Intellect

In the study of the human mind, intellect is the ability of the human mind to reach correct conclusions about what is true and what is false in reality; and includes capacities such as reasoning, conceiving, judging, and relating.[1] Translated from the Ancient Greek philosophical concept nous, intellect derived from the Latin intelligere ("to understand"), from which the term intelligence in the French and English languages is also derived. The discussion of intellect can be divided into two areas that concern the relation between intelligence and intellect.[2]

- In classical philosophy and in medieval philosophy the intellect (nous) is the subject of the question: How do people know things? In Late Antiquity and in the Middle Ages, the intellect was the conceptual means of reconciling religious monotheism with philosophical or scientific study of Nature. This reconciliation made the intellect the conduit between the individual human soul, and the divine intellect of the cosmos. Aristotle first developed this with his distinction between the passive intellect and active intellect.[3]

- In psychology and in neuroscience, the controversial Theory of Multiple Intelligences applies the terms intelligence (emotion) and intellect (mind) to describe how people understand the world and reality.[4]

Intellect and intelligence

[edit]As a branch of intelligence, intellect concerns the logical and the rational functions of the human mind, and usually is limited to facts and knowledge.[5] Additional to the functions of linear logic and the patterns of formal logic the intellect also processes the non-linear functions of fuzzy logic and dialectical logic.[6]

Intellect and intelligence are contrasted by etymology; derived from the Latin present active participle intelligere, the term intelligence denotes "to gather in between", whereas the term intellect, derived from the past participle of intelligere, denotes "what has been gathered". Therefore, intelligence relates to the creation of new categories of understanding, based upon similarities and differences, while intellect relates to understanding existing categories.[7]

Development of intellect

[edit]

A person's intellectual understanding of reality derives from a conceptual model of reality based upon the perception and the cognition of the material world of reality. The conceptual model of mind is composed of the mental and emotional processes by which a person seeks, finds, and applies logical solutions to the problems of life. The full potential of the intellect is achieved when a person acquires a factually accurate understanding of the real world, which is mirrored in the mind. The mature intellect is identified by the person's possessing the capability of emotional self-management, wherein they can encounter, face, and resolve problems of life without being overwhelmed by emotion.[8]

Real-world experience is necessary to and for the development of a person's intellect, because, in resolving the problems of life, a person can intellectually comprehend a social circumstance (a time and a place) and so adjust their social behavior in order to act appropriately in the society of other people. Intellect develops when a person seeks an emotionally satisfactory solution to a problem; mental development occurs from the person's search for satisfactory solutions to the problems of life. Only experience of the real world can provide understanding of reality, which contributes to the person's intellectual development.[9]

Structure of intellect

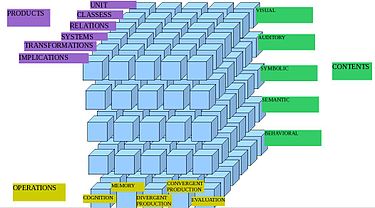

[edit]In 1955, the psychologist Joy Paul Guilford (1897–1987) proposed a Structural Intellect (SI) model in three dimensions: (i) Operations, (ii) Contents, and (iii) Products. Each parameter contains specific, discrete elements that are individually measured as autonomous units of the human mind.[10] Intellectual operations are represented by cognition and memory, production (by divergent thinking and convergent thinking), and evaluation. Contents are figurative and symbolic, semantic and behavioral. Products are in units, classes, and relations, systems, transformations, and implications.[11]

Intellect in psychotherapy

[edit]Intellectualization is a psychotherapeutic method based of intense intellectual focus in order to avoid dealing with a problem that occupies the attention of a person. In psychological praxis, intellectualization is a defense mechanism that blocks feelings in order to prevent anxiety and stress from acting upon and interfering with the psyche of the person, which otherwise would interfere with their normal functioning in real life. As psychotherapy, intellectualization is a rational, dispassionate, and scientific approach towards dealing with and resolving mental problems, which psychologically disturb the person.

The functions of intellectualization involve the Id, ego, and super-ego. The Ego is the conscious aspect of human personality; the Id is the unconscious, animal-instinct aspect; and the super-ego is the control mechanism that mediates and adjusts a person's thoughts and actions and behavior in accordance with the social norms of society. The purpose of intellectualization is to isolate the Id from the real world, and so make the conscious aspects of a person's life the only object of reflection and consideration. Therefore, intellectualization defends and protects the Ego from the Id, the unconscious aspect of human personality that usually is impossible to control.[12]

Socially, intellectualization uses technical jargon and complex scientific terminology instead of plain language; e.g. a physician uses the word carcinoma instead of cancer to lessen the negative impact of a diagnosis of terminal disease — by directing the patient's attention away from the bad news. The different registers of language, scientific (carcinoma) and plain language (cancer), facilitate the patient's acceptance of medical fact and medical treatment, by avoiding an outburst of negative emotions that would interfere with the successful treatment of the disease.[13]

Moreover, the defense mechanism of intellectualization is criticized because it separates and isolates the person from the painful emotions caused by the psychological problem. As such, the defense mechanism subsequently leads to the denial of intuition, which sometimes contributes to the processes of decision-making; a negative consequence of the absence of emotional stimuli can deprive the person of motivation, and lead to a mood of dissatisfaction, such as melancholy; such "emotional constipation" threatens their creativity, by replacing such capabilities with factual solutions.[14]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Corsini, Raymond J (2016). The Dictionary of Psychology. London: Routledge. p. 494. ISBN 9781317705710.

- ^ Colman, Andrew M. (2008). A Dictionary of Psychology (3rd ed.). Oxford [etc.]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191726828.

- ^ Davidson, Herbert (1992), Alfarabi, Avicenna, and Averroes, on Intellect, Oxford University Press page 6.

- ^ "Intellect and Intelligence". Psychology Today.

- ^ Sangha, Nithyananda. "Instinct, Intellect, Intelligence, Intuition". Nithyananda Sangha. Archived from the original on 23 July 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ^ Rowan, John. (1989) The Intellect. SAGE Social Science Collections, p. 000.

- ^ Bohm, David and Peat, F. David. Science, Order, and Creativity (1987) p.114.

- ^ VandenBos, Gary R. (2006). APA Dictionary of Psychology (1st ed.). Washington, DC.: American Psychological Association. ISBN 978-1-59147-380-0.

- ^ "Psychology of Knowledge: Development of the Intellect". augustinianparadigm.com. Retrieved 2015-11-01.

- ^ "Structure of Intellect (J.P. Guilford)". www.instructionaldesign.org. Retrieved 2015-10-28.

- ^ "Guilford's 'structure of intellect' model". homepages.which.net. Archived from the original on 2018-04-25. Retrieved 2015-11-02.

- ^ Lemouse, M. "Teaching Psychology — Defense Mechanisms". www.healthguidance.org. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- ^ Khetarpal, A. "Intellectualization: Isolation from Emotions! (A Psychological Tranquilizer) | Mindful Cogitations". abhakhetarpal.in. Archived from the original on 2015-07-07. Retrieved 2015-10-26.

- ^ "On Finding Out How We Don't Know Ourselves in Therapy and Counselling. (On Defences, Part Seven)". Lucid Psychotherapy & Counselling. 2015-05-19. Retrieved 2015-11-01.