Action film

The action film is a film genre that predominantly features chase sequences, fights, shootouts, explosions, and stunt work. The specifics of what constitutes an action film has been in scholarly debate since the 1980s. While some scholars such as David Bordwell suggested they were films that favor spectacle to storytelling, others such as Geoff King stated they allow the scenes of spectacle to be attuned to story telling. Action films are often hybrid with other genres, mixing into various forms ranging to comedies, science fiction films, and horror films.

While the term "action film" or "action adventure film" has been used as early as the 1910s, the contemporary definition usually refers to a film that came with the arrival of New Hollywood and the rise of antiheros appearing in American films of the late 1960s and 1970s drawing from war films, crime films and Westerns. These genres were followed by what is referred to as the "classical period" in the 1980s. This was followed by the post-classical era where American action films were influenced by Hong Kong action cinema and the growing using of computer generated imagery in film. Following the September 11 attacks, a return to the early forms of the genre appeared in the wake of Kill Bill and The Expendables films.

Scott Higgins wrote in 2008 in Cinema Journal that action films are both one of the most popular and popularly derided of contemporary cinema genres, stating that "in mainstream discourse, the genre is regularly lambasted for favoring spectacle over finely tuned narrative."[2] Bordwell echoed this in his book, The Way Hollywood Tells It, writing that the reception to the genre as being "the emblem of what Hollywood does worst."[3]

Characteristics

[edit]In the Journal of Film and Video, Lennart Soberson stated that the action film genre has been a subject of scholarly debate since the 1980s.[4] Soberson wrote that repeated traits of the genre include chase sequences, fights, shootouts, explosions, and stunt work while other scholars asserted there were more underlying traits that define the genre.[4] David Bordwell in The Way Hollywood Tells It wrote that audiences are "told that spectacle over rides narrative" in action cinema while Wheeler Winston Dixon echoed that these films were typified by "excessive spectacle" as a "desperate attempt to mask the lack of content."[3][5] Geoff King argued that the spectacle can also be a vehicle for narrative, opposed to interfering with it.[6] Soberson stated that Harvey O'Brien had "perhaps the most convincing understanding of the genre", stating that the action film was "best understood as a fusion of form and content. It represents the idea and ethic of action through a form in which action, agitation and movement are paramount."[4]

O'Brien wrote further in his book Action Movies: The Cinema of Striking Back to suggest action films being unique and not just a series of action sequences, stating that that the difference between Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) and Die Hard (1988), that while both were mainstream Hollywood blockbusters with hero asserting masculinity and overcoming obstacles to a personal and social solution, John McClane in Die Hard repeatedly firing his automatic pistol while swinging from a high rise was not congruent with the image of Indiana Jones in Raiders swinging his whip to fend off villains in the backstreets of Cairo.[7] British author and academic Yvonne Tasker expanded on this topic, stating that action films have no clear and constant iconography or settings. In her book The Hollywood Action and Adventure Film (2015), she found that the most broadly consistent themes tend to be a characters quest from freedom from oppression such as a hero overcoming enemies or obstacles and physical conflicts or challenge, usually battling other humans or alien opponents.[8]

By late 2010s studies of genre analysis, the term "genre" itself is often replaced or supplemented with the words "mode" and "narrative form" with all three terms often being used interchangeably.[9] Johan Höglund and Agnieszka Soltysik Monnet said that the difference between these concepts are elusive, but stated that genre could be defined as belonging to specific historical and cultural moments while "mode" and "form" can refer to a larger pattern that operates across a wider historical and cultural field.[9] In their book Action Cinema Since 2000 (2024), Tasker, Lisa Purse, and Chris Holmlund stated that thinking of action as a mode is more helpful than thinking of it as a genre.[10] The three authors suggested that action frames a certain manner of filmmaking and viewing exceed genre without eclipsing it stating that websites such as IMDb and Wikipedia rarely label films by a single genre and that streaming services such as Amazon Prime and Netflix similarly dilutes what is marketed and received as action.[10]

History

[edit]| Action films |

|---|

|

| By decade |

In transnational cinema, there are two major trends in action films: Hollywood action films and their style being imitated around the globe and the other being Chinese-language martial arts films.[11] The roots of action films extend into the beginning of film but it was only in the mid-20th century when action films developed into their own recognizable genre instead of being a collection of other types of films such as Westerns, swashbucklers or adventure films.[1] Films have been described "action films" or "action-adventure film" as early as the 1910s.[4][12] Only by the 1980s was the term action as its own unique genre used routinely in terms of promotion and reviewing practices.[1]

Hong Kong action films

[edit]The first Chinese-language martial arts films can be traced to Shanghai cinema of the late 1920s. These films were popular during the period, which comprised almost 60% of the total Chinese films. Man-Fung Yip stated that these film were "rather tame" by contemporary standards.[13] He wrote that they lacked the kind of dazzling action choreography as expected today and had crude and rudimentary special effects.[13] These films came under increasing attack by both government officials and cultural elites for their allegedly superstitious and anarchistic tendencies, leading them to be banned in 1932. It was not until the base of Chinese commercial filmmaking was relocated from Shanghai to Hong Kong in the late 1940s that martial arts cinema was revived. These films contained much of the characteristics of the previous era. During this period, over 100 films were based on the adventures of real life Cantonese folk hero Wong Fei-hung who first appeared in film in 1949. These films primarily on circuited within Hong Kong and Cantonese-speaking areas with Chinese diaspora.[14] Yip continued that these Hong Kong films were still lagging behind in aesthetic and technical standards that films from the United States, Europe and Japan had during this period.[15]

