aid. A United States Defense Department historical study declassified in 2016 revealed that during her time as ambassador, Luce oversaw a covert financial support program for centrist Italian governments aimed at weakening the Italian Communist Party's hold on labor unions.[45]

Nurturing an image of her own country as a haven of social peace and prosperity, she threatened to boycott the 1955 Venice Film Festival if the American juvenile delinquent film Blackboard Jungle was shown.[46] Around the same time, she fell seriously ill with arsenic poisoning. Sensational rumors circulated that the ambassador was the target of extermination by agents of the Soviet Union. Medical analysis eventually determined that the poisoning was caused by arsenate of lead in paint dust falling from the stucco that decorated her bedroom ceiling. The episode debilitated Luce physically and mentally, and she resigned her post in December 1956.[47] Upon her departure, Rome's Il Tempo concluded "She has given a notable example of how well a woman can discharge a political post of grave responsibility."[48]

In 1957, she was awarded the Laetare Medal by the University of Notre Dame, considered the most prestigious award for American Catholics.[49]

A great appreciator of Italian haute couture, she was a frequent visitor and client of the ateliers Gattinoni, Ferdinandi, Schuberth, and Sorelle Fontana in Rome.

Ambassador to Brazil nomination

[edit]In April 1959, President Eisenhower nominated a recovered Luce to be the US Ambassador to Brazil. She began to learn enough of the Portuguese language in preparation for the job, but she was by now so conservative that her appointment met with strong opposition from a small number of Democratic senators. Leading the charge was Oregon Senator Wayne Morse. Still, Luce was confirmed by a 79 to 11 vote. Her husband urged her to decline the appointment, noting that it would be difficult for her to work with Morse, who chaired the Senate Subcommittee on Latin American Affairs. Luce eventually sent Eisenhower a letter explaining that she felt that the controversy surrounding her appointment would hinder her abilities to be respected by both her Brazilian and US coworkers. Thus, as she had never left American soil, she never officially took office as ambassador.[50]

Political life after office

[edit]After Fidel Castro led a revolution in Cuba in 1959, Luce and her husband began to sponsor anticommunist groups. This support included funding Cuban exiles in commando speedboat raids against Cuba in the early 1960s.[51][52] Luce's continuing anticommunism as well as her advocacy of conservatism led her to support Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona as the Republican candidate for president in 1964. She also considered but rejected a candidacy for the United States Senate from New York on the Conservative party ticket. That same year, which also saw the political emergence of future friend Ronald Reagan, marked the voluntary end of Henry Luce's tenure as editor-in-chief of Time. The Luces retired together, establishing a winter home in Arizona and planning a final move to Hawaii. Her husband, Henry, died in 1967 before that dream could be realized, but she went ahead with construction of a luxurious beach house in Honolulu, and, for some years, she led an active life in Hawaii high society.

In 1973, President Richard Nixon named her to the President's Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board (PFIAB). She remained on the board until President Jimmy Carter succeeded President Gerald Ford in 1977. By then, she had put down roots in Washington, D.C., that would become permanent in her last years. In 1979, she was the first woman to be awarded the Sylvanus Thayer Award by the United States Military Academy at West Point.

President Reagan reappointed Luce to PFIAB. She served on the board until 1983.

In 1986, Luce was the recipient of the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement.[53]

Presidential Medal of Freedom

[edit]President Reagan awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom[54] in 1983. She was the first female member of Congress to receive this award.[55]

Upon presenting her with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, Reagan said this of Luce:

A novelist, playwright, politician, diplomat, and advisor to Presidents, Clare Boothe Luce has served and enriched her country in many fields. Her brilliance of mind, gracious warmth and great fortitude have propelled her to exceptional heights of accomplishment. As a Congresswoman, Ambassador, and Member of the President's Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board, Clare Boothe Luce has been a persistent and effective advocate of freedom, both at home and abroad. She has earned the respect of people from all over the world, and the love of her fellow Americans.[56]

Death

[edit]Luce died of brain cancer on October 9, 1987, at age 84, at her Watergate apartment in Washington, D.C.[57] She is buried at Mepkin Abbey, South Carolina, a plantation that she and Henry Luce had once owned and given to a community of Trappist monks. She lies in a grave adjoining her mother, daughter, and husband.[58]

