Henry Drummond (evangelist)

Henry Drummond | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 17 August 1851 |

| Died | 11 March 1897 (aged 45) |

| Occupation | Evangelist, Biologist, Writer and Lecturer |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Notable works | The Greatest Thing in the World |

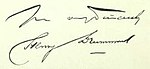

| Signature | |

| |

Henry Drummond FRSE FGS (17 August 1851 – 11 March 1897) was a Scottish evangelist, biologist, writer and lecturer.

Many of his writings were too adapted to the needs of his own day to justify the expectation that they would long survive it.[1] His sermon "The Greatest Thing in the World" remains popular in Christian circles.

Early life

[edit]Drummond was born at Park Place in Stirling, the son of William Drummond (d.1888) a seedsman and founder of Drummond Seeds, and his wife, Jane Campbell Blackwood (d.1910). His early education was at Stirling High School and Morrison's Academy.[2]

Drummond was educated at Edinburgh University, where he displayed a strong inclination for physical and mathematical science. The religious element was an even more powerful factor in his nature, and he entered the Free Church of Scotland. While preparing for the ministry, he became for a time deeply interested in the evangelizing mission of D.L. Moody and I.D. Sankey, where he was active for two years.[1] Theologically, Drummond was significantly influenced by the Reveil movement in Reformed Protestantism.[3]

Career

[edit]In 1877 he was lecturer on natural science in the Free Church College on Lynedoch Street in Glasgow, which enabled him to combine all the pursuits for which he felt a vocation.[4] Drummond advocated for theistic evolution.[5] His studies resulted in his writing Natural Law in the Spiritual World, the argument being that the scientific principle of continuity extends from the physical world to the spiritual. Before the book was published in 1883, an invitation from the African Lakes Company took Drummond to Central Africa.[1]

In 1880 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. His proposers were Sir Archibald Geikie, William Thomson, Lord Kelvin, John Gray McKendrick, and Sir Robert Christison.[2]

On his return in the following year he found himself famous. In 1884 he was a guest at Haddo House for a dinner hosted by John Hamilton-Gordon, 1st Marquess of Aberdeen and Temair in honour of William Ewart Gladstone on his tour of Scotland.[6] Large bodies of serious readers, among the religious and the scientific classes alike, discovered in Natural Law the common ground they needed; and the universality of the demand proved, if nothing more, the seasonableness of its publication. Drummond continued to be actively interested in missionary and other movements among the Free Church students.[1]

In 1888 he published Tropical Africa, a valuable digest of information.[7] In 1890 he travelled in Australia, and in 1893 delivered the Lowell Lectures in Boston. He had meant to keep them aside for mature revision, but an attempted piracy compelled him to hasten their publication, and they appeared in 1894 under the title of The Ascent of Man. Their object was to ratify altruism or, the disinterested care and compassion of animals for each other, important in effecting the survival of the fittest, a thesis previously maintained by philosopher professor John Fiske.[1]

Personal life

[edit]Drummond never married and had no children. In the late stage of his life he lived at 3 Park Circus in Glasgow.[8]

Death

[edit]Drummond's health failed shortly after The Ascent of Man.[1] He had suffered from bone cancer for some years, and he died on 11 March 1897 while travelling in Tunbridge Wells. His body was returned to Holy Rude Cemetery in Stirling for burial with his parents. The grave, marked by a large distinctive red granite Celtic cross, stands just north-east of the church.

In 1905 a medallion plaque to his memory was erected in the Free Church College in Edinburgh, sculpted by James Pittendrigh Macgillivray.

Selected writings

[edit]See Lennox's book for a fuller bibliography of Drummond's writings.[9]

- Natural Law in the Spiritual World (1883)

- Tropical Africa (1888)

- The Greatest Thing in the World: an Address (1890)

- The Greatest Thing in the World: and Other Addresses (1891)

- The Ascent of Man (1894)

- The Eternal Life (1896)

- The Ideal Life and Other Unpublished Addresses (1897)

- The Monkey That Would Not Kill (1898)

- The New Evangelism and Other Papers (1899)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Drummond, Henry". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 600.

- ^ a b Biographical index of former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN 0-902-198-84-X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 January 2013. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ Dromi, Shai M. (2020). Above the Fray: The Red Cross and the Making of the Humanitarian NGO Sector. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press. p. 43. ISBN 9780226680385.

- ^ Bebbington, David W. (1998). Henry Drummond, evangelicism and science. Scottish Church History Society. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- ^ Lightman, Bernard. (2010). Darwin and the Popularization of Evolution. Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London 64 (1): 5-24.

- ^ Emslie, Alfred Edward. "Dinner at Haddo House, 1884". National Portrait Gallery, London.

- ^ Review, Anti-Slavery Reporter, May–June 1888, p.82

- ^ Glasgow Post Office Directory 1895-96

- ^ * Lennox, Cuthbert (1901). The Practical Life Work of Henry Drummond. New York: James Pott and Company.

Further reading

[edit]- Smith, George Adam (1898). The Life of Henry Drummond. New York: Doubleday & McClure Company.

- Simpson, James Y. Henry Drummond. Edinburgh: Oliphant, Anderson and Ferrier, 1901, ("Famous Scots Series")

- Drummond, Henry (1884). Natural Law in the Spiritual World. Hodder and Stoughton (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2009; ISBN 978-1-108-00013-0)

- Drummond, Henry (1883). The Ascent of Man. J. Pott & Co. (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2009; ISBN 978-1-108-00053-6)

External links

[edit]- Works by Henry Drummond at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Henry Drummond at the Internet Archive

- Works by Henry Drummond at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- The Greatest Thing in the World by Henry Drummond on YouTube

- Zaremba narration of The Greatest Thing in the World

- The Monkey Who Would Not Kill with full text and full page images from the Baldwin Library of Historical Children's Literature

- Evangelicalism in Transition: A Comparative Analysis of the Work and Theology of D.L. Moody and His Proteges, Henry Drummond and R.A. Torrey,[permanent dead link] a Doctoral Dissertation by Mark James Toone, presented to the Faculty of St. Mary's College, University of St. Andrews, 1988

- 1851 births

- 1897 deaths

- 19th-century evangelicals

- British nature writers

- British religious writers

- Scottish Evangelical writers

- People associated with Glasgow

- People educated at Morrison's Academy

- People from Stirling

- Scottish evangelicals

- Scottish non-fiction writers

- Theistic evolutionists

- Scottish biologists

- Modern Christian devotional writers

- 19th-century ministers of the Free Church of Scotland

- 19th-century Scottish Presbyterian ministers