Yip described Japanese cinema as the most advanced in Asia at the time. This was showcased by the international breakthrough of Akira Kurosawa's films like Rashomon (1950).[15] The film genre known as the chanbara was at its height in Japan. The style was a sub-genre to the jidai-geki, or period drama with an emphasis on sword fighting and action.[16] It had a similar level of popularity to that of the Western in the United States. The most internationally known films of this era were the films Kurosawa with Seven Samurai (1954), The Hidden Fortress (1958), and Yojimbo (1961).[17] By at least the 1950s, Japanese films were looked upon as a model to be emulated by Hong Kong film production, and Hong Kong film companies began actively enlisting professionals from Japan, such as cinematographer Tadashi Nishimoto to contribute to color and widescreen cinematography.[15] New literary sources also developed in martial arts films of this period, with the xinpai wuxia xiaoshuo (or "new school martial arts fiction") coming into prominence with the success of Liang Yusheng's Longhu Dou Jinghua (1954) and Jin Yong's Shujian enchou lu (1956) which showed influence of the Shanghai martial arts films but also circulated from Hong Kong to Taiwan and Chinese communities overseas. This led to a growing demand in both local and regional markets in the early 1960s and saw a surge in production of Hong Kong martial arts films that went beyond the stories about Wong Fei-hung which were declining in popularity.[18] These new martial arts films featured magical swordplay and higher production values and more sophisticated special effects than the previous films with Shaw Brothers a campaign of "new school" (xinpai) martial arts swordplay films such as Xu Zenghong's Temple of the Red Lotus (1965) and King Hu's Come Drink with Me (1966).[19]

In the 1970s, the Hong Kong martial arts films began to grow under the format of yanggang ("staunch masculinity") mostly through the films of Chang Cheh which were popular. This transition led to the kung fu film sub-genre at beginning of the decade and moved beyond the swordplay films with contemporary settings of late Qing or early Republican periods and had more hand-to-hand combat over supernatural swordplay and special effects.[21] A new studio, Golden Harvest quickly became one of independent filmmakers to grant creative freedom and pay and attracted new directors and actors, including Bruce Lee.[22] The popularity of kung fu films and Bruce Lee led to attract a global audience of these films in the United States and Europe, but was cut short on Lee's death in 1973 leading the phases popularity to decline.[20] Following a period of stagnation, Chang Cheh and Lau Kar-leung revitalized the genre with shaolin kung fu films and Chor Yuen's series of darker swordplay films based on the novels of Gu Long.[20] Kung Fu comedies appeared featuring Jackie Chan as martial arts films flourished into the 1980s. Other films again modernized the form with gangster films of John Woo (A Better Tomorrow (1986), The Killer (1989)) and the Wong Fei Hung saga returning in Tsui Hark's Once Upon a Time in China featuring Jet Li which again revitalized the swordplay styled films.[20] By the turn of the century Hollywood action films would look towards Hong Kong cinema and bringing some of their major actors and directors over to apply their style to their films, such as Chan, Woo, Li, Michelle Yeoh and Yuen Woo-Ping.[23] The release of Ang Lee's Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) led to a Global release status of Chinese-language martial arts films, most notably Zhang Yimou's Hero (2002) and House of Flying Daggers (2004), Stephen Chow's Kung Fu Hustle (2004) and Chen Kaige's The Promise (2005).[24] Most Hong Kong action films in the first quarter of the 21st century, such as those in Cold War (2012), Cold War 2 (2016) and The White Storm film series have their violence toned down, especially compared to the earlier work of directors like Woo and Johnnie To.[25] Antong Chen, in his study on the Hong Kong action film, wrote that the influence of China and the amount of Chinese co-productions made with Hong Kong created a shift in these films, particularly following the release of Infernal Affairs (2002).[26]

Hollywood action films

[edit]Harvey O'Brien wrote in 2012 that the contemporary action film emerged through other genres, primarily Westerns, crime and war films and can be separated into four forms: the formative, the classical, the postclassical and neoclassical phases.[27] Yvonne Tasker reiterated this in her book on action and adventure films, saying that action films became a distinct genre during the New Hollywood period of the 1970s.[8]

The formative films would be from the 1960s to the early 1980s where the Antihero appears in cinema, featuring characters who act and transcend the law and social conventions. This appears initially in films like Bullitt (1968) where a tough police officer protects society by upholding the law against systematic corruption. This extended into films which O'Brien described as "knee-jerk responses" to perceived threats with rogue cop and vigilante films such as Dirty Harry (1971) and Death Wish (1974) where the restoration of order is only possible by force and anti-social characters prepared to act when society does not.[27] The vigilantism reappears in other films that were exploitative of southern society such as Billy Jack (1971) and White Lightning (1973) and "good ol' boy" comedies like Smokey and the Bandit (1977). This era also emphasizes the car chase scenes as moments of spectacle in films like Bullitt and The French Connection (1971). O'Brien described these films as emphasizing "the fusion of man and machine" with the drivers and vehicles acting as one, concluding with what he described as "the ultimate in apocalyptic modernity and social erasure" in Mad Max 2 (1981).[28]

O'Brien described the classical form of action cinema to be the 1980s. The decade continued the trends of formative period with heroes as avengers (Lethal Weapon (1987)), rogue police officers (Die Hard (1988)) and mercenary warriors (Commando (1985)). Following the continuity of the car and man hybrid of the previous decade, the 1980s featured weaponized men with who were either also carrying weapons such as Sudden Impact (1983), trained to be weapons (American Ninja (1985)) or imbued with technology (RoboCop (1987)).[28] O'Brien noted that the formative trends at this point had become "identifiably generic" as film industries began to reproduced these films during the decade producers like Joel Silver and production companies like The Cannon Group, Inc. began to formulate production of these films with both high and low budgets.[29] The action films of this era have roots in classical story telling, specifically rooted from martial arts films and Westerns, and are built around a three-act structure centered on survival, resistance and revenge with narratives where the physical body of the hero is tested, traumatized and ultimately triumphant.[30]

The third shift in action cinema, the postclassical, was defined by the predominance of Eastern cinema and its aesthetics, primarily the wire-work of Hong Kong action cinema from the classical era, through the convention of the increasingly computer generated effects. This saw the decline of overt masculinity in the action film which corresponded with the end of the Cold War in 1991, while the rise of self-referential and parodies of this era grew in films like Last Action Hero (1993). O'Brien described this era as being soft where the hard bodies of the classical era were replaced with computer generated imagery such as that of Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991).[31] This was displayed in corresponding with corresponded with millennial angst and apocalypticism showcased in films like Independence Day (1996) and Armageddon (1998).[32] Action films of mass destruction began requiring more overtly super heroic characters with further comic book adaptations being made with increased non-realistic settings with films like The Matrix (1999).[33]