Legacy

[edit]Feminism

[edit]Revered in her later years as a heroine of the feminist movement, Luce had mixed feelings about the role of women in society. As a congresswoman in 1943, she was invited to co-sponsor a submission of the Equal Rights Amendment, offered by Representative Louis Ludlow of Indiana, but claimed that the invitation got lost in her mail.[59] Luce never ceased to advise women to marry and provide supportive homes for their husbands. (During her ambassadorial years, at a dinner in Luxembourg attended by many European dignitaries, Luce was heard declaiming that all women wanted from men was "babies and security".)[60] Yet, her own professional career as a successful editor, writer, playwright, reporter, legislator, and diplomat remarkably showed how a woman of humble origins and no college education could raise herself to an escalating series of public heights. Luce bequeathed a large part of her personal fortune of some $50 million to an academic program, the Clare Boothe Luce Program, designed to encourage the entry of women into technological fields traditionally dominated by men. Because of her determination and unwillingness to let her gender stand in the way of her personal and professional achievements, Luce is considered to be an influential role model by many women. Starting from humble beginnings, Luce never allowed her initial poverty or her male counterparts' lack of respect to keep her from achieving as much as if not more than many of the men surrounding her.[citation needed] In 2017, she was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame.[61]

Clare Boothe Luce Program

[edit]Since 1989, the Clare Boothe Luce Program (CBLP) has become a significant source of private funding support for women in science, mathematics, and engineering. All awards must be used exclusively in the United States (not applicable for travel or study abroad). Student recipients must be U.S. citizens and faculty recipients must be citizens or permanent residents. Thus far, the program has supported more than 1,500 women.

The terms of the bequest require the following criteria:

- at least fifty percent of the awards go to Roman Catholic colleges, universities, and one high school (Villanova Preparatory School)

- grants are made only to four-year degree-granting institutions, not directly to individuals

The program is divided into three distinct categories:

- undergraduate scholarships and research awards

- graduate and post-doctoral fellowships

- tenure-track appointment support at the assistant or associate professorship level[38]

Conservatism

[edit]The Clare Boothe Luce Policy Institute (CBLPI) was founded in 1993 by Michelle Easton.[62] The non-profit think tank seeks to advance American women through conservative ideas and espouses much the same philosophy as that of Clare Boothe Luce, in terms of both foreign and domestic policy.[63] The CBLPI sponsors a program that brings conservative speakers such as conservative commentator Ann Coulter to college campuses.[64]

The Clare Boothe Luce Award, established in 1991, is The Heritage Foundation's highest award for distinguished contributions to the conservative movement. Prominent recipients include Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher, and William F. Buckley Jr.[65][66][67]

Publications

[edit]- Plays

- 1935 Abide with Me

- 1936 The Women

- 1938 Kiss the Boys Goodbye

- 1939 Margin for Error

- 1951 Child of the Morning

- 1970 Slam the Door Softly

- Screen Stories

- 1949 Come to the Stable

- Books

- 1931 Stuffed Shirts

- 1940 Europe in the Spring

- 1952 Saints for Now (editor)

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Morris, Sylvia Jukes (January 31, 1988). "In Search of Clare Boothe Luce". The New York Times Magazine. pp. 4 of 5. Retrieved June 19, 2014.

I tracked down her New York birth certificate, and found that she was born not on April 10, 1903, but on March 10 – and not on Riverside Drive, but in the less genteel environs of West 125th Street.

- ^ Clare Boothe Luce's authorized biographer has corrected the misperception, encouraged by Luce herself, that she was born a month later: "I tracked down her New York birth certificate and found that she was born not on April 10, 1903 but on March 10—and not on Riverside Drive but in the less genteel environs of West 125th Street. I told her about the dates and she stared at me. 'Mother always said I was born at Easter. Anyway ... people born under the Aries sign are much more lighthearted and gay than those born under Pisces.'" Sylvia Jukes Morris, "In Search of Clare Boothe Luce", The New York Times Magazine, January 31, 1988

- ^ Morris 1997, pp. 191–98.

- ^ Clare Boothe Luce, Address to the India League of America, August 9, 1943, Clare Boothe Luce Papers, Library of Congress (hereafter CBLP-LC).

- ^ Morris 1997, pp. 15–32.

- ^ Morris 1997, pp. 17–18, 152–53.

- ^ Morris 1997, pp. 29–42.

- ^ Lyons, Joseph (1989). Clare Boothe Luce, Author and Diplomat. Chelsea House. p. 26.

- ^ Morris 1997, pp. 49–52.

- ^ Morris 1997, pp. 110–14, 120–21.

- ^ Morris 1997, pp. 130–31, 146–48.

- ^ Herrera, Hayden (1983). Frida, a biography of Frida Kahlo. New York: Harper and Row. p. 290 (footnote). ISBN 978-0-06-011843-3.

- ^ "Ann Brokaw Dies in Auto Collision", The New York Times, January 12, 1944. Accessed August 2, 2009.

- ^ The New York Times, February 17, 1946.