The fourth phase arrived following the September 11 attacks in 2001, which suggested an end to fantastical elements that defined the action hero and genre.[33] Following the release of Quentin Tarantino's Kill Bill: Volume 1 (2003) and Kill Bill: Volume 2 (2004) revisited the tropes of 1970s action films leading a renaissance of vengeance narratives in films like The Brave One (2007) and Taken (2008). O'Brien found that Tarantino's films were post-modern takes on the themes that rescinded irony to restore "cinephile re-actualization of the genre's conventions."[33] The genre went into full circle resurrecting films from the classical period with Live Free or Die Hard (2007) and Rambo (2008) finding the characters navigating a contemporary world while also acknowledging their age, culminating into The Expendables (2010) film.[33]

The most commercially successful action films and franchise of the 21st century have been comic book adaptations, which commenced with the X-Men and is seen in other series such as Spider-Man, and Iron Man series.[34][35] Tasker wrote that despite the central characters in superhero cinema being extraordinary, occasionally even God-like, they often followed the traces of the central character becoming powerful of which is fundamental to action films, often dealt with origin stories in superhero films.[36]

Subgenres

[edit]Hybrid genres

[edit]Action films often interface with other genres. Tasker wrote that films are often labelled action thrillers, action-fantasy and action-adventure films with different nuances.[37] Tasker later discussed that the term action film genre and adventure are often used in hybrid, and are even used interchangeably.[38] Along with Holmund and Purse, Tasker wrote that the action films expansiveness complicates easy categorization and though the genre is often spoken of as singular genre, it is rarely discussed as singular style.[39]

Screenwriter and academic Jule Selbo expanded on this, describing a film as "crime/action" or an "action/crime" or other hybrids was "only a semantic exercise" as both genres are important in the construction phase of the narrative.[40] Mark Bould in A Companion to Film Noir (2013) said that categorization of multiple generic genre labels was common in film reviews who are rarely concerned with succinct descriptions that evoke elements of the film's form, content and make no claims beyond on how these elements combine.[41][42]

Film Studies began to engage generic hybridity in the 1970s. James Monaco wrote in 1979 in American Film Now: The People, The Power, The Money, the Movies that "the lines that separate on genre from another have continued to disintegrate."[43] Tasker said that most post-classical action films are hybrids, drawing from genres as varied as war films, science fiction, horror, crime, martial arts and comedy films.[37]

Martial arts film

[edit]In Chinese-language films, both wuxia and kung fu are genre-specific terms, while martial arts is a generic term to refer to several types of films containing martial arts.[44]

Wuxia

[edit]The wuxia film is the oldest genre in Chinese cinema.[45] Stephen Teo wrote in his book on Wuxia that there is no satisfactory English translation of the term, with it often being identified as "the swordplay film" in critical studies. It is derived from the Chinese words wu denoting militarist or martial qualities and xia denoting chivalry, gallantry, and qualities of knighthood.[44] The term wuxia entered into popular culture in the serialization of Jinaghu qixia zhuan (1922) (transl. Legend of the Strange Swordsmen). [46] In wuxia, the emphasis is on chivalry and righteousness and allows for phantasmagoric actions over the kung fu film's more ground-based combat.[47]

Kung fu film

[edit]The Kung fu film emerged in the 1970s from the swordplay films.[48] Its name is derived from the Cantonese term gong fu which has two meanings: the physical effort required to completing a task and the abilities and skills acquired over time.[49] Films from the period reflected on the cultural and social climate from the period, as seen in invoking Japanese or Wester imperialist forces as foils.[48]

The kung fu film came out of the wuxia films.[44] In comparison to the wuxia, film, the focus on the kung fu film is on the martial arts over chivalry, [50] The martial arts films was in decline by the mid-1970s in Hong Kong in relation to the stock market crash which went from over 150 films in 1972 to just over 80 in 1975, which led to a downfall in martial arts films produced. When the economy became to rebound, a new trend of martial arts films, the Shaolin kung fu films emerged and sparked a revival of the genre.[51] Unlike the wuxia, the kung fu film primarily focuses on fighting on the ground.[47] While heroes in kung fu films often display chivalry, they generally hail from different fighting schools, namely wudang and shaolin.[44][47]

American-styled productions

[edit]American martial arts films feature what author M. Ray Lott described as a more realistic style of violence over the Hong Kong wuxia films with more realism and are often low-budget productions.[52] Martial arts began routinely appearing in fight scenes in American films in the 1960s with films like The Born Losers (1967) which was predominantly a drama, interspersed with martial arts scenes.[53][54] American martial arts films predominantly came into production following the release of Enter the Dragon (1973), with the only higher-budgeted American film to follow in its wake being The Yakuza (1974).[55][56] Lott noted the two films would lead to the two subsequent styles of martial arts films in the United States, with films like Enter the Dragon about people who reveled in combat, often in a tournament setting, and The Yakuza which had several genres attached to it, but featured several martial arts sequences.[57] By the end of the 1970s, the style was an established genre in American cinema, often featuring tough heroic characters who would fight and not think about their actions until after a fight sequence.[58] In the 1980s, American martial arts films reflected the national move towards conservatism, reflected in films of Chuck Norris and other actors such as Sho Kosugi.[59] The genre would shift from theatrical releases towards the end of the decade with the rise of home video, the lower box-office of American martial arts productions, and a significant portion of direct-to-video action films that first were made in the late 1980s in the United States were martial arts films.[55][59][60] Towards the end of the 1990s, production of low-budget marital arts films declined as no new stars in the genre developed and older actors such as Cynthia Rothrock and Steven Seagal started showing up in less and less films.[61][62] Even internationally popular films like Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) had negligible effects in American productions in either the direct-to-video field, or in similarly low-budgeted theatrical releases such as Bulletproof Monk (2003).[63]

While the American styled-films were predominantly made in the United States, productions were also made in Australia, Canada, Hong Kong and South Africa, and were predominantly shot in the English-language.[64]

Heroic bloodshed

[edit]Heroic Bloodshed is a that originates with English-language Hong Kong action and crime film fan communities in the late 1980s and early 1990s.[65] Author Bey Logan stated that the term was coined by Rick Baker, in the British fanzine Eastern Heroes.[65][66] The term is used broadly.[65] Baker described the style as Hong Kong action films which feature gangsters and gunplay and martial arts that were more violent than kung fu films and academic Kristof Van Den Troost described it a term used to distinguish Hong Kong gun-heavy action films from period martial arts films from the late 1980s and early 1990s.[66][65]

In the Chinese language, the term used for these films is jinghungpin, literally meaning "hero films".[65] Academic Laikwan Pang asserts that these gangster films appeared at a time when Hong Kong citizens felt particularly powerless with the handover of Hong Kong from the United Kingdom to China set for 1997.[67] The key directors of the genre were John Woo and Ringo Lam, and producer Tsui Hark, with the starting point of the genre being traced to Woo's A Better Tomorrow (1986) make a record-breaking HK$34.7 million at the Hong Kong box office.[68] The style of these films would influence American productions, such as Michael Bay's Bad Boys II (2003) and the Wachowskis' The Matrix (1999).[68] Korean media recognized the more fatalistic and pessimistic tone of these films, leading to Korean journalists to label the style as "Hong Kong noir".[69] The influence of these films was evident in early Korean films such as Im Kwon-taek's General's Son (1990) and later films such Song Hae-sung's A Better Tomorrow (2010), Cold Eyes (2013) and New World (2013).[70]

Postcolonial Hong Kong cinema has struggled to maintain its international identity as a provider of these types action films because the talents involved had abandoned the Hong Kong film industry after the handover in 1997.[71]

Regional action cinema

[edit]Anglophone action film scholarship has tended to emphasize bigger budget American action films, with academics tending to find films that fall out of Hollywood productions as not quite fitting definitions of the genre. By 2024, many national and regional industries were known for action films. These include international films such as Hindi, Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam, South Korean, Japanese, Thai, Brazilian, Chinese, South African, French and Italian action titles.[72]

Australia

[edit]At the turn of the millennium, Australian genre films have gained increasing acceptance in the Australian feature film industry, while the action genre represented a small percentage of its output in the 21st century.[73][74]

Scholars of Australian genre film generally used the term "action-adventure" which allows them to apply it to various forms of narratives such as tongue in cheek heroic posturing stories like Crocodile Dundee (1986), road movies or bush/outback films.[74] In the book Australian Genre Film, Amanda Howell suggested that this label was used to help distance Australian cinema from Hollywood films as it would be suggesting commerce over culture and that it would be "quite unacceptable to make Australian movies using conventions established in the U.S.A."[74] Howell stated this to be the case with action films of the 1970s and 1980s with Brian Trenchard-Smith's Turkey Shoot (1982) being the most notorious. Smith had previously released films like Deathcheaters (1976) and Stunt Rock (1979) when financial incentives were available for overtly commercial projects.[74] She commented that action films did tell identifiably Australian stories such as the Sandy Harbutt's biker film Stone (1974) and Miller's post-apocalyptic film Mad Max (1979) derived from Australia's social and cultural realities, as well as how George Miller's later Mad Max: Fury Road (2015) derived from Australia's long-standing cinematic fascination with the road and cars and a history of cultural anxiety towards a bleak and forbidding outback landscape opposed to the optimism of American action films.[74]

France

[edit]

France is a major European country for film production and has made co-production commitments with 44 countries around the world.[76] Around beginning of the 21st century, France began producing a series of films explicitly intended for international markets, with action films representing a significant portion. These films include Taxi 2 (2000), Kiss of the Dragon (2001), District 13 (2004) and Unleashed (2005).[77] Whan asked about the Americanization of these French films, Christophe Gans, director of Brotherhood of the Wolf (2001) stated that "Hollywood ownership of certain elements [...] must be challenged, in order to show that these elements have also long been present in European culture."[78]

The most significant producers of French action films with international ambitions is Luc Besson's France-based EuropaCorp, who released films like Taxi (1998) and From Paris with Love (2010).[75] EuropaCorp produced Transporter franchise starred British actor Jason Statham and made him an action film star, which led him to feature in The Expendables series by the end of the 2010s.[78]

India

[edit]The action film genre has been a staple of Bollywood cinema.[79] In the 1970s, the Bollywood action film consolidated with two films starring Amitabh Bachchan: Prakash Mehra's Zanjeer (1973) and Yash Chopra's Deewaar (1975). The box office success of these films made Bachchan a star and spawned the "angry young man" film in Bollywood cinema.[80] Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the action genre film declined considerably with new films predominantly featuring former body builders failing to reach the popularity Bachan had. These films predominantly earned their revenue through longer runs at B-grade theatres.[80] A cycle of action films came from these films in the 1980s and 1990s called the Avenging Woman film, where female protagonists seek justice for a rape victim, where the protagonist seeks revenge through violence.[81]

In 2009, the action genre was re-popularized with the box office success of Wanted (2009) starring Salman Khan. Khan reinvented his screen persona with that of his image in the Bollywood press who reported on him in the headlines of Bollywood magazines for his public brawls and affairs with leading actresses.[80] In Dabangg (2010), Khan continued with this public persona, which was repeated in several of his later films such as Ready (2011), Bodyguard (2011), Ek Tha Tiger (2012) and Dabangg 2 (2012).[82]