- ^ "A Spiritual Home Finds Salvation" Archived April 2, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Stanford Magazine, July/August 2006. Accessed August 2, 2009. Ann Brokaw graduated cum laude from Foxcroft School in Middleburg, Virginia at the age of 17 and went to Stanford University as a way to see the western United States. Hatch, Alden (1956). Ambassador Extraordinary. New York: Holt and Company. While at Stanford she was a member of the Kappa Kappa Gamma sorority.

- ^ Morris 1997, pp. 284–85, 306–08, 357–64.

- ^ Morris 1997, pp. 283–84, 291.

- ^ Nasah, David 2012 Patriarch: The Remarkable Life and Turbulent Times of Joseph P. Kennedy Penguin

- ^ Morris, Sylvia Jukes 2014 Price of Fame: The Honorable Clare Boothe Luce Random House

- ^ Jennet Conant. The Irregulars: Roald Dahl and the British Spy Ring in Wartime Washington. Simon & Schuster. New York. 2008. pp. 120–121

- ^ "Gerald Heard – The official Gerald Heard Website". Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ^ Sheed, Wilfred 1982 Clare Boothe Luce. Berkley: New York, p. 125

- ^ Sylvia Jukes Morris, "In Search of Clare Boothe Luce", The New York Times Magazine, January 31, 1988.

- ^ Morris 1997, pp. 188–89.

- ^ Morris 1997, p. 182.

- ^ Lyons (1989), Clare Boothe Luce, Author and Diplomat, p. 61.

- ^ Morris 1997, pp. 351–55, 368.

- ^ The famous quip was first quoted in print by Luce's social secretary Letitia Baldrige in Roman Candle (Houghton Mifflin, Boston, 1956), 129: "When I would entreat her to engage in resolving a specific case, she replied, 'No good deed goes unpunished, Tish, remember that.'" Oscar Wilde, Billy Wilder, and Andrew W. Mellon have also been cited as sources, but without written evidence.

- ^ a b "Women Come to Front: Journalist, Photographers and Broadcaster During WWII". Library of Congress. July 27, 2010. Retrieved May 30, 2012.

- ^ Morris 1997, p. 458.

- ^ Library of Congress, https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms003044

- ^ a b c "Clare Boothe Luce, Representative, 1943–1947, Republican from Connecticut". Office of the Clerk U.S. Capitol, Room H154. Archived from the original on June 18, 2012. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ William Miller, Fishbait (New York, 1977), 67; Clare Boothe Luce to Pearl S. Buck, July 20, 1959, Clare Boothe Luce Papers, Library of Congress

- ^ "America in the Post-War Air World", speech by Clare Boothe Luce, Congresswoman from Connecticut, delivered in the House of Representatives, Washington D.C., February 9, 1943. Vital Speeches of the Day, 1943, 331–36.

- ^ Palm Beach Post, July 7, 1943.

- ^ New York Sun, November 8, 1944.

- ^ The New York Times, October 14, 1944.

- ^ a b "Clare Boothe Luce". The Henry Luce Foundation, Inc. Archived from the original on May 18, 2012. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ Harold A. Gould, Sikhs, Swamis, Students and Spies: The India Lobby in the United States, 1900–1946, Sage Publications, 2006, pp. 393–431.

- ^ Lyons, Joseph. CBL, Author and Diplomat. p. 91.

- ^ "William Anthony Hemmick - World War I Centennial".

- ^ A popular joke of the time alleged that Luce urged Pius XII to be tougher on communism in defense of the Church, prompting the Pontiff to reply, "You know, Mrs. Ambassador, I am a Catholic too." Paolucci, Antonio (September 13–14, 2010). "La salvaguardia della Sistina. Stiano tranquilli i consiglieri troppo zelanti" [Sistine chapel safeguard. Too zealous counselors be quiet.]. L'Osservatore Romano (in Italian). www.chiesa.espressonline.it. Retrieved September 14, 2011.

Signora sono cattolico anch'io

- ^ Fr. Wilfred Thibodeau to Clare Boothe Luce, August 12, 1949, Luce Papers, Library of Congress. In 1957, Luce was awarded the Laertare Medal as an outstanding Catholic layperson. She also received honorary degrees from both Fordham and Temple universities.

- ^ Osvaldo Croci, "The Trieste Crisis, 1953", Ph.D. thesis, McGill University, 1991.

- ^ Dr. Ronald D. Landa, ed. (February 7, 2017). "CIA Covert Aid to Italy Averaged $5 Million Annually from Late 1940s to Early 1960s, Study Finds". National Security Archive. Retrieved August 17, 2018.

- ^ "Envoy Stops Showing of Blackboard Jungle". The Age. August 29, 1955.

- ^ "Foreign Relations: Arsenic for the Ambassador", Time, July 23, 1956.

- ^ Alef, Daniel. Clare Boothe Luce: Renaissance Woman.

- ^ "Recipients". The Laetare Medal. University of Notre Dame. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- ^ "The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project Women Ambassadors Series AMBASSADOR CLARE BOOTHE LUCE" (PDF). Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training. June 19, 1986. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 27, 2024. Retrieved July 25, 2024.

- ^ Summers, Anthony. Not in Your Lifetime, (New York: Marlowe & Company, 1998), p. 322. ISBN 1-56924-739-0

- ^ Fonzi, Gaeton. The Last Investigation, (New York: Thunder's Mouth Press, 1993), pp. 53–54. ISBN 1-56025-052-6

- ^ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ "Writer, Diplomat Clare Boothe Luce". Clare Boothe Luce Policy Institute. Archived from the original on April 21, 2012. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ Homan, Paul (October 5, 2011). "Women in Government: Clare Boothe Luce". Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ "Remarks at the Presentation Ceremony for the Presidential Medal of Freedom". East Room at the White House: University of Texas. February 23, 1983. Archived from the original on October 11, 2009. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ "Clare Boothe Luce, one of America's most versatile and..." United Press International. October 9, 1987. Retrieved October 7, 2021.

- ^ Brenner, Marie (March 1988). "Fast and Luce". Vanity Fair. No. March. ISSN 0733-8899.

- ^ Bridgeport [CT] Herald, February 28, 1943.

- ^ C. L. Sulzberger, A Long Row of Candles (Macmillan, New York, 1969), 916.

- ^ "Ten women added to National Women's Hall of Fame in Seneca". Localsyr.com. September 17, 2017. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- ^ "About – Clare Boothe Luce Policy Institute". cblpi.org. Archived from the original on August 31, 2009. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

- ^ "Issues – Clare Boothe Luce Policy Institute". cblpi.org. Archived from the original on August 26, 2013.

- ^ Schreiber, Ronnee (2008). Righting Feminism: Conservative Women and American Politics. Oxford University Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-19-533181-3.

- ^ Rankin, Margaret (December 12, 1997). "Heritage of conservatism is ongoing after 25 years". The Washington Times.

- ^ "Thatcher praises Blair's support for US". BBC News. December 10, 2002. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

- ^ "William F. Buckley Jr". National Review Online. May 18, 2006. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

References

[edit]- Morris, Sylvia Jukes (1997). Rage for Fame: The Ascent of Clare Boothe Luce. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0394575551.

- Morris, Sylvia Jukes (2014). Price of Fame: The Honorable Clare Boothe Luce. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0679457114.

- Shadegg, Stephen (1970). Clare Boothe Luce: A Biography. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0671206727.

- Sheed, Wilfred (1982). Clare Boothe Luce. New York: E. P. Dutton Publishers. ISBN 978-0525030553.

- Hamilton, Pamela (2021). Lady Be Good[1]

External links

[edit]- United States Congress. "Clare Boothe Luce (id: l000497)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Clare Boothe Luce at IMDb

- Clare Boothe Luce at the Internet Broadway Database

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Library of Congress website

- Henry Luce profile

- Clare Boothe Luce Policy Institute website

- A film clip "Longines Chronoscope with Clare Boothe Luce" is available for viewing at the Internet Archive

- A film clip "Longines Chronoscope with Clare Boothe Luce (October 24, 1952)" is available for viewing at the Internet Archive

- ^ Hamilton, Pamela (2021). Lady Be Good (1st ed.). New York: Koehler Books. pp. 16–265. ISBN 978-1646632725.

- 1903 births

- 1987 deaths

- 20th-century American diplomats

- 20th-century American dramatists and playwrights

- 20th-century American legislators

- 20th-century American non-fiction writers

- 20th-century American women journalists

- 20th-century American women politicians

- 20th-century American women writers

- 20th-century Roman Catholics

- Ambassadors of the United States to Italy

- American anti-communists

- American anti-fascists

- American Roman Catholic writers

- American women ambassadors

- American women dramatists and playwrights

- American women in politics

- American women non-fiction writers

- Aphorists

- Burials in South Carolina

- Catholics from Connecticut

- Converts to Roman Catholicism

- Dames of Malta

- Deaths from brain cancer in Washington, D.C.

- Female critics of feminism

- Female members of the United States House of Representatives

- Laetare Medal recipients

- People from Ridgefield, Connecticut

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- Republican Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Connecticut

- Ward–Belmont College alumni

- Women in Connecticut politics

- Writers from Connecticut

- Writers from New York City