From the 1980s, generations of actors in Telugu cinema have invoked Hong Kong action films, such as Srihari who stated he wanted to become an actor after watching his first Bruce Lee film. Several films in Telugu cinema were remakes of Hong Kong films, such as Hello Brother (1994) which is based on Twin Dragons (1992).[83] Other films such as the martial arts film Bhadrachlam (2001), borrows from American cinema with the Jean-Claude Van Damme film Kickboxer (1989).[84] SS Rajamouli's RRR (2022) was among the highest budgeted films made in India, and became a rare hit film outside of Indian diaspora, where it broke box office records in Japan and performed exceptionally well in American box office.[85][86]

Japan

[edit]Japan was a difficult market for Hong Kong action cinema to break into. Prompted by the success of Enter the Dragon and the popularity of Bruce Lee, Toei made their own Bruce Lee-styled martial arts films, with The Street Fighter and its two sequels starring Sonny Chiba as well as a spin-off with a female lead similar to Hong Kong's Angela Mao called Sister Street Fighter. The success of Enter the Dragon briefly allowed an influx of Hong Kong films to Japan, but the trend did not last, with 28 Hong Kong films, mostly kung fu films, being released in 1974, and the number decreasing to five in 1975, four in 1977 and only two in 1978.[87]

Ryuhei Kitamura, director of Versus (2000), said in 2004 that he grew frustrated with the Japanese film industry as producers felt they couldn't make action films in competition with Hong Kong or American productions.[88] Versus grew to become popular outside of Japan, and Kitamura said he was aiming for the foreign audience, as he was disappointed with the current state of Japanese films.[89] Kitamura's characters have been described as "a careful combination of the maverick independence of 1980s Hollywood action heroes and the calmness and acceptance of Japanese samurai, a consistent criticism of Japanese people today."[90] Kitamura followed up Versus with two manga-inspired big-budget action films, Azumi and Sky High. Both released in 2003, the former was one of the highest-grossing movies of the year in Japan. Following LoveDeath, Kitamura's next directing work was in the United States.[91]

Korea

[edit]The action cinema of South Korea mostly existed on the margins of the film industry in South Korea.[92] The genre was initially called the Hwalkuk ("living theatre") was a term that indicated plays and films driven by action scenes, while this term has not been used regularly since the late 1970s, with "action movie" becoming the more familiar term.[93] The Korean action films came from Japanese cinema, James Bond series, and Hong Kong action cinema.[94] As North Korea borders China, it block access to the continent from a South Korean perspective, the Cold War allowed South Koreans to substitute deferred travel beyond the border through films with locations shot in Hong Kong.[95] While melodrama and comedy were stapples in South Korean cinema, most action films were sporadic and tied to the use of locations such as Hong Kong.[96] These films often featured one-legged or otherwise handicapped action characters similar to those of Japanese films (Zatoichi) and Hong Kong films (The One-Armed Swordsmen).[95][96] These included Im Kwon-taek's Returned Left-Handed Man (1968), Aekkunun Bak's One-Eyd Park (1970) and Lee Doo-yong's Returned One-Legged Man (1974).[97]

In the 1990s, the country's national cinema was in decline leading to Hong Kong gangster films filled in this void leading to large commercial success at the national box office.[98] Early Korean heirs to Hong Kong action films include Rules of The Game (1994), Beat (1997), and Green Fish (1997) involving men who gain confidence and achieve personal growth as they embark on journeys to protect national state and meet devastating ends.[99] South Korean cinema only received international attention in both art film and blockbuster formats towards the end of the 1990s. Films such as Chunhang (2000) and Memento Mori (2000) and action films Shiri (1999) and Nowhere to Hide (1999) received commercial releases in North America, Asia, and Europe. The success of the latter two films was unprecedented, and was followed by other South Korean action films in the early 2000s reaching the top of the local box office.[92] These South Korean films mimic some traits of the Hong Kong action cinema, such melodramatic male bonding and marginalized women characters, while the Korean films also have greater elements of tragedy and romance emphasized.[99]

Reception

[edit]Most martial arts films made before the mid-1960s were Cantonese-language productions. In comparison, Mandarin-language films were an integral part of Hong Kong cinema due to the influx of Shanghai film talent in the postwar period. These films were targeted at the more educated and more refined middle-class audiences who saw themselves as above the contemporary martial arts films.[14][15]

Scott Higgins wrote in 2008 in Cinema Journal that Hollywood action films are both one of the most popular and popularly derided of contemporary cinema genres, stating that "in mainstream discourse, the genre is regularly lambasted for favoring spectacle over finely tuned narrative."[2] Bordwell echoed this in his book, The Way Hollywood Tells It, writing that the reception to the genre as being "the emblem of what Hollywood does worst."[3]

Tasker wrote that when action and adventure films secured awards, it is often in categories such as visual effects and sound editing.[100]

Acclaimed action films

[edit]Time Out magazine conducted a poll with fifty experts in the field of action cinema, including actors, critics, filmmakers and stuntmen. Out of the 101 films ranked in the poll, the following films were voted the top ten best action films of all time.[101]

| Rank | Film | Year | Director | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Die Hard | 1988 | John McTiernan | United States |

| 2 | Aliens | 1986 | James Cameron | United States / United Kingdom |

| 3 | Seven Samurai | 1954 | Akira Kurosawa | Japan |

| 4 | The Wild Bunch | 1969 | Sam Peckinpah | United States |

| 5 | Police Story | 1985 | Jackie Chan | Hong Kong |

| 6 | Enter the Dragon | 1973 | Robert Clouse | Hong Kong / United States |

| 7 | Mad Max 2 | 1981 | George Miller | Australia |

| 8 | Hard Boiled | 1992 | John Woo | Hong Kong |

| 9 | Terminator 2: Judgment Day | 1991 | James Cameron | United States |

| 10 | Raiders of the Lost Ark | 1981 | Steven Spielberg | United States |

Gender in action cinema

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2024) |

Hong Kong

[edit]In Hong Kong, the "new school" of martial arts films that Shaw Brothers brought in 1965 featured what featured what Yip described as "strong, active female characters as protagonists." These female-centered films were challenged with the rise of a new male heroic prototype marked by a strong sense of youthful energy and defiance and by a propensity for violent action, identified with the films of Chang Cheh.[21]

Hollywood

[edit]Violent female characters have been part of cinema since its early inception, with characters such as Kate Kelly brandishing a shotgun in The Story of the Kelly Gang (1906). Women traditionally appear in action films as romantic interests, tomboys, or sidekicks to male protagonists.[102]

Violent white women would appear in other genres as well such as the femme fatales in film noir and horror films of the 1970s. Violent women were common in action films since the 1960s. These films featured working-class women exacting revenge. Films of the 1970s featured black women such as Pam Grier in films like Foxy Brown (1974).[102]

In the 1980s, a new symbolically transgressive character emerged in the form of Ellen Ripley in Aliens (1986) and Sarah Connor in Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) and the title character in China O'Brien (1990) who were physically muscular and or enacted more extreme violence that was usually reserve for male action leads.[102][103] In her book Contemporary Action Cinema (2011), Lisa Purse described the media response to female leads in action films reveal a discomfort about their presence and are often described with hesitant terms of women moving into territories that are perceived as masculine.[103] Revealing woman in this form deconstructs the notion that traditional marks of masculinity are not exclusive to men and that musculature was not natural, but something to be achieved. Accusations of these muscular women of the era were levelled at that them by 1993 were that they were "men in drag" and that the films generally have to "explain" why their female leads displayed physical aggression and why they were "driven to do it."[104] As the 1990s went on, Hollywood films began having more conventional looking women in their action films such as The Long Kiss Goodnight (1996).[105]

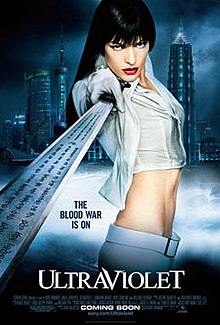

A vibrant debate exists about whether hypersexualization is itself empowering and, if not, whether a hypersexualized female character can still represent strength and autonomy.[102] Hypersexualized female action leads had tight fitting or revealing costumes that Tasker identified as "exaggerated statements of sexuality" and in the tradition of "fetishistic figure of fantasy" derives from comic books and soft pornography.[106] This originated in television with characters like Buffy Summers (Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997–2003)) and Xena (Xena: Warrior Princess (1995–2001)). These series popularity demonstrated a growing market for female action film heroes, in films of the 2000s like Lara Croft: Tomb Raider (2001), Charlie's Angels (2000), Ultraviolet (2006), Salt (2010) and series like Underworld and Resident Evil. These series like their television series earlier, had their leads eroticized as active and physically capable while also being scantily-clad, hyper-feminized similar to the woman of exploitation films of the 1970s such as Caged Heat (1974) and Big Bad Mama (1974).[107] While characters like Frank in The Transporter series are permitted to visibly sweat, strain and be bloodied, Purse found a reluctance for filmmakers to have their female leads have any appearance warping injuries to ensure a perfectly made-up face.[108] Comedy is often used in films of this period to place the female leads in implausible elements, such as in Charlie's Angels, Fantastic Four (2005) and My Super Ex-Girlfriend (2006).[109] The fighting styles of women also tend towards more traditionally feminine fluid movements of martial arts, over using guns or directly punching.[110]

Purse wrote that the contemporary female action film lead's sexualized brand had her in close proximity of post-feminism discourse about choice, power and sexuality.[110] Marc O'Day interprets the action heroine's dual status of an active subject and sexual object was overturning the traditional gender binary because the films "assume that women are powerful" without resorting to justify her physical aggression through narratives involving maternal drive, mental instability or trauma.[111] Purse found that female leads in films like Elektra (2005), Kill Bill, Underworld, Charlie's Angels and Mr. & Mrs. Smith (2005) did showcase women having expensive cars, clothing, travel, homes and often high-paying jobs, but that this was only shown as being applicable to white middle-class women.[112] Purse found that these women were empowered at the price of women of other ethnicities. This is seen in Aeon Flux (2005) where Sithandra dies protecting Aeon and Rain's death to make way for Alice in Resident Evil (2002).[112]

See also

[edit]- List of action film actors

- List of action film directors

- List of female action heroes and villains

- Action hero

- Film genre

- Lists of action films

- List of female action heroes

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Kendrick 2019, p. 36.

- ^ a b Higgins 2008, p. 74.

- ^ a b c Bordwell 2006, p. 104.

- ^ a b c d Soberson 2021, p. 19.

- ^ Dixon 2000, p. 4.

- ^ King 2000, p. 4.

- ^ O'Brien 2012, p. 6.

- ^ a b Tasker 2015, p. 2.

- ^ a b Höglund & Soltysik Monnet 2018, p. 1302.

- ^ a b Holmlund, Purse & Tasker 2024, p. 1.

- ^ Yip 2017, p. 147.

- ^ Willemen 2005, p. 226.

- ^ a b Yip 2017, p. 4.

- ^ a b Yip 2017, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d Yip 2017, p. 157.

- ^ Sharpe 2011, p. 43.

- ^ Sharpe 2011, p. 44.

- ^ Yip 2017, pp. 6.

- ^ Yip 2017, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b c d Yip 2017, pp. 8.

- ^ a b Yip 2017, pp. 7.

- ^ Yip 2017, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Yip 2017, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Yip 2017, pp. 9.

- ^ Chen 2022, p. 118.

- ^ Chen 2022, p. 120.

- ^ a b O'Brien 2012, p. 12.

- ^ a b O'Brien 2012, p. 13.

- ^ O'Brien 2012, pp. 13–14.

- ^ O'Brien 2012, p. 14.

- ^ O'Brien 2012, p. 15.

- ^ O'Brien 2012, p. 15-16.

- ^ a b c d O'Brien 2012, p. 16.

- ^ Tasker 2015, p. 179.

- ^ Tasker 2015, p. 182.

- ^ Tasker 2015, p. 180.

- ^ a b Tasker 2004, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Tasker 2015, p. 17.

- ^ Holmlund, Purse & Tasker 2024, p. 2.

- ^ Selbo 2014, pp. 229–232.

- ^ Bould 2013, p. 34.

- ^ Bould 2013, p. 44.

- ^ Monaco 1979, p. 56.

- ^ a b c d Teo 2016, p. 2.

- ^ Teo 2016, p. 1.

- ^ Teo 2016, p. 3.

- ^ a b c Teo 2016, p. 4.

- ^ a b Yip 2017, p. 26.

- ^ Yip 2017, p. 48.

- ^ Teo 2016, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Yip 2017, p. 49.

- ^ Lott 2004, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Lott 2004, p. 28.

- ^ Lott 2004, p. 42.

- ^ a b Lott 2004, p. 1.

- ^ Lott 2004, p. 15.

- ^ Lott 2004, p. 19.

- ^ Lott 2004, p. 67.

- ^ a b Lott 2004, p. 69.

- ^ Lott 2004, p. 101.

- ^ Lott 2004, p. 199.

- ^ Lott 2004, p. 200.

- ^ Lott 2004, p. 206.

- ^ Lott 2004, p. 8.

- ^ a b c d e Van Den Troost 2024, p. 234.

- ^ a b Logan 1995, p. 126.

- ^ Pang 2005, pp. 35–37.

- ^ a b Bitel 2019.

- ^ Kelso-Marsh 2020, p. 59.

- ^ Kelso-Marsh 2020, p. 60.

- ^ Martin 2009, p. 31.

- ^ Holmlund, Purse & Tasker 2024, p. 3.

- ^ Ryan & McWilliam 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Howell 2021.

- ^ a b Purse 2011, pp. 173–174.

- ^ Purse 2011, pp. 172–173.

- ^ Purse 2011, p. 173.

- ^ a b Purse 2011, p. 174.

- ^ Shandilya 2024, p. 163.

- ^ a b c Shandilya 2014, p. 112.

- ^ Shandilya 2024, pp. 163–164.

- ^ Shandilya 2014, p. 113.

- ^ Srinivas 2005, p. 112.

- ^ Srinivas 2005, p. 112-113.

- ^ BBC 2023.

- ^ Abrams 2022.

- ^ Yip 2017, p. 166.

- ^ Directory of World Cinema: Japan 3 2015, p. 77.

- ^ Mes 2004.

- ^ Directory of World Cinema: Japan 3 2015, p. 78.

- ^ Macias 2008.

- ^ a b Soyoung 2005, p. 97.

- ^ Soyoung 2005, p. 100.

- ^ Soyoung 2005, p. 101.

- ^ a b Soyoung 2005, p. 99.

- ^ a b Soyoung 2005, p. 103.

- ^ Yip 2017, p. 170.

- ^ Choi 2011.

- ^ a b Kwon 2023.

- ^ Tasker 2015, p. 8.

- ^ Rothkopf, Joshua; Semlyen, Phil (21 March 2022). "The 101 Best Action Movies of All Time". Time Out. Time Out Group. Archived from the original on 2020-08-28. Retrieved 2022-05-17.

- ^ a b c d Heldman, Frankel & Holmes 2016.

- ^ a b Purse 2011, p. 76.

- ^ Purse 2011, p. 77.

- ^ Purse 2011, p. 78.

- ^ a b Purse 2011, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Purse 2011, p. 79.

- ^ Purse 2011, p. 81.

- ^ Purse 2011, p. 80.

- ^ a b Purse 2011, p. 82.

- ^ O'Day 2004, p. 215.

- ^ a b Purse 2011, pp. 82–83.

Sources

[edit]- Directory of World Cinema: Japan 3. Intellect Books. 2015. ISBN 978-1-78320-403-8.

- Abrams, Simon (August 3, 2022). "How the Indian Action Spectacular 'RRR' Became a Smash in America". The New York Times. Retrieved January 25, 2024.

- Arroyo, Jose (2000). Action/Spectacle Cinema: A Sight and Sound Reader. British Film Institute. ISBN 0-85170-757-2.

- "Oscar Nominee RRR: Why the Indian Action Spectacle is Charming the West". BBC. January 24, 2023. Retrieved January 25, 2024.

- Bitel, Anton (July 10, 2019). "Heroic Bloodshed: How Hong Kong's Style Was Swiped By Hollywood". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on August 31, 2021. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

- Bordwell, David (2006). The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520246225.

- Bould, Mark (2013). "Genre, Hybridity, Heterogeneity or the Noir-SF-Vampire-Zombie-Splatter-Romance-Comedy-Action-Thriller Problem". In Spicer, A.; Hanson, H (eds.). A Companion to Film Noir. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. ISBN 9781444336276.

- Chen, Antong (2022). "Hong Kong Action Films' Aesthetics of Violence: Its Social Environment and Decline in the 21st Century". Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research. 638.

- Choi, Jinhee (2011). The South Korean Film Renaissance. Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 978-0819569868.

- Dixon, Wheeler W. (2000). Film Genre 2000:New Critical Essays. State University of New York Press. ISBN 0791492958.

- Heldman, Caroline; Frankel, Laura Lazarus; Holmes, Jennifer (2016). ""Hot, Black Leather, Whip": The (De)evolution of Female Protagonists in Action Cinema, 1960–2014". Sexualization, Media, & Society. doi:10.1177/2374623815627789.

- Higgins, Scott (Winter 2008). "Suspenseful Situations: Melodramatic Narrative and the Contemporary Action Film". Cinema Journal. 48 (2).

- Höglund, Johan; Soltysik Monnet, Agnieszka (December 2018). "Revisiting Adventure: Special Issue Introduction". Journal of Popular Culture. 51 (6): 1299–1311. doi:10.1111/jpcu.12747. ISSN 0022-3840.

- Holmlund, Chris; Purse, Lisa; Tasker, Yvonne (2024). "Introduction: Action as Mode". In Holmlund, Chris; Purse, Lisa; Tasker, Yvonne (eds.). Action Cinema Since 2000. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781839022784.

- Howell, Amanda (2021). "The Action Genre and the 'International Turn' in Australian Cinema". Australian Genre Film. Routledge. ISBN 9780429469121.

- Jones, Nick (2015). Hollywood Action Films and Spatial Theory. Routledge. ISBN 9781138057050.

- Kelso-Marsh, Caleb (2020). "East Asian Noir: Transnational Film Noir in Japan, Korea and Hong Kong". In Feng, Lin; Aston, James (eds.). Renegotiating Film Genres in East Asian Cinemas and Beyond. Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 978-3-030-55076-9.

- Kendrick, James (2019). "A Genre of Its Own: From Westerns, to Vigilantes, to Pure Action". In Kendric, James (ed.). A Companion to the Action Film. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1119100492.

- King, Geoff (2000). Spectacular Narratives: Hollywood in the Age of the Blockbuster. IB Tauris. ISBN 9781860645730.

- Kwon, Jungmin (April 2023). ""Hey 'Brother', You Can Count on Me": Misogynistic Masculinity and Bromance Genre in South Korean Action Cinema". The Journal of Popular Culture. 56 (2): 302–323. doi:10.1111/jpcu.13188. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- Logan, Bey (1995). Hong Kong Action Cinema. The Overlook Press. ISBN 0-87951-663-1.

- Lott, M. Ray (2004). The American Martial Arts Film. McFarland & Company, Inc. ISBN 0-7864-1836-2.

- Macias, Patrick (January 30, 2008). "Ryuhei Kitamura Interview: Directing with Napalm". Otaku USA. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- Martin, Daniel (2009). "Another Week, Another Johnnie To Film: The Marketing and Distribution of Postcolonial Hong Kong Action Cinema". Film International. Vol. 7, no. 4. ISSN 1651-6826.

- Monaco, James (1979). American Film Now: The People, The Power, The Money, the Movies. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195025709.

- Mes, Tom (May 17, 2004). "Ryuhei Kitamura". Midnight Eye. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- O'Brien, Harvey (2012). Action Movies: The Cinema of Striking Back. Wallflower Press. ISBN 978-0-231-16331-6.

- O'Day, Marc (2004). "Beauty in Motion: Gender, Spectacle and Action Babe Cinema". In Tasker, Yvonne (ed.). The Action and Adventure Cinema. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415235075.

- Pang, Laikwan (2005). "Post-1997 Hong Kong Masculinity". In Pang, Laikwan; Wong, Day (eds.). Masculinities and Hong Kong Cinema. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 962-209-737-5.

- Purse, Lisa (2011). Contemporary Action Cinema. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-3817-8.

- Ryan, Mark David; McWilliam, Kelly (2021). Australian Genre Film. Routledge. ISBN 9780429469121.

- Selbo, Jule (2014). Film Genre for the Screenwriter. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-69568-4.

- Shandilya, Krupa (2014). "Of Enraged Shirts, Gyrating Gangsters and Farting Bullets: Salman Khan and the New Bollywood Action Film". South Asian Popular Culture. 12 (2): 111–121. doi:10.1080/14746689.2014.937579. S2CID 144426047.

- Shandilya, Krupa (2024). "Bollywood's New Action Cinema: The Woman-led Action Film and the Nation". In Holmlund, Chris; Purse, Lisa; Tasker, Yvonne (eds.). Action Cinema Since 2000. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781839022784.

- Sharpe, Jasper (2011). Historical Dictionary of Japanese Cinema. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7541-8.

- Soberson, Lennart (Spring 2021). "The Ultimate Ride: A Comparative Narrative Analysis of Action Sequences in 1980s and Contemporary Hollywood Action Cinema". Journal of Film and Video. 73 (1).

- Soyoung, Kim (2005). "Genre as Contact Zone: Hong Kong Action and Korean Hwalkuk". In Morris, Meaghan; Li, Siu Leung; Ching-kiu, Stephen Chan (eds.). Hong Kong Connections: Transnational Imagination in Action Cinema. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 1-932643-19-2.

- Srinivas, S.V. (2005). "Hong Kong Action Film and the Career of the Telugu Mass Hero". In Morris, Meaghan; Li, Siu Leung; Ching-kiu, Stephen Chan (eds.). Hong Kong Connections: Transnational Imagination in Action Cinema. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 1-932643-19-2.

- Tasker, Yvonne, ed. (2004). Action and Adventure Cinema. Routledge. ISBN 0-203-64515-4.

- Tasker, Yvonne (2015). The Hollywood Action and Adventure Film. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 978-0-470-65924-3.

- Teo, Stephen (2016). Chinese Martial Arts Cinema: The Wuxia Tradition (2 ed.). Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-1-4744-0386-3.

- Van Den Troost, Kristof (Summer 2024). "Registers of the Melodramatic Mode: The 1980s Heroic Bloodshed Cycle in the History of the Hong Kong Crime Film". Screen. 65 (2). ISSN 0036-9543.

- Willemen, Paul (2005). "Action Cinema, Labour Power and the Video Market". In Morris, Meaghan; Li, Siu Leung; Ching-kiu, Stephen Chan (eds.). Hong Kong Connections: Transnational Imagination in Action Cinema. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 1-932643-19-2.

- Yip, Man-Fung (2017). Martial Arts Cinema and Hong Kong Modernity. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 978-988-8390-71-7.

Further reading

[edit]- Inness, Sherrie, ed. (2004). Action chicks: new images of tough women in popular culture. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-6396-3.

- Kim, L.S. (Winter 2006). "Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon: making women warriors – a transnational reading of Asian female action heroes". Jump Cut:A Review of Contemporary Media. 48.

- Osgerby, Bill; Gough-Yates, Anna; Wells, Marianne (2001). Action TV: tough guys, smooth operators and foxy chicks. London New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-22621-9.

- Tasker, Yvonne (2002). Spectacular bodies: gender, genre, and the action cinema. London New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-22184-6.

External links

[edit]- Taylor, John (April 1, 1991). "Hollywood's New Action Toys". New York Magazine. Retrieved 2010-12-01.